![]()

Part I

Statecraft

![]()

INTRODUCTION

Carolyn Gallaher

The first set of concepts considered in Key Concepts in Political Geography concern statecraft. The state is one of political geography’s central units of analysis. Political geographers ask and answer a lot of questions about states. Some geographers focus on how states are formed and governed. Others analyse how state power is established, legitimized and resisted in the world system. Still others examine specific forms of state organization.

In this part of the book four concepts related to statecraft are considered. The first, the nation-state, is a central theme in geographic research. Geographers have long noted, for example, that nations – with the nation defined broadly as a group that sees itself linked by history, language and/or culture – do not always match the administrative boundaries of modern states. The nation-state is as much an ideal type as it is a realized entity in most places. Geographers have been at the forefront of examining the tensions that arise in places where national and state boundaries do not match.

The second concept discussed here is sovereignty. Geographers are interested in sovereignty because the concept encapsulates how a state gains and holds authority over the people living within its boundaries and the activities they engage in. The idea behind state sovereignty – that states are the only legitimate actors on the world stage – underpins the world system and the international laws designed to govern it. However, as geographers also note, globalization has undermined the durability of this view and some even suggest that the era of state sovereignty may end.

In the final two chapters here we examine statecraft more narrowly. Chapter 3 on governance examines the mechanisms by which a government accumulates capital and regulates the social polity. While states are meant to represent the interests of their citizens, at times citizens will contest the mechanisms by which they are governed. As such, geographers study not only how governance structures are organized, but also how they vary across social and geographic divides. In Chapter 4, a particular type of government structure – democracy – is considered. Although democracy is often held out as an ideal form of government, especially by western powers, geographers note that there is no universal definition of democracy. Governments can and do use a variety of mechanisms for ensuring some form of popular representation in government. And, each has its benefits and its disadvantages.

To get a feel for these concepts case studies are provided from across the globe, including South Africa, Mexico and the US.

![]()

1 NATION-STATE

Mary Gilmartin

Definition: A Concept’s Two Parts

The term ‘nation-state’ is an amalgam of two linked though different concepts, nation and state. Nations are usually described as groups of people who believe themselves to be linked together in some way, based on a shared history, language, religion, other cultural practices or links to a particular place. States are usually defined as legal and political entities, with power over the people living inside their borders. In this way, states are associated with territorial sovereignty. The concept of a nation-state fuses together the nation – the community – and the state – the territory. In doing so, it provides us with a key unit of socio-spatial organization in the contemporary world. In defining the nation-state, it is important to consider its two separate components as well as the relationship between nation and state. A nation, according to Anthony Smith, is a named human population ‘sharing an historic territory, common myths and historical memories, a mass, public culture, a common economy and common legal rights and duties for all members’ (in Jones et al. 2004b: 83). Smith’s definition points to a number of commonalities, around territory, culture, history and memory, which may suggest that there is an essential quality to a nation. An essentialist understanding of a nation (sometimes called primordialism) suggests that it has always existed, and that it has an unchanging core.

An essentialist view of the nation is strongly contested by those who see nations as socially constructed. For example, Benedict Anderson famously argued that nations are imagined communities, because ‘the members of even the smallest nation will never know their fellow members, meet them or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each they carry the image of their communion’ (Anderson 1983: 15–16). Nations, in this way of thinking, come into being to serve particular purposes, often economic or political (Storey 2001: 55). This approach to nation formation may either be perennialist or modernist (the modern era is usually defined as beginning with the industrial revolution). A perennialist theory of nation formation suggests that the nation is rooted in pre-modern ethnic communities. In contrast, a modernist theory of nation formation suggests that processes associated with the modernist period – such as the development of states, the advent of mass literacy and education, or the spread of capitalism – led to the creation of nations.

The second component of the concept of the nation-state is the state. John Rennie Short observed that one of the most important developments of the twentieth century was ‘the growth of the state’ (Short 1993: 71). Short commented both on the increase in the number of states, from about 70 in 1930 to over 190 in 2007, and on the growth of state power. The increase in this period in the number of states is closely linked to decolonization. As empires were dissolved, particularly after World War II, imperial spatial organization (where territories were governed from the centre of the Empire, for example London) was replaced, to a large extent, with a state-based system of spatial organization. Many of these new states were based on European models, with a strong emphasis on territoriality and on the management of people and resources. Contemporary states have power and influence over both internal and external relations. Internally, the state works to gather revenue, maintain law and order and to support the ideology of the state. Externally, the state works to defend its borders and territory and to maintain favourable political and economic relations (Jones et al. 2004; Short 1993: 71) (see Figure 1.1).

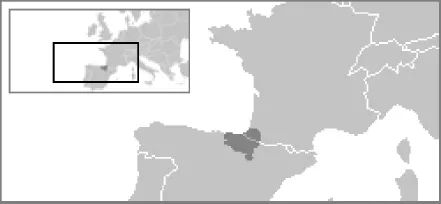

The nation-state is an ideal type: it suggests that the borders of the nation and the borders of the state coincide, so that every member of a nation is also a member of the same state, and every member of a state belongs to the same nation. In practice, this is impossible to achieve. The result is a variety of combinations of nation and state. One combination is states which contain many nations, such as Spain, with minority nations such as Basque and Catalan (see Figure 1.2). Another is nations spread across more than one state, such as the Irish nation in the Republic of Ireland and also Northern Ireland (part of the United Kingdom). A third combination is that of nations without states: the Basque nation may be defined in this way, as may the Kurdish nation, living in Turkey, Syria, Iran and Iraq.

There are clear disagreements over how a nation-state comes into being. However, these disagreements do not extend to the influence of the concept and its ability to galvanize people into action. This happens through nationalism, described by Anthony Smith as ‘an ideological movement for attaining and maintaining autonomy, unity and identity on behalf of a population deemed by some of its members to constitute an actual or potential nation’ (in Storey 2001: 66; for more detail see Chapter 23). Smith suggests that there is a distinction between ethnic and civic nationalism, where ethnic nationalism focuses on shared ethnic identification and commonalities, while civic nationalism focuses on shared institutions. The distinction between ethnic and civic nationalism suggested by Smith creates a hierarchy of nationalisms. This has implications for how nations and states are understood, with the creation of categories of ‘failed’ (and, by association, successful) states in the contemporary world.

Figure 1.1 A fortified portion of the border between Mexico and the US

Figure 1.2 Map of Basque provinces in Spain and France

Despite their obvious differences, the terms nation, state and nation-state are often used interchangeably. It is important to acknowledge this slippage. For example, much work in political geography highlighted the state, but was based on an implicit assumption that the state was also a nation – in other words, that its population shared a particular national identity. As such, the term ‘state’ implied national cohesion, but often served to mask conflict at subnational levels: between ethnic or racial groups, between regions, or around issues of power or ideology. In a similar vein, the use of the term state implied a form of civic nationalism, which again served to reinforce global hierarchies, even though the territory may well have been in the process of ethnic nation-building. The politics of naming is significant, and the assumptions underpinning the categorizations of nation, state and nation-state should always be interrogated.

Evolution and Debate: Is the Nation-state Relevant Any More?

The nation-state is one of the building blocks of political geography. Early political geographers, such as Friedrich Ratzel and Halford Mackinder, paid particular attention to the nation-state: Ratzel in his conceptualization of the state as a living organism that needed to grow in order to survive; Mackinder through his articulation of the state as a place where social and political goals could be pursued (Agnew 2002: 63–70). The state remained at the centre of political geography, so much so that Peter Taylor has argued that the focus on the state as a spatial entity distinct from social conflict led to an innate conservatism in the discipline (2003: 47). In other words, political geographers were so concerned with privileging the state as an entity that they failed to adequately investigate the state as a site of contestation, for example between different ethnic groups living in the state.

This lack of attention to contestation within the nation-state has been addressed in recent years, particularly through a greater concern with questions of identity. On one level, this has been addressed through a focus on the process of nation-building, with particular attention to monumental, memorial and other symbolic landscapes (see Johnston 1995 and Whelan 2003 for a discussion of this process in Ireland). In recent years, political geographers have also been more attentive to questions of gender, race, ethnicity, class and sexuality, highlighting ongoing contestations over the definition of the nation-state, as well as challenges to the processes of exclusion that underpin national identities. For example, feminist political geographers have highlighted the gendered nature of nation-states and national identity and have argued for a deeper engagement with the ways in which feminized and apparently private spaces, such as the household, are central to how nation-states are imagined and work (see Staeheli et al. 2004). Similarly, recent work on sexuality within political geography has highlighted the ways in which nation-states are often heteronormative, with national identities constructed around an assumed heterosexuality. This attention to identity has most recently been articulated in relation to citizenship (for example, see the discussion of sexual citizenship in Political Geography 25: 8, which attempts to move the concept of citizenship beyond the political, and argues that sexuality is part of citizenship). The concept of citizenship, particularly in relation to individuated rights and responsibilities, has been the focus of much recent research on states within political geography. (See Chapter 24 for a more detailed discussion.) Postcolonial theory has been used by geographers to question the exclusionary practices of nation-states after colonialism. (See Chapter 25 for a more detailed discussion.) In addition to highlighting debates about processes of inclusion and exclusion and resulting conflicts within the boundaries of the nation-state, political geographers have also started to engage more broadly with questions of governance within the nation-state. This has included a focus on local scales, such as the changing forms and functions of local states in a globalizing and neoliberal world (see Jones et al., 2004b Chapter 4, for an overview). This has also included a focus on protest and resistance movements, as well as the state’s responses to such movements (see Herbert 2007).

More fundamentally, however, the nature and existence of the nation-state has itself come under scrutiny. For some commentators, the nation-state is an anachronism, superseded by supranational organizations such as the United Nations and the European Union, and by processes such as globalization. John Agnew has suggested that ‘the modern territorial state is now is question in ways that would have been unthinkable even twenty years ago’ (2002: 112). Agnew highlights globalization, global migration, the collapse of the ‘strong states’ of the Soviet Union, the growth of supraregional and global forms of governance and the increase in ethnic and regional conflicts within states to support his assertion. The relationship between the nation-state and globalization has received particular attention. One school of thought is encapsulated in Kenichi Ohmae’s comment that ‘traditional nation-states have become unnatural, even impossible business units in a global economy’ (in Jones et al. 2004b: 51). In contrast, others suggest that the nation-state remains important despite globalization (see Yeung 1998). Similar ambivalence is evident in discussions of global migration, with some arguing that the so-called ‘age of migration’ has led to significant numbers of transnational migrants, who maintain strong networks and links with their countries of origin as well as their places of residence. Their presence and their activities, it is suggested, challenge state and national borders and ideologies (see Nagel 2001 for an overview). Other commentators suggest, however, that the scale of global migration has led to a tightening up of state immigration policy and an intensification of border controls and surveillance. This ambivalence is also present in discussions of global terrorism and global social movements, and in debates over the extent to which states can or cannot, as the case may be, contain and control terrorist or protest activities within their borders. This has suggested the concept of a failed state, described by some commentators as a state that is incapable of asserting authority within its own borders, but seen by other commentators as a neocolonial concept applied primarily to former colonies. In short, the nation-state in the contemporary world is, despite its ubiquity, a contested concept, and political geographers are central to debates over its contested meanings.

Case Study: South Africa after Apartheid

South Africa provides an interesting site for the study of the nation-state. During the apartheid era in South Africa, the population of the country was divided on racial and ethnic lines into separate territories. Under apartheid, South Africa was clearly not a nation-state, but consisted of a number of nations – racially and ethnically defined – within one state. Those nations were socially constructed. As an example, Crampton has written of the importance of the Voortrekker Monument in Pretoria in articulating a nationalist Afrikaner identity in the 1940s (Crampton 2001). The Voortrekker Monument was intended to celebrate the Great Trek of Afrikaners into the interior of South Africa in the 1840s, and Crampton considers the inauguration of the monument in 1949 as part of a broader Afrikaner national...