- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Reworking Qualitative Data

About this book

What is qualitative secondary analysis? How can it be most effectively applied in social research?

This timely and accomplished book offers readers a well informed, reliable guide to all aspects of qualitative secondary analysis.

The book:

· Defines secondary analysis

· Distinguishes between quantitative and qualitative secondary analysis

· Maps the main types of qualitative secondary analysis

· Covers the key ethical and legal issues

· Offers a practical guide to effective research

· Sets the agenda for future developments in the subject

Written by an experienced researcher and teacher with a background in sociology, the book is a comprehensive and invaluable introduction to this growing field of social research.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

What is Secondary Analysis?

The analysis of pre-existing data in social research

Functions of secondary analysis

Modes of secondary analysis

Conclusion

Notes

Secondary analysis is best known as a methodology for doing research using pre-existing statistical data. Social scientists in North America and Europe have been making use of this type of data throughout the twentieth century, although it was not until 1972 that the first major text on the research strategy, Secondary Analysis of Sample Surveys: Principles, Procedures and Potentialities by Herbert H. Hyman, was published. Since then, the literature on secondary analysis of quantitative data has grown considerably as the availability and use of these data has expanded. There is now a substantial body of work exploring different aspects of the methodology, including several textbooks describing the availability of statistical data sets and how they can be used for secondary research purposes (see Dale et al., 1988; Hakim, 1982; Kiecolt and Nathan, 1985; Stewart and Kamins, 1993), as well as critical commentaries on the scientific, ethical and legal aspects of sharing this type of data in the social sciences (see Fienberg et al., 1985; Hedrick, 1988; Sieber, 1988, 1991; Stanley and Stanley, 1988).1 Accordingly, the terms ‘secondary analysis’, ‘secondary data’ and ‘data sharing’ have become synonymous with the re-use of statistical data sets.

However, in recent years interest has grown in the possibility of re-using data from qualitative studies. Since the mid-1990s a number of publications have appeared on the topic written by researchers who have carried out ground-breaking secondary analyses of qualitative data (Heaton, 1998; Hinds et al., 1997; Mauthner et al., 1998; Szabo and Strang, 1997; Thompson, 2000a; Thorne, 1994, 1998), by archivists involved in the preservation of qualitative data sets for possible secondary analysis (see Corti et al., 1995; Corti and Thompson, 1998; Fink, 2000; James and Sørensen, 2000) and by academics interested in these developments (see Alderson, 1998; Hammersley, 1997a; Hood-Williams and Harrison, 1998). The extension of secondary analysis to qualitative data raises a number of questions about the nature of this research strategy. What is secondary analysis? How does the secondary analysis of qualitative data compare to that of quantitative data? And how is secondary analysis distinct from other quantitative and qualitative methodologies used in social research?

In this chapter, I explore these issues by comparing and contrasting the ways in which secondary analysis has been conceptualized as a methodology for re-using quantitative and qualitative data. I begin by examining the types of pre-existing data which are deemed to be subject to secondary analysis and related methodologies. This is followed by an outline of the purported functions of secondary analysis and how these are more – or less – accepted in relation to the re-use of quantitative and qualitative data. In the last section, I describe three modes of secondary analysis and the emphasis given to each in existing conceptualizations of quantitative and qualitative secondary analysis respectively. The chapter concludes with a provisional definition of secondary analysis which clarifies the focus of this book, as well as providing a basis for the subsequent exploration of the theoretical and substantive issues arising from this conceptual overhaul.

The analysis of pre-existing data in social research

Although the secondary analysis of quantitative data is an established methodology in social research, there is no single, unequivocal definition of the approach. Existing conceptualizations of quantitative and qualitative secondary analysis tend to refer to various propositions, some of which are more accepted than others. The first and most rudimentary principle of secondary analysis is that it involves the use of pre-existing data. This view is exemplified by the following who, writing on the secondary analysis of statistical data, claim that: ‘Secondary analysis must, by definition, be an empirical exercise carried out on data that has already been gathered or compiled in some way’ (Dale et al., 1988: 3). There are, however, notable differences in the types of pre-existing data which are subject to secondary analysis, depending on the nature and origin of the material.

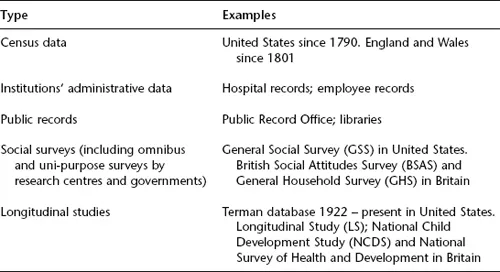

Table 1.1 Examples of pre-existing quantitative data used in social research

Quantitative data

Pre-existing data used in quantitative secondary analysis has been derived from various activities, including research projects carried out by academics, government agencies and commercial groups, as well as the administrative work of public authorities and other organizations that routinely keep records for management purposes.2 Table 1.1 shows examples of the kinds of statistical data that have been used in secondary research in the social sciences, derived from previous research studies and from other contexts.3

For early social researchers, the main types of pre-existing quantitative data available to them were census and administrative records. Durkheim (1952), for example, used both types of data in his classic study on suicide and Miller (1967) used administrative data in her study of former ‘mental patients’ adjustment to the world after discharge from hospital. As Hyman (1972) observes these resources were more difficult to use in the past. Nowadays census data can be stored, shared and analysed with the help of computers; services have also been developed to help distribute the data and to advise researchers on how to use it. Unsurprisingly, the use of census data has expanded, while administrative data is still used on a more occasional basis. It has been suggested that more use could be made of the latter data in areas such as nursing research (see Herron, 1989; Jacobson et al., 1993; Lobo, 1986; Reed, 1992; Woods, 1988).4

Since the 1960s, various types of social surveys have been conducted by government agencies, academics and commercial organizations and the resulting data made available for secondary research purposes. Hakim (1982) distinguishes multi-purpose (or omnibus) social surveys from those designed with an exclusive primary focus. As the name suggests, multi-purpose surveys are carried out in order to provide data for multiple uses (and users). In the United Kingdom, examples of multi-purpose surveys include the General Household Survey (GHS) and Labour Force Survey (LFS), which are carried out by the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The British Social Attitudes Survey (BSA) conducted by the National Centre for Social Research (NatCen) is another example of a survey carried out to provide data for others to analyze. Its American equivalent, the General Social Survey (GSS), has been carried out annually since 1971 by the National Opinion Research Center (NORC) based at the University of Chicago. Cross-national projects have also been developed, such as the International Social Survey Programme (ISSP) (Procter, 1995).

In contrast, more exclusive social surveys are designed to investigate particular research questions and are conducted on a one-off or less regular basis. Given that such surveys are designed to examine specific issues, the scope for secondary analysis may be more restricted compared to data derived from omnibus social surveys (Dale et al., 1988: 9). The same caveat applies to other statistical data collected for specific rather than generic research purposes. However, these data sets are still used as a resource for secondary research purposes. For example, data from the Nuffield study of social mobility in England and Wales (Goldthorpe, 1980) have been re-used on various occasions.

Some statistical data sets have been generated with a view to both primary and secondary research uses. For instance, longitudinal studies follow up a population cohort over time, collecting data on topics of long-term interest and further topics for investigation may be introduced as the study progresses. These data are subject to primary analysis by the researchers who collected the data to address particular research questions; they may also be archived and used by other researchers to address additional research questions. Longitudinal studies have been most extensively carried out in the United States. The oldest ongoing American longitudinal project is the Lewis Terman study which began in 1921/2. It was originally designed to investigate the maintenance of early intellectual superiority over a ten-year period, and subsequently expanded to examine the life paths into adulthood of gifted individuals and the experiences of these individuals and their families. Data from the Terman database have been used in secondary studies, for example, Elder et al. (1993) used its data on World War II veterans in their secondary study of military service in World War II and its effect on adult development and aging.

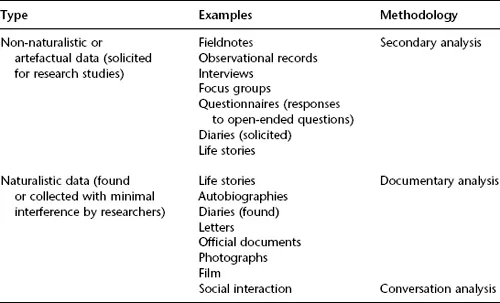

Table 1.2 Examples of pre-existing qualitative data used in social research

Longitudinal studies have also been carried out in other countries, though not to the same extent. Hakim (1982) describes five national longitudinal studies carried out in England and Wales or Great Britain, of which only three followed up the sample beyond two years: the OPCS Longitudinal Study (LS), the National Child Development Study (NCDS) and the National Survey of Health and Development (NSHD). Other non-national longitudinal projects carried out in England include the Newsons’ study of child development (Newson and Newson, 1963, 1968, 1975). New ‘linked’ data sets may also be generated by combining selected data from these resources (Dale et al., 1988). For example, the aforementioned OPCS Longitudinal Study, now known as the ONS Longitudinal Study (LS), links data obtained from the 1971 Census onwards with data obtained annually from public records for those born on one of four days of the year.

Qualitative data

In contrast to quantitative research where, as we have seen, secondary analysis encompasses the use of pre-existing data derived from research and other contexts, in qualitative research different methodologies have been used for the analysis of ‘non-naturalistic’ data that were solicited by researchers, and ‘naturalistic’ data that were ‘found’ or collected with minimal structuring by researchers (see Table 1.2).5,6

In qualitative research secondary analysis is more narrowly conceptualized as a methodology for the study of non-naturalistic or artefactual data derived from previous studies, such as fieldnotes, observational records, and tapes and transcripts of interviews and focus groups. However, unlike quantitative research, there is no tradition of re-using data from previous qualitative studies. On the occasions where research data have been re-used it has tended to be in exceptional circumstances, such as when anthropologists have analysed the fieldnotes of researchers who have died before completing their work and published the results posthumously (Sanjek, 1990a). It is only relatively recently that researchers have begun to recognize the potential for re-using the various types of qualitative data produced in the course of social research, and to publish secondary studies using these resources (Heaton, 1998).

By contrast, naturalistic data such as diaries, essays and notes, autobiographies, dreams and self-observation, photographs and film have traditionally been studied using the more established methodology of documentary analysis (Jupp and Norris, 1993; Plummer, 1983, 2001; Scott, 1990). Documentary analysis has also been used to study some types of textual and non-textual data from qualitative studies which are near-naturalistic in that they were obtained with minimal shaping by researchers (as in unstructured interviews), or by using unobtrusive or even covert methods. However, some types of qualitative data can be construed as naturalistic or non-naturalistic, depending on how they originated. For example, diaries can be kept as a personal record and later ‘found’ and examined by researchers; alternatively, they can be designed and completed as a research tool. Similarly, life stories may be told and recorded in autobiographies, biographies or interviews, and may be more or less structured by journalists, biographers or researchers. Thus, although secondary analysis and documentary analysis tend to focus on non-naturalistic and naturalistic data respectively, this distinction is not always clear-cut and hence there is some overlap in the types of data which are subject to these methodologies.

Life stories solicited for qualitative studies are unique data in that although they tend to be collected primarily for single use, as part of a research study investigating a specific question, they are also recorded with the intention of archiving them for possible future use in other research. For this reason they are similar to the kind of statistical data obtained in longitudinal studies in terms of being collected with both primary and secondary uses (and users) in mind. However, although life stories have been recognized as potentially valuable secondary resources (Atkinson, 1998; Thompson, 1998) and probably archived more than any other varieties of qualitative data, it is not clear to what extent, and how, researchers have used these pre-existing data. There is little published national or international information on the extent and nature of use of these resources generally.7 In addition, there have been no recent reviews of the use of life stories in social research and whether these were obtained from archives or through primary research.8 There is also little guidance on how to do social research using pre-existing life stories: textbooks tend to focus on how to collect, record and analyze life stories in the context of primary research rather than how to access and undertake secondary research using pre-existing life stories deposited in archives (see Atkinson, 1998; Langness, 1965; Miller, 2000; Yow, 1994).

The nearest qualitative equivalent to omnibus social surveys designed to provide statistical data for use in multiple studies are projects which have been undertaken to collect and preserve textual and non-textual remnants of social life. The Mass Observation project is a prime example of this type of work. Described as an ‘anthropology of ourselves’ (quoted in Calder and Sheridan, 1984: 247), various materials were gathered by the investigators on the project between the 1930s and 1950s and more recently during the 1980s and 1990s. Various non-naturalistic and naturalistic data were collected, including reports of interviews and observations, time sheets and diaries, and original documents, such as press cuttings, pamphlets, and photographs. These data were collected and archived with a view to their value as a historical resource and more general utility. The archivist (Sheridan, 2000) notes that these data have been used by academic researchers from a range of disciplines (including art history, social history, anthropology, psychology, sociology, media and cultural studies) as well as by the wider community (including the media, novelists, artists, teachers and students). She adds that since 1970 social research using the data has taken four main forms: as evidence in historical research; in the study of the Mass Observation movement itself; in methodological research; and to inform the development of related initiatives. In principle, the re-use of some of the data from the Mass Observation project may therefore be defined as documentary or secondary analysis, depending on which type of data is used and for what purposes (of which more below).

Another methodology which has been used in social research to study naturalistic data in the form of recordings of everyday social interaction is c...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of tables

- Preface

- Acknowledgements

- 1 What is Secondary Analysis?

- 2 From Quantitative to Qualitative Secondary Analysis

- 3 Types of Qualitative Secondary Analysis

- 4 Epistemological Issues

- 5 Ethical and Legal Issues

- 6 Modi Operandi

- 7 The Future of Qualitative Secondary Analysis

- Appendix A The Literature Review

- Appendix B Criteria for the Evaluation of Qualitative Research Papers

- Bibliography

- Key Names and Titles Index

- Subject Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Reworking Qualitative Data by Janet Heaton in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Science Research & Methodology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.