eBook - ePub

The SAGE Handbook of Social Work

- 808 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The SAGE Handbook of Social Work

About this book

This Handbook is the world?s first generic major reference work to provide an authoritative guide to the theory, method, and values of social work in one volume.

Drawn from an international field of excellence, the contributors each offer a critical analysis of their individual area of expertise. The result is this invaluable resource collection that not only reflects upon the condition of social work today but also looks to future developments.

Split into seven parts, the Handbook investigates:

- Policy dimensions

- Practice

- Perspectives

- Values and ethics

- The context of social work

- Research

- Future challenges

It is essential reading for all students, practitioners, researchers, and academics engaged in social work.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The SAGE Handbook of Social Work by Mel Gray, James Midgley, Stephen A Webb, Mel Gray,James Midgley,Stephen A Webb,Author in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

SECTION 1

Welfare, Social Policy, and Social Work

INTRODUCTION

Section 1 on welfare, social policy, and social work examines welfare theory and its various approaches, including issues relating to the transformation of welfare and the nature and influence of social policy. The contemporary welfare state debate revolves around changing definitions of and ideas about welfare, the changing institutions responsible for its delivery, the implementation of welfare legislation and policy, and the practices in and through which welfare is delivered, today often referred to as welfare governance. There seems to be some agreement that claims as to the dismantling of the welfare state and the welfare state crisis is overstated. What functions does social work play as a functionary of welfare in regulating the poor? Arguably both relief practices and labour laws have the same general purpose, ‘to augment the regulation of labor by compensating for the vagaries and weaknesses of control based largely on market incentives’ (Piven & Cloward, 2010, p. 167). This section provides a fresh and contemporary examination of the role of social work as part of relief in a transformed welfare state. Relief – or welfare more broadly – gives government a large and important role in the market-oriented capitalist system and becomes a central political issue within an electoral system on which government depends for its continued power. Here a key focus is on the changing forms of welfare governance as they impact on social policy and social work.

In the opening chapter, Chapter 1 on social policy and welfarism, David Gil places human needs as central to our understanding of social work practice in contemporary social welfare services as he attempts to unravel the origins, functions, and dynamics of social and global injustice and their manifestations in socially constructed ‘ill-fare’. Individual and social development and well-being depend crucially on the role of welfare services – and social work practice – in alleviating the destructive symptoms of social and global injustice.

In ‘theorising welfare’ in Chapter 2, Mimi Abramowitz discusses the rise of neoliberalism and its impact on the United States welfare state, the well-being of families, the delivery of human services, and social work. She argues that both the rise of the welfare state and the subsequent neoliberal effort to dismantle it were not accidental or simply political. Rather, they represent contrasting governmental responses to the two major economic crises of the 20th century: the Great Depression and economic recession in the mid-1970s. In charting the collapse of the US middle class and the transfer of wealth to the already wealthy, she points out that the Global Economic Crisis is not just another financial downturn, but that the USA could be facing a systemic crisis of capitalism that is only resolved through major restructuring of the political economy. The chapter examines the dynamics of these shifts and the way in which neoliberalism has placed the well-being of families, effective human services, and social work values in jeopardy.

In Chapter 3, Robert Fairbanks examines how the transformation from a Keynesian–Fordist welfare state to a post-Keynesian – ‘post-welfare’ – regime of capitalist accumulation articulates with the proliferation of (potentially) novel forms of welfare governance in the complex and contradictory post-welfare moment. Though there is some general consensus on the extent to which neoliberalism is characterised by – and indeed perhaps even makes a virtue of – unevenness across institutional, economic, and political contexts, there are still important disagreements about its historical significance for the question of welfare governance and social regulation. Fairbanks traces the concept of regulation from its Victorian-era antecedents in civil society, to its national form in the welfarist era and its market form in the post-welfare era to delineate the analytical traditions of political economy and governmentality in welfare state theory. He provides a framework for historically and geographically contingent analysis and criticism of contemporary welfare state transformation. He illustrates the ways in which variant welfare state forms – neoliberal, neocorporatist, neostatist, and neocommunitarian – have evolved from institutional legacies, the balance of political forces, and the changing economic and political conjunctures in which different strategies are pursued.

Sanford Schram revisits Mark Lipsky’s pathbreaking ideas about ‘welfare professionals and street-level bureaucrats’ in Chapter 4 showing how work on the frontlines of welfare bureaucracies has been changing, often quite dramatically, and how workers’ discretion in the current era is, as in the past, often regarded as part of the problem, while also seen as necessary to accomplish public policy goals. He focuses on the changing environment in which these enduring challenges occur; the changed nature of frontline worker discretion in an era of auditing systems that facilitate greater surveillance of worker actions; and the changing nature of welfare organisations, now often contract agencies, with their own hiring standards, procedures, and performance pressures related to contract renewal. Even under these flexible, short term labour hiring regimes highlights how workers still need to have discretion in order to perform their jobs effectively. Since their discretion is frequently treated as problematic, it is still constrained by various management stratagems, if in new ways. Lastly, he highlights how the issue of frontline discretion is affected by the shift to ‘a neoliberal–paternalist regime’ of poverty governance in which the challenge is finding the right balance between managerial control and frontline discretion.

In Chapter 5, Mary Daly skilfully elaborates on the relationship between gender and welfare in contemporary societies. Both concepts are problematised, especially from the perspective of social change. Gender equality as an idea and political goal is subjected to critical scrutiny. Welfare, too, is a rather problematic concept, not least because in it are lodged complex issues about the well-being of individuals vis-à-vis that of collectivities, such as families and communities. The chapter focuses on key questions centring on how the relationship between gender and welfare is to be understood, especially in the context of changing gender roles and relations, and politics and policies instituted to address gender inequalities. The chapter engages with the mobilization of a progressive agenda for gender relations as it looks towards the future. Issues of individual autonomy arise as do matters of family, care, and equality.

In Chapter 6 on ‘welfare and social development’, James Midgley discusses the influential theory of social development, which builds on ideas of social and human capital in its aim to end the bifurcation of social welfare and economic development. Social development sees social policy as productivist and investment oriented and aims to foster a new conception of redistribution as social investment to harness the power of economic growth for social ends and to invest in people and enhance their capacity to participate in the productive economy. Midgley discusses ways in which social development works: through increasing the cost effectiveness of social welfare; enhancing human capital investments; promoting social capital formation; developing individual and community assets; facilitating economic participation through productive employment and self-employment; removing barriers to economic participation; and creating a social climate conducive to development. He argues that by enhancing social rights and promoting social justice, social development offers a new institutional policy alternative to social policy today.

REFERENCE

Piven, F.F., & Cloward, R. (2010). Relief, labour and civil disorder: An overview. In M. Gray & Webb, S.A. (eds). International social work, vol. 1. London: Sage.

1

Social Work, Social Policy, and Welfarism

Social work and welfarism evolved as societal responses to systemic social injustice and social-structural ‘ill-fare’. To understand social work and welfarism, one has, therefore, to unravel the origins, functions, and dynamics of social and global injustice and social ill-fare. To do so, this chapter examines the following:

1 | human needs as a frame of reference for individual and social development, well-being, and social and global justice; |

2 | meanings of social and global justice; |

3 | socially just communities and human nature; |

4 | universal dimensions of social policy systems; |

5 | emergence and spread of social injustice through coercive, undemocratic processes from local to global levels: oppression, domination, and exploitation; |

6 | economic systems, social justice, and social injustice; |

7 | welfarism and social work; and |

8 | social justice model of social work. |

HUMAN NEEDS, INDIVIDUAL AND SOCIAL DEVELOPMENT, WELL-BEING, AND SOCIAL JUSTICE

Like all living beings, humans tend to grow and develop spontaneously, and to ‘fare well’ when they can meet universal, intrinsic needs in their natural and socially evolved environments. When a seed is put into the ground, the sun shines, the rains fall, and there are appropriate nutrients in the soil, the seed will unfold its innate potential spontaneously and become the plant it is inherently capable of becoming. Analogously, human beings whose real needs can be met in their natural and social environments will spontaneously unfold their rich potential and will become what they are inherently capable of becoming. And entire human societies evolving in environments conducive to the realisation of the innate needs, capabilities and potential of all their members will become fully developed, rich societies. Hence, it is necessary to identify the universal, intrinsic needs of the human species as a frame of reference for environments conducive to the full realisation of these needs and for the well-being or ‘well-faring’ of entire societies. Many scholars who have studied human needs tend to agree on the following set of inter-related needs (Fromm, 1955; Gil, 1973; Maslow, 1970).

1 | Biological-material needs: Stable provision of biological necessities; sexual satisfaction; and regular access to life-sustaining and enhancing goods and services, the types, quantity, and quality of which vary among different cultures and over time. |

2 | Social–psychological needs: Stable, meaningful social relations and a sense of belonging to a community, involving mutual respect, acceptance, affirmation, care and love, and opportunities for self-discovery and for the emergence of a positive self-identity. |

3 | Productive–creative needs: Meaningful participation, in accordance with one’s innate capacities and stage of development, in the productive activities of one’s community and society. |

4 | Security needs: A sense of trust and security emerging from the experience of steady fulfillment of one’s biological–material, social–psychological, and productive–creative needs. |

5 | Self-actualisation needs: Becoming what one is innately capable of becoming through creative productivity and self-expression. |

6 | Spiritual needs: Discovering and giving coherence to one’s existence in relation to people, nature, and the world along known, unknown, and ultimately unknowable dimensions. |

The way these inter-related human needs are expressed tends to change over time in different social contexts. Their substance and dynamics are, however, constant and universal. Human survival, development, and physical, emotional, and social health and well-being depend always on adequate levels of fulfillment of these basic human needs.

People’s subjective perceptions of their needs and interests result not only from becoming conscious of their basic, innate needs, but also from socialisation in particular societies with unique ways of life and socially constructed definitions of needs and interests. People’s actual perceptions of their needs and interests may, therefore, correspond to, overlap with, substitute for, or conflict with their basic needs and real interests. When perceived needs and interests do not overlap sufficiently with people’s basic needs and interests, socially defined substitutes (e.g., material wealth) may be realised, while basic needs (e.g., meaningful human relations) remain unfulfilled. Whether people correctly perceive their basic needs and interests, and can actually satisfy them in everyday life, depends on their natural environment and their socially evolved ways of life (i.e., the organisational systems of their societies). When these systems are just they are conducive to everyone’s need fulfillment. When they are unjust, fulfillment of real needs is unlikely.

MEANINGS OF SOCIAL AND GLOBAL JUSTICE

Many advocates of social justice do not specify their understanding of this concept. However, such specification is necessary for deliberations of strategies toward the realisation of social justice from local to global levels. This chapter, therefore, sketches an understanding of social justice on three related levels: individual human relations; social institutions and values; and global human relations (Gil, 2004).

Socially just human relations require equal acknowledgement and treatment of everyone as autonomous, authentic subjects with equal rights and responsibilities, rather than as objects to be used and exploited as is typically done in unjust human relations of the prevailing capitalist economic culture. This conception of social justice was foreshadowed in biblical and gospel sources, as illustrated by sayings such as ‘Love thy neighbour as thyself’. Similar ideas of social justice can be found in the Koran and in sacred scriptures of Buddhists, Hindus, Confucians, and other Asian, African, and (native) American traditions.

On the level of social institutions and values, social justice means socially established living conditions and ways of life conducive to the fulfillment of everyone’s intrinsic needs and the realisation of everyone’s innate potential, from local to global levels. Socially just societies, whenever and wherever they existed throughout history, have been egalitarian, structurally nonviolent, and genuinely democratic (Kanter, 1972; Kropotkin, 1956). ‘Egalitarian’ as used here is not a mathematical but a social–philosophical notion (Tawney, 1931). It means all people have equal rights, responsibilities, and opportunities in all spheres of life, including control of resources; organisation of work; distribution of goods, services, and rights; governance; and social reproduction. ‘Equality’ does not mean everything is divided and distributed in identical shares but distributions are geared thoughtfully to individual differences and everyone’s needs are acknowledged equally.

Socially just societies do not require ‘structural violence’ by the state, as socially unjust societies do (Gil, 1996) and they tend to practice genuine, rather than merely ritualistic, ‘ballot-box’ democracy. In the context of social, economic, and political equality of socially just societies, no individuals, groups, or social classes can monopolise power over other people and the state by using accumulated wealth to influence the outcome of elections as is usually done in unjust societies.

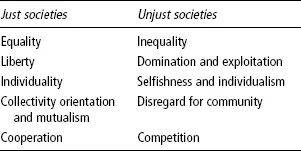

Values are guidelines which people evolved in the course of social evolution to differentiate behaviours whose outcomes they valued and which they, therefore, considered worthy of repetition, from behaviours whose outcomes they disliked and which they, therefore, believed should be avoided. The frame of reference for what is good and valued, and what is evil and not valued, are the real and perceived needs and interests of those who judge behavioural outcomes, usually dominant groups of societies (Gil, 1992). Table 1.1 shows the value dimensions differentiating socially just from socially unjust societies.

Table 1.1 Value dimensions

Social justice on a scale of global ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Editors and Contributors

- INTRODUCTION

- SECTION 1 WELFARE, SOCIAL POLICY, AND SOCIAL WORK

- SECTION 2 SOCIAL WORK PERSPECTIVES

- SECTION 3 SOCIAL WORK PRACTICE

- SECTION 4 SOCIAL WORK VALUES AND ETHICS

- SECTION 5 SOCIAL WORK RESEARCH

- SECTION 6 SOCIAL WORK IN CONTEXT

- SECTION 7 FUTURE CHALLENGES FOR SOCIAL WORK

- Index