![]()

1

Social Research and Data Analysis: Demystifying Basic Concepts

Introduction

This book is about the analysis of certain kinds of data, that is, only quantitative data. We need to begin by discussing the three concepts that make up the main title of this book. The core concept is ‘data’. On the surface, it appears to be a simple and unproblematic idea. However, lurking behind it are complex and controversial philosophical and methodological issues that need to be considered. This concept is qualified by the adjective ‘quantitative’, thus indicating that only one of the two main types of data in the social sciences will be discussed. Just what constitutes ‘quantitative’ data will be clarified. The purpose of the book is to discuss methods of ‘analysis’ used in the social sciences, methods by which research questions can be answered. The variety of methods that are available for basic analysis will be reviewed.

This chapter deals with three fundamental questions:

- What is the purpose of social research?

- What are data?

- What is data analysis?

The chapter begins with a discussion of the role of research objectives, research questions and hypotheses in achieving the purpose of research. This is followed by a consideration of the relationship between social reality and the data we collect, and of the types and forms of these data. Included is a discussion of ‘concepts’ and ‘variables’, the ways in which concepts can be measured, and the four levels of measurement. The chapter concludes with a review of the four main types of data analysis that are covered in subsequent chapters.1 Let us start with the first question.

What is the Purpose of Social Research?

The aim of all scientific disciplines is to advance knowledge in their field, to provide new or better understanding of certain phenomena, to solve intellectual puzzles and/or to solve practical problems. Therefore, the critical issues for any discipline are the following:

- What constitutes scientific knowledge?

- How does scientific knowledge differ from other forms of knowledge?

- How do we judge the status of this knowledge? With what criteria?

- How do we produce new knowledge or improve existing knowledge?

In order to solve both intellectual and practical puzzles, researchers have to answer questions about what is going on, why it is happening and, perhaps, how it could be different. Therefore, to solve puzzles it is necessary to pose and answer questions.

The Research Problem

A social research project needs to address a research problem. In order to do this, research questions have to be stated and research objectives defined; together they turn a research problem into something that can be investigated. Throughout this book the following research problem will be addressed: the apparent lack of concern about environmental issues among many people and the unwillingness of many to act responsibly with regard to these issues. This is a very broad problem. In order to make it researchable, it is necessary to formulate a few research questions that can be investigated. These questions will be elaborated in Chapter 2. In the meantime, to illustrate the present discussion, let us examine two of them here:

- To what extent is environmentally responsible behaviour practised?

- Why are there variations in the levels of environmentally responsible behaviour?

Each research question entails the pursuit of a particular research objective.

Research Objectives

One way to approach a research problem is through a set of research objectives. Social research can pursue many objectives. It can explore, describe, understand, explain, predict, change, evaluate or assess aspects of social phenomena.

- To explore is to attempt to develop an initial rough description or, possibly, an understanding of some social phenomenon.

- To describe is to provide a detailed account or the precise measurement and reporting of the characteristics of some population, group or phenomenon, including establishing regularities.

- To explain is to establish the elements, factors or mechanisms that are responsible for producing the state of or regularities in a social phenomenon.

- To understand is to establish reasons for particular social action, the occurrence of an event or the course of a social episode, these reasons being derived from the ones given by social actors.

- To predict is to use some established understanding or explanation of a phenomenon to postulate certain outcomes under particular conditions.

- To change is to intervene in a social situation by manipulating some aspects of it, or by assisting the participants to do so, preferably on the basis of established understanding or explanation.

- To evaluate is to monitor social intervention programmes to assess whether they have achieved their desired outcomes, and to assist with problem solving and policy-making.

- To assess social impacts is to identify the likely social and cultural consequences of planned projects, technological change or policy actions on social structures, social processes and/or people.

The first five objectives are characteristic of basic research, while the last three are likely to be associated with applied research. Both types of social research deal with problems: basic research with theoretical problems, and applied research with social or practical problems. Basic research is concerned with advancing fundamental knowledge about the social world, in particular with description and the development and testing of theories. Applied research is concerned with practical outcomes, with trying to solve some practical problem, with helping practitioners accomplish tasks, and with the development and implementation of policy. Frequently, the results of applied research are required immediately, while basic research usually has a longer time frame.

A research project may pursue just one of these objectives or perhaps a combination of them. In the latter case, the objectives are likely to follow a sequence. For example, the four research objectives of exploration, description, explanation and prediction can occur as a sequence in terms of both the stages and the increasing complexity of research. Exploration may be necessary to provide clues about the patterns that need to be described in a particular phenomenon. Exploration usually precedes description, and description is necessary before explanation or prediction can be attempted. Whether all four objectives are pursued in a particular research project will depend on the nature of the research problem, the circumstances and the state of knowledge in the field.

The core of all social research is the sequence that begins with the description of characteristics and patterns in social phenomena and is followed by an explanation of why they occur. Descriptions of what is happening lead to questions or puzzles about why it is happening, and this calls for an explanation or some kind of understanding. The two research questions stated in the previous subsection illustrate these two research objectives. To be able to explain why people differ in their level of environmentally responsible behaviour, we need to first describe the range in levels of this behaviour. The first question is concerned with description and the second with explanation.

Research Questions

To pursue such objectives, social researchers need to pose research questions. Research questions define the nature and scope of a research project. They:

- focus the researcher’s attention on certain puzzles or issues;

- influence the scope and depth of the research;

- point towards certain research strategies and methods of data collection and analysis;

- set expectations for outcomes.

Research questions are of three main types: ‘what’ questions, ‘why’ questions and ‘how’ questions:

- ‘What’ questions seek descriptive answers.

- ‘Why’ questions seek understanding or explanation.

- ‘How’ questions seek appropriate interventions to bring about change.

All research questions can and perhaps should be stated as one of these three types. To do so helps to make the intentions of the research clear. It is possible to formulate questions using different words, such as, ‘who’, ‘when’, ‘where’, ‘which’, ‘how many’ or ‘how much’. While questions that begin with such words may appear to have different intentions, they are all versions of a ‘what’ question: ‘What individuals …’, ‘At what time …’, ‘At what place …’, ‘In what situations …’, ‘In what proportion …’ and ‘To what extent …’. Similarly, some questions that begin with ‘what’ are actually ‘why’ questions. For example, ‘What makes people behave this way?’ seeks an explanation rather than description. It needs to be reworded as: ‘Why do people behave this way?’.

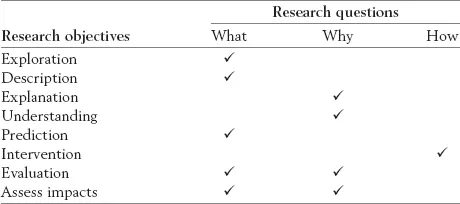

Each research objective requires the use of a particular type of research question or, in a few cases, two types of questions. Most research objectives require ‘what’ questions: exploration, description, prediction, evaluation and impact assessment. It is only the objectives of understanding and explanation, and possibly evaluation and impact assessment, that require ‘why’ questions. ‘How’ questions are only used with the objective of change (see Table 1.1). Returning to our two research questions, the first is a ‘what’ question that seeks a descriptive answer, and the second is a ‘why’ question that asks for an explanation.

The Role of Hypotheses

It is a commonly held view that research should be directed towards testing hypotheses. While some types of social research involve the use of hypotheses, in a great deal of it hypotheses are either unnecessary or inappropriate. Clearly stated, hypotheses can be extremely useful in helping to find answers to ‘why’ questions. In fact, it is difficult to answer a ‘why’ question without having some ideas about where to look for the answer. Hence, hypotheses provide possible answers to ‘why’ questions.

Table 1.1 Research questions and objectives

In some types of research, hypotheses are developed at the outset to give this direction; in other types of research, the hypotheses may evolve as the research proceeds. When research starts out with one or more hypotheses, they should ideally be derived from a theory of some kind, preferably expressed in the form of a set of propositions. Hypotheses that are plucked out of thin air, or are just based on hunches, usually make limited contributions to the development of knowledge because they are unlikely to connect with the existing state of knowledge.

Hypotheses are normally not required to answer ‘what’ questions. Because ‘what’ questions seek descriptions, they can be answered in a relatively straightforward way by collecting relevant data. For example, a question such as ‘What is the extent of recycling behaviour among university students?’ requires specification of what behaviour will be included under ‘recycling’ and how it will be measured. While previous research and even theory may help us decide what behaviour is relevant to this concept, there is no need to hypothesize about the extent of this behaviour in advance of the research being undertaken. The data that are collected will answer the question. On the other hand, to answer the question ‘Why are some students regular recyclers?’ it would be helpful to have a possible answer to test, that is, a hypothesis.

This theoretical use of hypotheses should not be confused with their statistical use. The latter tends to dominate books on research methods and statistics. As we shall see later, a great deal of research is conducted using samples that are drawn from much larger populations. There are many practical benefits in doing this. If such samples are drawn using statistically random procedures, and if the response rate is very high, a researcher may want to generalize the results found in a sample to the population from which the sample was drawn. Statistical hypotheses perform a role in this generalization process, in making decisions about whether the characteristics, differences or relationships found in a sample can be expected to also exist in the population. Such hypotheses are not derived from theory and are not tentative answers to research questions. Their function is purely statistical. When research is conducted on a population or a non-random sample, there is no role for statistical hypotheses. However, theoretical hypotheses are relevant in any research that requires ‘why’ questions to be answered.

What are Data?

In the context of social research, the concept of data is generally treated as being unproblematic. It is rare to find the concept defined and even rarer to encounter any philosophical consideration of its meaning and role in research. Data are simply regarded as something we collect and analyze in order to arrive at research conclusions.

The concept is frequently equated with the notion of ‘empirical evidence’, that is, the products of systematic ‘observations’ made through the use of the human senses. Of course, in social research, observations are made mainly through the use of sight and hearing.

The concept of observation is used here in its philosophical sense, that is, as referring to the use of the human senses to produce ‘evidence’ about the ‘empirical’ world. This meaning needs to be distinguished from the more specific usage in social research where it refers to methods of data collection that use the sense of sight. In this latter method, ‘looking’ is distinguished from other major research activities such as ‘listening’, ‘conversing’, ‘participating’, ‘experiencing’, ‘reading’ and ‘counting’. All of these activities are involved in the philosophical meaning of ‘observing’.

Observations in all sciences are also made with the use of instruments, devices that extend the human senses and increase their precision. For example, a thermometer can measure temperature far more precisely and consistently than can the human sense of touch. Its construction is based on notions of hot and cold, more and less, and of an equal interval scale. In short, it has built into it many assumptions and technical ideas that are used to extend differences that can be experienced by touch. Similarly, an attitude scale, consisting of an integrated set of statements to which responses are made, provides a more precise and consistent measure than, say, listening to individuals discussing some issue.

The notion of empirical evidence is not as simple as it might seem. It entails complex philosophical ideas that have been vigorously contested. These disagreements centre on different claims that are made about:

- what can be observed;

- what is involved in the act of observing;

- how observations are recorded;

- what kinds of analysis can be done on them; and

- what the products of these observations mean.

There are a number of important and related issues involved in the act of observing. One concerns assumptions that are made about what it is that we observe. A second issue has to do with the act of observing, with the connection between what impinges on the human senses and what it is that produces those impressions. A third issue is...