![]()

1

Models of Integration

After a brief historical perspective, we first compare a number of different approaches to integration before discussing the ‘approach, method and technique’ framework. Next we define our own stance on integration and discuss current methods of training.

BRIEF HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON INTEGRATION

When we have a problem or are feeling unhappy, some of us like to talk with a person who is not a friend or part of our family. In the past that was often someone respected in the community: a wise woman, a doctor or a spiritual leader such as a priest or shaman. These days that individual is often a counsellor or psychotherapist. It was not until the beginning of the last century, however, that therapy became a profession and developed its own body of knowledge and methodology.

Theories generally do not appear in a vacuum, but in relation to other developments. Freud, regarded as the founder of the ‘talking cure’, was influenced by the philosophy, literature and medical science of his time. This is not to deny Freud’s brilliance; he was a truly original thinker. However, ideas about the unconscious, for example, were also being discussed by thinkers such as the Danish philosopher Harald Hoffding (Hoffding and Lowndes, [1881] 2004) and Carl Jung, whose conception of the unconscious differed significantly from Freud’s view.

Freud’s views were taken up, criticised, modified and developed further by others, a process that still continues; indeed, this is what happens with theories in all disciplines. Having just developed a groundbreaking theory of inner dynamics that may go on inside human beings, however, it was not easy for Freud to acknowledge that others might have ideas that contradicted some of his own. His falling out with, for example, Jung and Reich mark the beginning of the many ‘turf wars’ that have plagued the field from the beginning, such as ‘Freudians’ vs ‘Jungians’, followers of Melanie Klein vs those of Anna Freud or classical analysis vs attachment theory. Currently, we have disputes between those for and against cognitive behavioural therapy, and between the relational psychoanalytic movement and those favouring a classical psychoanalytic approach. While some of these divisions may be characterised as acrimonious, others have maintained a healthy dialogue of difference and innovation on a theme.

As early as the 1930s, French (1933) attempted to integrate aspects of psychoanalysis and Pavlovian conditioning. Reactions were mixed, with some rejecting the idea outright, while others thought it a potentially fruitful line of inquiry. A few years later Rosenzweig (1936) wrote an article with the now famous title, ‘At last the Dodo said, “Everybody has won and all must have prizes”’. This quote from Lewis Carroll’s Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland ([1865] 1962, chapter 3) is referenced in current debates on psychotherapy’s effectiveness, where the term ‘Dodo Effect’ is used as shorthand for a lack of evidence for any difference between approaches. Rosenzweig claimed that effectiveness was attributable to elements all therapies have in common, rather than with differences. He identified three factors:

- Effectiveness is related to therapists’ personalities, rather than their theoretical approach.

- All therapies tend to help people see their problems differently.

- Although therapies differ in focus, all are likely to be helpful as change in one area will also affect other areas (Rosenzweig, 1936). (This claim seems to anticipate some principles within a systems approach, which we will discuss further in the next chapter.)

Many subsequent writers have been more interested in the similarities between therapeutic approaches than their differences. Until relatively recently, however, they were in the minority, perhaps because psychotherapy was still young and the zeitgeist was not yet ready to accept an integrative view. This began to change in the 1960s with Frank and Frank ([1961] 1993) discussing commonalities between psychotherapy and other forms of healing and Carl Rogers (1963) claiming that the traditional borders between the various therapeutic approaches were beginning to disintegrate. Interestingly the third edition of Frank and Frank’s book Persuasion and Healing was reprinted in 1993, which seems to indicate that integrative ideas emerging in the 1950s and 1960s formed the roots of a general movement towards integration as a mainstream approach in therapy.

From the late 1980s onwards there has been increasing emphasis on the importance of the therapeutic relationship, irrespective of theoretical approach. Lazarus (1981) took a pragmatic view and saw no problem with therapists borrowing techniques from other modalities, without necessarily taking on board the theory upon which these techniques were based. Lazarus coined the term ‘technical eclecticism’ for this practice and later developed his ideas further into ‘multimodal therapy’ (Lazarus, 1981). The 1980s saw an explosion of publications and conference presentations and integration came to be regarded as a significant movement.1

In recent years we have observed two distinct phenomena. On the one hand, as mentioned earlier, there are ongoing disagreements between the proponents of a number of different theoretical approaches. On the other hand there appears to be a general growing together in the theory and practice of approaches hitherto regarded as distinct. We will discuss these phenomena in more detail in chapter 2.

CURRENT APPROACHES TO INTEGRATION

Since the early founders of the ‘talking cure’, the body of therapeutic knowledge has increased dramatically, giving rise to many different models within three broad categories of approach: psychodynamic, humanistic and cognitive-based. Integrative approaches, which constitute a combination of two or more models within the above approaches, might be seen as a fourth category. We say ‘might’ as there is always the danger of setting any approach in concrete. Even within the three main categories, there are many new models that are influenced by several others. The fact that there are so many variations in theoretical approach indicates that the field is very ‘alive’ and developing in response to the complexity of human circumstances and the evolving nature of knowledge.

Re-invention of Wheels?

Our Western society appears to lend itself to pluralism and competition (O’Brien and Houston, 2007). Practitioners within one approach may be ignorant of other theories, resulting in duplication and ‘re-invention of wheels’. For example, there is a current movement within the psychoanalytic world towards a more relational (Mitchell and Aron, 1999; Mitchell, 2000) and intersubjective approach (Stolorow et al., 2002; Stern, 2009). At the same time this does appear to be a (re)discovering of many beliefs and practices that have always been a part of therapies based on a humanistic philosophy. It is not always clear whether these are true ‘discoveries’ or whether people are using work from other fields without acknowledging that they are doing so. For example, despite a great deal of overlap with the humanistic-existential field, Carl Rogers is never mentioned in psychoanalytic literature (O’Brien and Houston, 2007: 4).

Jungian psychology appears rather on the sidelines in the official psychoanalytic literature and is rarely included in training. At the same time, Jungian concepts such as ‘complexes’, or intro- and extraversion have filtered through into everyday language. The literary and artistic fields have been widely influenced by Jungian psychology. For example Women Who Run with the Wolves, by the Jungian analyst Clarissa Pinkola Estes (1997) became a bestseller, and the science fiction series Dune by Frank Herbert had the ‘collective unconscious’ as its main concept. Other artists influenced by Jungian ideas include Italian filmmaker Frederico Fellini, the painter Jackson Pollock and the singer-songwriter Peter Gabriel. The Myers-Briggs personality test (Briggs Myers, 1962), which is widely used within the business world, is based on Jungian typology and Jung’s ideas also indirectly influenced the twelve-step programme of addiction recovery.2

Often, however, borrowing and sharing of ideas is acknowledged. Schema-based cognitive therapy, for example, acknowledges its use of Gestalt theory (Young et al, 2006). Overall it seems that the zeitgeist3 is moving towards a more integrative stance, which (as we will discuss in chapter 2) is in line with postmodern philosophy. It may be that commentaries and critiques of therapeutic approaches recognise that the field is as subject to conceptual cross-fertilisation, analysis and synthesis as other fields of intellectual and scientific endeavour. The conditional nature of knowledge is well recognised in the so-called hard sciences (Kuhn, 1962; Popper, 2002). Therapy, which spans sciences, humanities and the arts is subject to similar social and theoretical evolution and integration. The challenge is to conceptualise such integration as a synthesis rather than a cacophony of jarring concepts thrown together randomly. At the same time – who is to judge?

This may also be a result of the field of counselling and psychotherapy beginning to mature (O’Brien and Houston, 2007).

KEY CONCEPTS OF INTEGRATION

The key concepts of psychotherapeutic integration are set out in the box below.

A Metaphor

This is an experience one of us had recently:

The above experience may be seen as a metaphor for different types of theory. Some may focus on one aspect of human experience, some on another, but none are likely to be able to encompass the entire richness of life. If we rely on just one theory, or only one set of instructions as in the above example, we might miss something important or lose our way. We believe that every theory offers useful reference points, which may be a reason why many practitioners are attracted to integration.

Typically integrative therapy involves combining different theoretical approaches and accompanying methods. As there are many models within the main theoretical approaches, it follows that there are also many different ‘integrations’, depending on which models or part models are being integrated. McLeod (2003b) fears that the proliferation of integrative models may add to the fragmentation of the field of counselling and psychotherapy. We do not share this fear and agree with O’Brien and Houston (2007: 4) who take the opposite view and regard integration as ‘a corrective tendency in an over-fragmented field’.

The Eclectic – Integration Continuum

According to McLeod (2003b: 64) the world of counselling and psychotherapy is involved in an ‘important debate over the relative merits of theoretical purity as against integrationism or eclecticism’. However, eclecticism, within which a practitioner may employ a wide range of techniques without a unifying theory, seems less popular than integrationism, which does attempt to unify different theories.

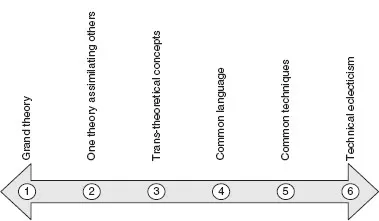

Mahrer (1989) identified six methods of integration comprising: the development of a new grand theory capable of encompassing all existing theories; using one theory to assimilate others; developing a common language, trans-theoretical concepts or techniques; and technical eclecticism – evidence-based approaches that marry specific problems with particular techniques (Dryden, 1984). The six approaches may be mapped onto a continuum with integration through a unifying theory at one end and the eclectic approach, focusing only on techniques, at the other.

Figure 1 The Eclectic – Integration Continuum

According to Cooper and McLeod (2007) the ‘grand theory’ as well as some trans-theoretical attempts at integration may end up as unitary or purist rather than integrative models. We agree with Mahrer (1989) and Lapworth et al. (2001) that the trans-theoretical and technical eclecticist approaches seem the most viable options. What these approaches have in common is that, despite being placed in different positions on the continuum, each constitutes a partial rather than a complete integration. We see this as an advantage rather than a limitation (McLeod, 2003b: 69), as complete integration seems neither possible nor desirable. This is because eac...