![]()

1

Drugs and Drug Users in Context

The aims of this chapter are to:

- define what a ‘drug’ is

- outline the major licit and illicit drugs along with their effects

- use comparative data to outline the prevalence of drug use

- use comparative data to establish the profile of people in terms of their drug use and the range of issues that they commonly present to specialist agencies as well as health, social welfare and law and order organisations.

In fact and fiction the history of humanity is replete with what Davenport-Hines (2001; 2004) has called the ‘pursuit of oblivion’. In fiction Robert Graves (1992: 9) talks about the drunken God Dionysus and his followers the Maenads and the Centaurs, who washed down copious amounts of hallucinogenic mushrooms with wine and ivy ale thus inducing ‘hallucinations, senseless rioting (involving running around the countryside tearing animals or children in pieces) prophetic insight, erotic energy and remarkable physical strength’. The use of psychoactive substances is a key feature in religious ceremonies from the Jewish Shabbat to the Christian Eucharist, and where alcohol has been proscribed, for example in Islamic countries, then coffee houses and the smoking of tobacco have assumed significance (Weinberg and Bealer, 2001). Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes is a frequenter of opium dens, and there is evidence to suggest that some of the most significant leaders in history, such as Alexander the Great (see Liappas et al., 2003), Stalin (see Sebag-Montefiori, 2002) and Churchill (Storr, 2008) (who was also never seen in public without a Havana cigar), had alcohol problems.

Although there has been the presence of psychoactive drugs in virtually all human cultures it has been the development of the industrial state over the last 300 years, and its commensurate colonial expansion (Gately 2001), that have given rise to the concern with addiction and drug related problems. Drug epidemics are nothing new, and we can consider two that were separated by 250 years. The gin epidemics of the eighteenth century and the heroin epidemics of the 1980s are strikingly similar, in that the contributing factors included urban poverty and the technology to mass produce the drugs and thus to improve the route of entry into the body. The invention of the distilling process to produce spirits allows higher concentrations of alcohol to be consumed and faster, so making drunkenness easier and more likely. Likewise the development of the hypodermic syringe allows heroin to enter into the bloodstream more rapidly for a quicker and bigger ‘hit’. During the 1980s heroin use was found to be ‘widespread’ amongst predominantly socially excluded young people in cities and nearby towns, with estimated numbers between 100 and 150,000 users (Parker, 2005).Within the context of economic decline, and the lack of funding available to health and social services, heroin use had a major impact upon already disadvantaged communities. But compare these numbers with the gin epidemics. The eighteenth century was an age of prodigious drinking with the year 1750 seeing six million people (including children) drink 11 million gallons of gin (Heather and Robertson, 1997). Within the current context of concerns over the increasing consumption of alcohol within western industrialised societies, the situation is not seen as a drug epidemic in the same ways that increasing heroin use was and is seen to be. This is because of the social acceptability of alcohol and the part that it plays in our cultural and social life.

Should we see alcohol as just another drug?

What is a drug?

Take a few moments to jot down what you think a drug is, what drugs you use, what you see as the pleasurable and not so pleasurable consequences of that use, and any experiences you have of trying to change that use.

Goldstein (2001: 4) argues that:

A drug is any chemical agent that affects biologic function … A psychoactive drug is one that acts in the brain to alter mood, thought processes or behaviour. Nothing about drugs as such, even psychoactive ones, makes people like them or try to secure them. On the contrary when physicians prescribe drugs a major difficulty is getting patients to take them regularly … this ‘compliance problem’ is just as troublesome with many psychoactive drugs (such as those used to treat mental illness) as it is with drugs of other kinds.

We all use drugs of one kind or another usually because we have an expectation of the effects of those drugs, whether it is to get high, to relax, or to find some energy. This psychological expectation plays an important role in combination with the biological effects and crucially the social and environmental context as well. We can say that drugs act on the basis of a combination of physical effects on the brain and body, the psychological expectation that the individual has of the effects of the drug, as well as the influence of the peer group and social norms of the individual.

For a drug to work it has to be ingested (see below for different routes of entry to the body). The human brain then sends signals across nerve tracts via a system of chemical messengers which are called neurotransmitters, and which Goldstein (2001) refers to as the brain’s own drugs. Different psychoactive drugs have their own ways of working with these neurotransmitters and can act on the nerve pathways as a mimic of those natural drugs, or to selectively block the activity of the natural drugs, or to enhance the natural action of a neurotransmitter.

The neurotransmitters are described as a kind of ‘chemical key’ which fits into designated ‘keyholes’ which are essentially receptor sites found on the surface of nerve cells. The psychoactive drug may be able to key into and unlock one or more kinds of receptor site and thus have its effect. The role of the brain and its evolutionary development will be discussed in detail in Chapter 6, but at this stage we need to know that particular neurotransmitters are implicated in a reward system that regulates behaviour such as eating, sex and drugs. (The neurobiology of drug use will be discussed in detail in Chapter 6.)

Drug classification

Usually drugs are classified according to the major mode of impact that they have on the mind (Edwards, 2004) and thus the following classifications are used by academics and practitioners:

- sedatives

- stimulants

- opiates

- hallucinogens

- mixed effects

- volatiles.

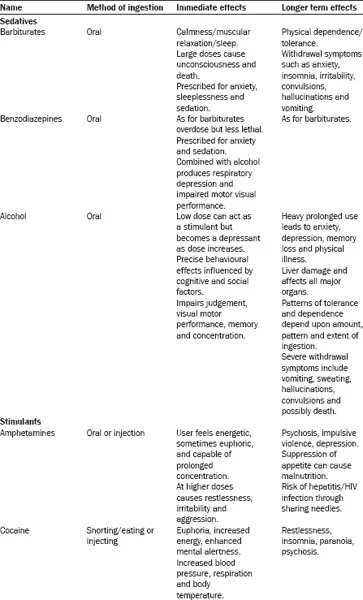

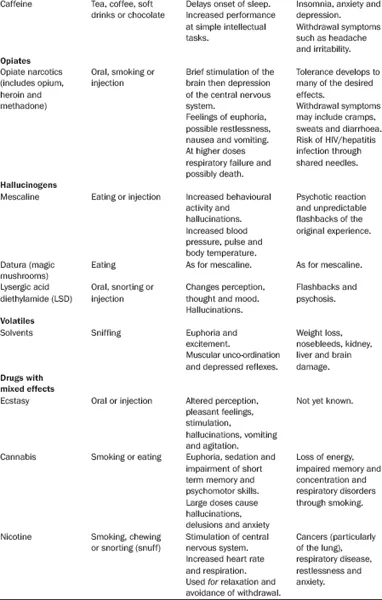

You will see from Table 1.1 that there are both immediate and longer term effects from using drugs (the table is not intended as a definitive guide to all problems experienced) and it is usually the desired immediate effect that is the reason for taking the drug. For example, someone attending a rave might use amphetamines or ecstasy to keep dancing all night, whereas a person wanting to relax may use alcohol or cannabis. However, none of these categories are clearly delineated in the sense that the effects of a particular drug will be mediated by the biology of the individual, the environment in which the drug is used (including other people in attendance), and the expectations that the individual has of the effects of that drug. In addition, of course, people may use a combination of drugs (poly drug use), at the same time, for differing effects. At this stage we are only considering the biological and psychological effects of some drugs. Issues of social control (in the form of legal sanctions based upon notions of relative harms) have not been raised, but will be discussed further in Chapter 2, and neither have the social consequences of drug use, which we will come to later in this chapter.

The worldwide prevalence of drugs

The United Nations Office of Drugs and Crime Prevention produced a World Drug Report (UNODC, 2006). The UNODC estimates that 200 million people worldwide (out of a population of 6,389 million) (4.9% of the population between the ages of 15 and 64) use illicit drugs. Of these 3.9% use cannabis, 0.5% amphetamines, 0.4% opiates, 0.2% ecstasy, 0.4% opiates (of which heroin is 0.3%) and cocaine 0.30%. Within this total population it is estimated that 25 million people (ages 15-64) are involved in problem drug use.

Adult drug use in the UK

In the UK the European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (EMCDDA) (2006), utilising the figures from the British Crime Survey (BCS) to monitor drug use, estimates that approximately one third of the adult population between the ages of 16 and 64 acknowledge having used some kind of illicit drug during their lifetime. People under the age of 35 are far more likely to use illicit drugs, with prevalence of use highest for those under 25 years of age. There is evidence to suggest that the prevalence of use and particularly first time use is declining. Males are more likely to report drug use than females, with those differences tending to become more significant with age. The EMCDDA argues that in 2005/6 based upon the results of 29,631 respondents cannabis was the most widely used illicit drug across all age groups at 8.7%, which was very close to the figure of 10.5% for any drug used. All other drug use was much lower with cocaine at 2.4%, ecstasy at 1.6%, amphetamines at 1.3%, magic mushrooms at 1%, LSD at 0.3% and crack at 0.2%. Opiate use is not included in these figures but the EMCCDA estimates the prevalence of opioid use at a national level to range roughly between one and six cases per 1,000 population aged 15–64.

TABLE 1.1 Drugs and their effects

Source: adapted from Edwards, 2004; Barber, 1995

Poly drug use

Evidence from major studies across the developed world indicates that poly drug use is the norm for many people, and not necessarily those who have a dependency problem. For example, there is an acceptance that a key feature of the club and dance scene is young people experimenting with a variety of substances (Parker et al., 1998). However, within the literature there is disagreement over what the term ‘poly drug use’ should actually entail in terms of substances (whether legal or illegal) and the timings of their ingestion (Hunt, 2007). Studies such as the National Treatment Outcome Study and the Drug and Alcohol Outcome Treatment Study (see below) show that within the ‘clinical’ population this is a major issue in relation to detoxification and rehabilitation.

The European School Survey Project on Alcohol and Other Drugs (ESPAD) (see www.espad.org) was set up in 1994 to study adolescent substance use in Europe from a comparative and longitudinal perspective. Four data collections have taken place from the participating countries in 1995, 1999, 2003 and 2007, with new countries joining for each survey point.

The ESPAD findings clearly demonstrate a strong emphasis on poly drug use amongst those people turning 16 years of age in the year that the data are collected. In the UK the drinking of alcohol by adolescents and drunkenness are above the average for the ESPAD countries as a whole, and have stayed relatively stable since 1995. In 1995 90% of adolescents had consumed alcohol in the last 12 months, and 91% in 1999 and 2003 respectively. This compares to the ESPAD average of 80% for 1995, 82% for 1999, and 81% for 2003. Of even more concern are the figures for drunkenness over the same period, with the UK figures being 70%, 69% and 68% for the respective years as compared to the ESPAD averages of 47%, 51% and 50%. Although alcohol consumption has remained much the same over the same period the use of alcohol and pills in combination has declined from 20% to the ESPAD average of 7%.

By 2003 cigarette smoking amongst adolescents in the UK had fallen below the ESPAD average of 63% to 58%, and also tranquiliser and sedative use standing at 2% as compared to the ESPAD average of 7%. In addition, the use of inhalants which was at 20% in 1995 (compared to the ESPAD average of 9%) had dropped to 12 % in 1995, slightly below the ESPAD average of 10%. However, any drug but cannabis stood at 9% compared to the ESPAD average of 6% and cannabis use was at 38% as compared to the 20% ESPAD average.

The early and increased use of combinations of substances are important factors in the increased risk, not only of drug dependency (Li et al., 2007b) but also of the concurrence of mental health problems (see Chapter 5), as well as the associated problems of poverty and social exclusion.

The UNODC (2006) argues that the demand for drug treatment tends to mirror the availability of particular drugs, with the exception of cannabis. Given the extent of cannabis use across the world only a small proportion of users will seek treatment, although this number is growing in line with use. In Africa most treatment sought is for cannabis, in Asia and Europe it is for opiates, and in South America for cocaine. For the use of amphetamines treatment demand is highest in Asia followed by Oceania, North America, Europe, and Africa.

The social context of substance misuse in the UK

The UK Government (Home Office, 2002) estimated that there are 250,000 Class A drug users (see Chapter 2 for the system of classification) who account for 99% of the costs of drug misuse in England and Wales. The National Drug Strategy (Home Office 1998; 2002) was largely based on the National Treatment Outcome Research Study (NTORS) (see Gossop et al., 2003). NTORS was the first large scale, prospective and multi-site treatment outcome study of substance misusers carried out in the UK. It provides a useful source of information about the problems that service users arrive at treatment with, the ...