- 176 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Achieving Positive Outcomes for Children in Care

About this book

For over a decade and with the best of intentions, the U.K. government has spent millions attempting, but largely failing, to improve personal, social and educational outcomes for children and young people in public care. In this book, the authors explain why the problems of this highly vulnerable group have resisted such effort, energy and expenditure and go on to show how achieving positive outcomes for children in care is possible when the root causes of failure are tackled.

Topic covered include:

- The power of parenting

- The impact of parental rejection on emotional development

- Support for the adaptive emotional development of children and young people

- Practical advice on introducing the ?Authentic Warmth? approach into existing childcare organisations

- Future issues in childcare

This book is essential reading for carers, commissioners, policymakers, support professionals, educational psychologists, designated teachers and students of social work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Achieving Positive Outcomes for Children in Care by R J Cameron,Colin Maginn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Professional Childcare: When?

The supreme happiness of life is the conviction that we are loved.

(Victor Hugo, French novelist, 1802–85)

What makes a child carer a professional? Is it that they possess specialist knowledge and skills? Or is it just the fact that they are paid to look after other people’s children? Our motivation for writing this book stems from our vision that, some day, the answer to this question will be an emphatic statement that includes the words ‘a highly specialised knowledge of children’s developmental needs, combined with effective therapeutic skills’. To reach this point in professional development, we would have to ensure that the knowledge and skills of carers can be effective, evidence based, flexible, dynamic (as opposed to static), drawing heavily on the knowledge-base of psychology, and not intimidated by our risk-averse legal system or frozen by political correctness.

There is still a long way to go to ‘professionalise’ childcare, not the least because almost everyone believes that they are experts in childcare. We have all been children and we have all retained the detailed and intimate knowledge of our own childhood. We know what we liked and disliked about the way we were brought up and, as individuals, we are well aware of what we think worked for us and we can vividly recall what did not. In retrospect, we can see how we spent our childhood years in building our view of the world and absorbing the norms of our culture. So, almost all of our own parenting styles, strategies and beliefs stem from our personal experiences of how we were brought up. Because these experiences were so powerful, most of us feel that we are general experts in parenting, rather than individuals who have been recipients of a specific parenting process.

As if universal ‘expertosis’ was not a big enough obstacle to a professional approach to childcare, few other professions have to surmount the claim that the skills which underpin it are ‘instinctive’. Since we are part of the animal kingdom, where parenting is considered a natural and almost universal phenomenon, then what we do not already know (or have experienced during our own childhood) can be supplemented by instinct. If this is the case, surely the raising of other people’s children should be a relatively straightforward task?

So what is the problem with this ‘innate-plus-acquired’ parenting skills’ theory? After all, our close relatives, the gentle gorillas, mostly seem to be doing a competent job raising their offspring: they have no need for parenting books and gorilla children’s homes are unheard off. The adult male silverback frequently takes on the parenting role when weaned gorillas are orphaned. Similarly, the reed warbler’s dedicated care of its eggs is so strong that it can be ruthlessly exploited by the cuckoo which seizes an unguarded moment to deposit her egg in the reed warbler’s nest, so that the emerging cuckoo chick will be brought up by a first-rate stepmother. Indeed, the natural world has other fascinating examples of ‘substitute carers’ which are interesting because they are exceptional: the most likely outcome for abandoned offspring in the natural world is that they end up as the meal of a predator or meet some other untimely end.

Children in Public Care

Over the ages, specific human societies have developed sets of moral codes and legal obligations that have at their core the protection of the vulnerable youngster. Yet in terms of human evolution it is only relatively recently, with the Poor Law of 1563, that poor children in Britain were formally recognised as being in need of state support at all. Indeed, in his book The Invention of Childhood, Cunningham (2006) observed that in the history of childhood we are constantly confronted with parents trying to cope with the deaths of their children, and children facing the possibility of their own deaths. It was not until the advent of eighteenth-century industrial Britain that child mortality rates began to drop. Before this, children died in large numbers from disease, malnutrition, negligence and abuse, or depended on the ‘poor house’ or the philanthropy of the community or the church.

While we in Britain are currently enjoying a society which directs considerable resources towards the needs of our children, these sobering historical facts are an important reminder that we should not underestimate the primary needs of children, that is, basic health care and food. But what else do successful residential or foster carers have to do to ensure that the children and young people they look after become healthy and happy adults who go on to succeed in relationships, provide a loving home for their own children, and lead fulfilling and independent adult lives?

For those children who have been abused, neglected and rejected and who have been removed into public care, the outcome of what is meant to be a benign act by society often turn out to be disappointing, disheartening or despairing. Jackson and McParlin provide a sobering summary:

Children who grow up in local authority care, ‘looked after’ under the Children Act 1989, are four times more likely than others to require the help of mental health services; nine times more likely to have special needs requiring assessment, support or therapy; seven times more likely to misuse alcohol or drugs; 50 times more likely to wind up in prison; 60 times more likely to become homeless; and 66 times more likely to have children needing public care. (Jackson and McParlin, 2006, p. 90)

Table 1.1 Government initiatives to improve the quality of life for children and young people in care

- Quality Protects. In September 1998 the government launched ‘Quality protects’ At that time, the Secretary of State for Health, Frank Dobson, introduced the idea of ‘corporate parents’ when, addressing local authority councillors, he suggested that they should ask themselves ‘Is this good enough for my child?’ ‘Quality protects’ funding was provided to local authorities, based on targets set by the government, which aimed at improving outcomes for looked-after children. Improving educational outcomes was a top priority

- Every Child Matters. Following the death of Victoria Climbié, and the subsequent Inquiry by Lord Laming, in September 2003 the government launched their ‘Every Child Matters’ initiative, which set out five key outcomes or goals for every child. These are: being healthy; staying safe; enjoying and achieving; making a positive contribution; and achieving economic well-being. Looked-after children were targeted for special help and local authorities were viewed as needing help and guidance on how they placed children in need. Out of this paper came the central government paper ‘Choice protects’ which specifically set out to increase the number of foster placements for looked-after children

- Care Matters. In October 2006 the Green Paper Care Matters: Transforming the Lives of Children and Young People in Care opened with an acknowledgement from the Secretary of State for Education and Skills, Alan Johnson, that ‘The life chances of all children have improved but those of children in care have not improved at the same rate. The result is that children in care are now at greater risk of being left behind than was the case a few years ago – the gap has actually grown’. The subsequent White Paper, ‘Care Matters: Time for Change’ in June 2007, shows a determination to improve the quality of life for children in care and reiterates many of the concerns which had already been identified in ‘Quality protects’, including the importance of education

Given the amount of specifically targeted funding for looked-after children by UK central government initiatives such as ‘Quality protects’ (DfES, 2000) ‘Choice protects’ (DfES, 2003), Children’s Workforce Strategy and ‘Every Child Matters: change for children in social care’ (DfES, 2005a; 2005b) it would seem unlikely that all the failings of the care system, highlighted above, are mainly resource related or due to political apathy. (See Table 1.1 for a summary of some of recent and major central government initiatives.)

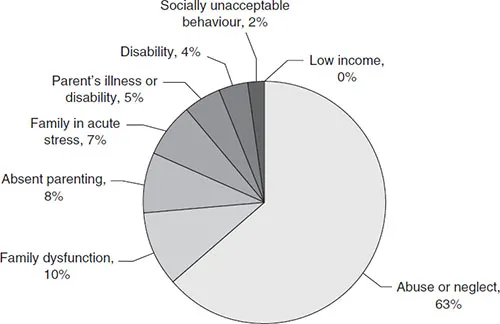

What is particularly poignant about children and young people in public care is that, unlike the common, media-fuelled perception of these children and young people belonging to ‘hoodie’ gangs, subject to anti-social behaviour orders and who ‘terrorising’ communities, the majority of children who are taken into care are there through no fault of their own. The Office for National Statistics (2005) found that the reasons for placement were: abuse and neglect (42 per cent), family dysfunction (13 per cent), intense family stress (12 per cent), parental illness (7 per cent) and socially unacceptable behaviour (6 per cent). The figures produced in the DfES (2006) publication Care Matters: Transforming the Lives of Children and Young People in Care rated the ‘socially unacceptable behaviour ’ group as 2 per cent of the total (see the pie chart in Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Children in care at 31 March 2005 by category of need

Returning to our vision of specialist knowledge and skills in professional childcare, according to the Children’s Workforce Development Council (2008) there are about 170,000 adults responsible for the care of the 60,000-plus children and young people in public care. Given the poor outcomes and the clear pointers from the work of Jackson and McParlin (2006) an obvious conclusion is that this large group of professional carers has been let down by the insights from their own childhood, their culture and their parenting instincts; however, closer examination reveals a more complex explanation.

From Conflicting Views to Shared Purpose

The development of the ‘Authentic Warmth’ model of childcare described in this book, began in 2003 with a heated professional disagreement between the two authors, when Colin Maginn who was the director of two London children’s homes and Seán Cameron, a child and educational psychologist working at University College London, embarked on an applied research project.

Colin had strongly disagreed with one of the conclusions in a published article on enhancing resilience in looked-after children (Dent and Cameron, 2003). Their contention was that as well as the long-recognised risk factors in the lives of these children (such as illness and disease, economic adversity, exposure to violence, living in a drug and crime context, social and emotional deprivation, maltreatment at the hands of adults and other children, poor parenting and so on) a further factor could now be added to this risk list – being in public care. Colin’s view was that a conscientious social worker or placement officer, could be influenced by such a conclusion and use it to avoid exposing children to such ‘further risks’ and decide to leave children who are at risk, with abusive, neglectful and rejecting parents. This is a concern, which has since been expressed in the 2008 the Welsh Assembly’s review of the impact of care on children’s welfare (Forrester et al., 2008).

Dent and Cameron’s uncompromising statement about a failing corporate care system had stemmed from a number of outcome studies, which had shown that large numbers of looked-after children and young people had ended up jobless, homeless and friendless. As evidence of just one of the major deficits in the children’s services, a number of studies had highlighted the inability of children in care to benefit from the power of schools as a potential force for positive change in their lives.

In 1998, Jackson and Martin had written an influential article to illustrate the importance of the education dimension in the lives of looked-after young people. They had located and interviewed a group of high achievers who had grown up in care and confirmed the importance of educational success, as an important resilience-building factor that had helped children bounce back from adversity and to improve their life chances. Yet, as Jackson and Martin pointed out, many residential care staff were unaware of the potential power of education for the positive development of children in care:

No facilities were provided for doing homework, there were seldom any books on the premises, few respondents could remember ever being read to by a member of staff. It was difficult to find a quiet space to read or work … (Jackson and Martin, 1998, p. 577)

Bad practice may account for some of the failings highlighted by Jackson and Martin and the additional risk factor highlighted by Dent and Cameron but both studies had ignored the reality observed by Colin and his staff, that when the children arrived at the children’s home, they were mostly unhappy, confused and angry, suffering from major attention and concentration difficulties, and exhibiting such violent and aggressive behaviour that it was a challenge to get them to settle to any activity, let alone more formal lessons in school.

While the academic view appeared to single out a failing care system as being responsible for the poor life trajectories of many looked-after children, the reality for care staff was that the children being placed in their care were troubled and troublesome before they came through the door.

Taken as a whole, children in care have more difficulties when they enter care than most children. Most have experienced serious social disadvantage, abuse and neglect and other problems. As a result they have a far higher rate of emotional and behavioural difficulty, health problems, poorer educational performance and complex family relationships. (Forrester et al., 2008, p. 4)

In many children’s homes, providing an academic learning environment, reading materials and opportunities for doing homework often may have seemed like secondary priorities when compared with the challenges for care staff of dealing with umpteen temper tantrums, systematic destruction, anger, and violence and extreme unhappiness.

It would seem that poorly trained carers not only had to deal with children traumatised by their previous neglect abuse and rejection but, perversely, these same carers had to deal with ill-informed public representatives and officials who sometimes used the simplistic correlations from published statistics and research to hold carers accountable for the natural but disruptive process of the children working through their traumatic pre-care experiences. Ignoring this was like arguing that the staff in fracture clinics were somehow responsible for the fact that the clinics are full of people with broken limbs!

However, the point where the research and the practice views began to converge was the significant mismatch between the National Vocational Qualification (NVQ) Level 3 training (which is the minimum requirement for all residential care staff) and the day-to-day practice skills which carers needed to work effectively with troubled and troublesome children. Clearly, the NVQ Level 3 curriculum, neither met the theoretical insights needed to work with these children nor the practical skills required to support them.

Concluding Comments

Our work on developing a model for professional childcare practice set o...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- List of Figures and Tables

- About the Authors

- Acknowledgements

- 1 Professional Childcare: When?

- 2 The Power of Parenting

- 3 The Pillars of Parenting

- 4 Managing Challenging and Self-limiting Behaviour

- 5 Supporting Adaptive Emotional Development

- 6 The Education Dimension

- 7 Psychological Consultation and Support

- 8 Theory into Practice

- 9 Into the Future

- Appendix 1 A Sample of Questions Included in the Broaden and Build Checklist for Organisations Wishing to Bring about Fundamental Changes in their Support for Children and Young People Who Are in Public Care

- Appendix 2 A Summary of the ‘Authentic Warmth’ model of Professional Childcare

- Appendix 3 National Care Standards for Young People in Residential Care in Scotland

- References

- Index