- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Self-Leadership and Personal Resilience in Health and Social Care

About this book

This is essential reading for professionals making judgements under pressure. It demonstrates how self-leadership is not only about surviving but thriving in a continually changing environment and introduces key theories, skills and debates to help professionals deliver high quality professional practice every day. The book focuses in on the quality of professional thinking, self- and social awareness, self-regulation and self-management, and the fundamentals of sustained resilience.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Chapter 1 Leadership Theories

Introduction

This chapter examines some of the most popular leadership theories in history, presenting the advantages, disadvantages and criticisms of each and the reported research. It starts to build the case for why self-leadership works in the current context of the public sector and, in particular, Health and Social Care.

Some authors conceptualise leadership as a set of traits, the personality of the leader and their behaviours, whereas others see it as an ability to manage the situation, or from a relationship standpoint, transforming or serving others. Northouse (2013) defines leadership as a ‘process whereby an individual influences a group of individuals to achieve a common goal’. This focus away from a distinctive preoccupation with the importance of traits and characteristics to an ‘event … between the leader and the followers’, is an interactive process consisting of observable behaviours that Northouse (2013) argues can be learnt.

This is one explanation; throughout history there have been many different leadership theories, with each losing its initial popularity as the latest approach fails to meet expectations, or exceptions to the theory became more apparent. Examining these influences and perspectives on leadership before discussing self-leadership provides not only the historical background, but a case to support self-leadership as a fundamental approach. Before examining these theories it is important to address two linked concepts: management and leadership.

Management versus Leadership

Key distinctions between management and leadership were reinforced by Bennis and Nanus's (1985, p221) statement that managers ‘do things right’, and ‘leaders do the right thing’. This distinction artificially intimated that leadership was more important, and in some way better, although there is a considerable amount of interplay between the two concepts of management and leadership. Making arbitrary distinctions between the two can therefore oversimplify the concepts, for unquestionably leaders both manage and lead, and managers likewise.

Interestingly, Brookes and Grint (2010) describe New Public Management (NPM) as ‘dead in the water’, for it is about dealing with complicated but essentially ‘tame problems’, compared to leadership, which they stress is about ‘coping with wicked problems involving complexity and change’, which, currently arguably, is a feature of everyday public sector services.

They suggest that management is more mechanical, and that New Public Leadership (NPL) works better in a ‘networked governance environment where the overall aim is the delivery of public value’. With this specific focus, managing a steady state is no longer compatible with the significant changes required within Health and Social Care. Indeed, change has been an ongoing feature of all public sector organisations for some time, and therefore leadership rather than management has dominated discussions; because of this emphasis, leadership will be the main feature throughout this text.

A Historical Overview of Leadership Theories

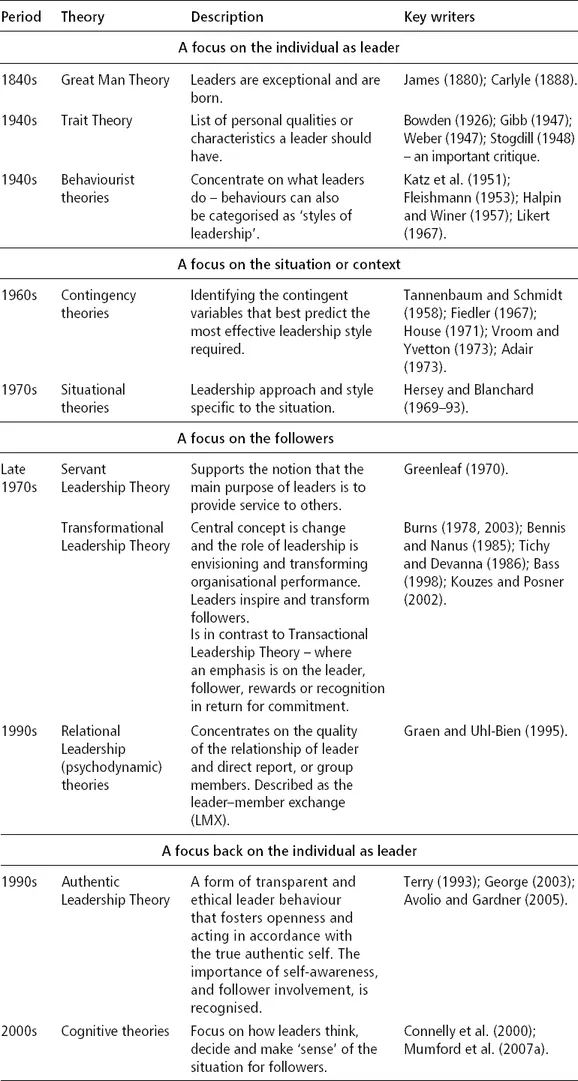

This section examines historical leadership theories, with Table 1.1 capturing some of the most well known. Historically there was a concentration on the individual as the leader who was perceived as genetically born to lead, and the importance of leader traits and behaviours continued this fascination with the individual leader. The situation or context became an important emphasis, followed by the notion of transforming others into leaders, and finally all this has come full circle, returning to individual leaders, but more specifically to the way they think.

A Focus on the Individual as Leader

Great Man Theory

The Great Man Theory of the 1840s proposed that leaders are born with a set of innate qualities and characteristics, or ‘traits’, which only ‘great’ people inherited (Northouse, 2013). The emphasis therefore was on the belief that leaders were born and not shaped or made, were implicitly destined to lead and were primarily male, hence the ‘Great Man’ (Glynn and DeJordy, 2010). Some lists of traits would also include a person's height (Yukl, 1998). They were often distinctly Western and from the military (Bolden et al., 2003, p6).

There was a perceived connection with being brave and heroic, mythical interactions made popular by the writings of Thomas Carlyle (1888) in his book, On Heroes, Hero Worship and the Heroic in History. This fantasy with the ‘hero’ and associated conviction of courage and bravery is a feature that played into the sense of being saved by a ‘super’ human being; inferences are clearly discernible today with the fascination for studying great leaders, and reading their autobiographies with a fixation on a ‘heroic concept of leadership’ (Vroom and Jago, 2007, p18). This emphasis focused attention on the individual's so-called unique personal qualities, with an inference that the many were led by a few gifted and talented individuals.

Advantages

The romantic idea of the leader as a ‘hero’ arguably satisfied the so-called follower's concept, need and ideology of a ‘great leader’ at that time. This perpetuated the belief that individuals, or a situation, could be protected or rescued by the right person – that a great leader would take control and save the day.

Criticisms – Disadvantages

There was a real focus on the leader, and his innate character, as the shaper of history, and not the followers, or the situation that prevailed. This great leader was not only perceived to be male but also of a certain social class. In contrast, contributions of the ‘Great Women’ leaders in history, for example Joan of Arc, Catherine II (the Great), Empress of Russia, and Florence Nightingale, were largely ignored. The concept of one brave super hero to some extent has remained elusive and attractive; although in the National Health Service (NHS), The King's Fund (2011) has recognised this as conceptually flawed.

Depending on a ‘Great’ leader links to Wilfred Bion's work, described by Stokes (1994, p19) as ‘the unconscious at work in groups and teams’. Group members, Stokes suggests, can ‘become pathologically dependent, easily swayed one way or another, by their idealisation of the leader’, and with it there is a loss of challenge, or criticism of the leader, an important feature of a ‘healthy group life’ (1994, p19). Today, Johnson (2005, p3) reminds us that there is more discussion about ‘fallen heroes’ and that the image of the leader as a hero, ‘has been shattered by one ethical scandal after another’.

Importantly, there was no scientific validity to support this theory. In contrast self-leadership focuses on all individuals counting, not a privileged few. The Great Man Theory is clearly linked to the next category, Trait Theory.

Trait Theory

Early Trait Theories

Trait Theory continued the focus on the individual leader and, while popular in the 1930s, Stogdill's (1948) critique of the ever growing list of traits ensured it lost some of its credibility and therefore its appeal, to see a resurgence in terms of interest from the 1990s onwards.

This theory proposes that leaders have distinct traits (either inherited or acquired), which are part of their personality and which enable them to influence others to achieve (Northouse, 2013). An emergent or effective leader, it was believed, possessed a certain set of particular traits that were relatively stable over time, and were distinct from a person's mood (Roberts and DelVecchio, 2000). According to Beeler (2010), ‘traits’ describe thinking preferences, personality, motivation and how leaders interact with others. Bass and Bass (2008, p103) suggest that, ‘when traits are requirements for doing something they are called competencies’.

Individuals who were more dominant, more intelligent and more confident about their own performance were more likely to be identified as leaders by other members of their task group, and these three traits could be used to identify emergent leaders (Smith and Foti, 1998). Kirkpatrick and Locke (1991, p59) supported the notion that individuals could be born, or learn the six key traits they identified: drive, motivation, integrity, confidence, cognitive ability and task knowledge. Others included social intelligence (Zaccaro et al., 2004). Social intelligence is described by Marlowe (1986) as the ability to recognise one's own and others’ feelings, behaviours and thoughts, and to respond accordingly.

Northouse (2013) advocated similar key traits: intelligence, self-confidence, determination, integrity and sociability. Kouzes and Posner (2002, p25) interviewed 75,000 individuals to establish the top perceived characteristics needed in a leader (the data were extrapolated from six different continents: Africa, North and South America, Asia, Europe and Australia); the following are the top ten traits identified:

- Honest

- Forward looking

- Broad minded

- Dependable

- Competent

- Intelligent

- Supportive

- Inspiring

- Fair minded

- Straightforward

Others, such as Judge et al. (2002), suggested that extraversion was the most significant factor, followed by conscientiousness, openness and low neuroticism.

Advantages

This theory supports the notion that there is a set of individuals, with special gifts, who can achieve great things. It fulfils the need for individuals to see their leaders as ‘gifted people’ (Northouse, 2013).

In addition, it provides lists of reported traits that individuals can be assessed and measured against to determine suitability for the role of leader, and while individual traits present little clue, or indicative significance, in combination they can produce predictive patterns. Invariably, whole industries of psychometric testing have emerged to attempt to identify leadership potential, measured against a set of predetermined traits (thinking preferences, personality and predisposition in terms of motivation). Zaccaro (2007) advocated another look at the leadership traits, suggesting that the move away from this area had been premature.

Criticisms – Disadvantages

The trait approach was challenged in terms of its universal application by Northouse (2013), for this emphasis concentrates on the leader and her or his personality, and not the context, or the individuals being led. Focusing on the individual traits distracted attention from the fundamental importance of the relationship between individuals.

The lists of traits that emerged over time have become almost limitless and, without an agreed definitive grouping of tried and tested traits, this has produced long subjective lists. Matthews et al. (2003, p3), for example, refer to Allport and Odbert's (1936) inventory of almost 18,000 personality-relevant terms. The studies supporting the Trait Theory have been described by Northouse (2013) as, ‘ambiguous and uncertain at times’, not robust and consistent. Bolden et al. (2003, p6) concur that, although some traits were identified across studies, there were ‘no consistent’ and conclusive groupings that could be isolated with any degree of universal accuracy; implicitly isolated traits do not define a leader.

Earlier researchers also found no significant differences between the traits of followers and leaders, and also on leadership effectiveness in relation to identified traits (Fleenor, 2007). Implicitly they did not provide ‘sufficient predictors of leadership effectiveness’ (Hernandez et al., 2011).

Concentrating solely on individuals’ traits also fails to take into consideration the impact of the situation (Friedrich, 2010). A person who possesses certain traits can make a leader in one situation, but not in another. Churchill is a classic example of a leader who may not have been recognised for his greatness and specific abilities, had it not been for the Second World War. Traits are also a poor predictor of behaviour. Others may have traits that help them to emerge as leaders but that are not sustained over time. Identifying a prescriptive and definitive list of traits is therefore not only reductionist, and excludes potential, but is also subjective and therefore somewhat flawed. Indeed, according to Bass and Bass (2008, p49) the ‘pure trait theory eventually fell into disfavour’.

Being a leader is far more than simply being intelligent, self-confident and sociable (Caughron, 2010). Indeed, Stogdill and Bass (1990) concluded, after extensive research, that there was no one set of traits that could be linked to successful leadership in all situations.

This reductionist approach arguably leaves no room for potential growth and development, an important and con...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Publisher Note

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Illustration List

- About the Author

- Foreword and Invitation

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Leadership Theories

- Chapter 2 What is Self-leadership?

- Chapter 3 The Foundations of Self-leadership

- Chapter 4 What Determines State of Mind?

- Chapter 5 Self-leadership: Neuroscience Implications

- Chapter 6 Self-leadership and Resilience: A Key to Appropriate Professional Judgement under Pressure

- Appendix: A New Framework for Easy, Effective and Sustainable Leadership Development

- References

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Self-Leadership and Personal Resilience in Health and Social Care by Jane Holroyd,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.