![]()

1

What This Book is About

Introduction

In an article entitled ‘Self-esteem: the kindly apocalypse’, the writer (a philosopher) recalled a conference he had attended. At the end of the presentation, questions were invited from the audience:

The speaker responded to the first question at the end by saying, ‘That’s a very fine question, a really interesting and important question’. It had seemed to me a fairly straightforward question, and I puzzled over why he thought it so significant. But this was intellectual energy wasted: every question, it turned out, was interesting, important, truly insightful or a question the speaker was enormously grateful had been asked. (Smith, 2002, pp. 92–3)

The writer went on to argue that this is a kind of dishonesty, albeit probably practised for benign reasons. Many who work in education will recognise the scenario, undoubtedly mirrored in countless classrooms and lecture theatres. Most will understand the reasons for the speaker’s approach. It is possible that some may also share a sense of unease that there is something less than honest about this approach. If so, this book may help to overcome that sense of unease.

This book has been written for student teachers, their tutors and teachers in primary classrooms. However, as you read, it may become apparent that the main issues, the underlying theories, and many of the techniques described are relevant to those who work in other sectors too. In fact, having read this book, you may arrive at the conclusion that the material applies to individuals in many contexts, and at all stages of life. This is certainly the feedback we have had when presenting our work at conferences and in-service sessions.

Essentially, our aim is to provide advice about how to enhance the self-esteem of children. But it is not just a catalogue of tips for teachers to try out in their classes. Certainly, advice on strategies and techniques makes up a significant proportion of the content, but the book is about more than this. In order to intervene effectively in the classroom, theoretical understanding is essential. It is difficult to see how someone can effectively enhance self-esteem in the classroom without a sound understanding of its fundamental structure, how it is influenced and why certain techniques are more likely than others to help children. Accordingly, the early chapters provide a summary and analysis of the key theoretical and empirical work in the area. This includes examining what we mean by self-esteem, exploring some basic theoretical ideas, and reflecting on the messages we may safely take from the research in this area. This process may encourage you to rethink some of your own attitudes – or it may reinforce your current beliefs. In either case, it should empower you to develop your practice with a clear sense of direction – and with increased confidence.

Why another book on self-esteem?

The fact that you are reading this presupposes that you have a particular interest in self-esteem – or a particular purpose behind learning about the key messages in the book. It may be that you have been asked to read it for some course work, or that you are looking to update your knowledge in this area. In terms of your own attitudes, you may be approaching the content firmly committed to the belief that self-esteem enhancement is an important part of the teacher’s role. But, equally, you may be flicking through the pages with a more sceptical eye; you may wonder what another book on this topic can add to an aspect of school life which already receives much attention. In terms of practice, you may be interested in adding to your repertoire of enhancement techniques – or you may be critical of what is currently being done in the name of self-esteem in schools. Of course, these last two perspectives are not mutually exclusive; one can be committed to enhancing self-esteem but at the same time hold reservations about some aspects of current practice. Whether one of these perspectives – or some other – reflects your own position, we believe there will be issues in here which will stimulate personal as well as professional reflection.

Indeed, one might reasonably ask, why do we need another book on the subject? We believe there are several good reasons. As we explain in more detail later, one reason is that much of what we believe about self-esteem is not supported by research evidence. To take just one such example: there is an assumption made by many teachers that improving the overall self-esteem of children results in academic gains. While many who read this may be able to provide examples of individual cases where this appeared to be true, the uncomfortable fact is that there is little ‘hard’ research evidence to support such a belief. Several comprehensive and well-respected reviews of the literature have arrived at this conclusion, and the message has been picked up by many who have subsequently used it (and misused it) for their own purposes. However, as in many areas of social research, the issues here are contested, and the picture is not a straightforward one. Although the links between overall self-esteem and school performance are neither strong nor consistent, there is clear evidence of a relationship between more specific aspects of self-esteem and the related areas of academic performance. As professionals, a challenge for us is to reconcile apparently conflicting messages and decide what the evidence really does tell us. Chapters 2, 3 and 4 should help in this process.

A second reason why a new book is necessary follows on from this point. There exist several different research paradigms in this area – that is, different ways of conceptualising and investigating self-esteem. The field is characterised by different groups of researchers investigating different aspects of self-perceptions, using different methods – and, it has to be acknowledged, rarely referring to the work of the other groups. Sometimes different writers use different terminology for what appears to be the same phenomenon; one example is the way in which self-concept and global self-esteem are seen to be synonymous by some writers. Others differentiate these terms – but not consistently. On the other hand, sometimes different writers use the same terms – but with different meanings – and this can be even more confusing. An important example here is the use of the term self-worth; some use it interchangeably with self-esteem, while for others (including ourselves) it has a more specific meaning.

So, the language is not always shared, and one does not have to read many texts in this area before a realisation dawns that the area of self-perception is complex. If the literature is not exactly disparate, it certainly lacks consensus in many key areas. So where does this leave the committed (but busy) teacher and student teacher, keen to make sense of the topic – and keen to make a difference in the classroom? Well, if some of the messages above may be perplexing, and even disheartening, there is good news to follow. There is one model of self-esteem which is gaining currency – and which has some important benefits to offer us. One of these benefits is that the model is capable of incorporating the main ideas of the key writers in this complex area; it does so in a convincing manner, and in a way which is able to explain previous research findings. What is more, the messages that emerge have particular relevance for teachers; they resonate with their experiences and seem intuitively ‘right’. They also serve to direct classroom practice. This approach, known as a two-dimensional model of self-esteem, will be explained and analysed in some detail. It will be central to the strategies outlined in later chapters.

For a third reason, we might add the suspicion (let us call it no more than that) that some practices carried out in the name of self-esteem enhancement may be of doubtful value. There is a feeling in some quarters that certain techniques do little to develop genuine self-esteem, and indeed may have potentially undesirable consequences. Examples here include the emphasis on activities to make every child ‘special’, creating a no-blame culture, adhering to the principle that no one should be allowed to fail a task, and the over-use of praise. While such practices are frequently justified in relation to educational aims, some might not stand up to critical scrutiny. At the very least, it might be worth asking whether in practice there are some disadvantages to them.

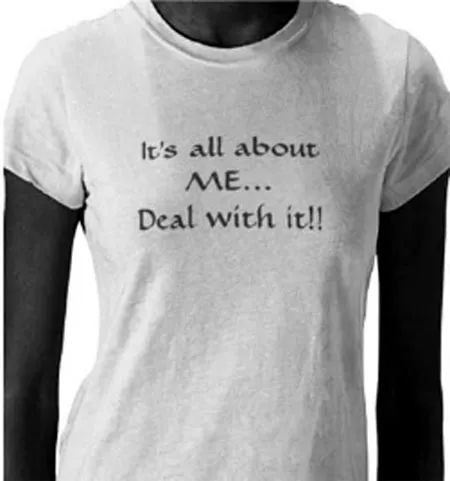

Figure 1.1 ‘So, is there a problem?’ Reproduced with permission from Lia Monforte, Fashionhut.net

The self-esteem backlash

There can be little doubt that such concerns have helped to fuel what has been called the self-esteem backlash. Several prominent academics, politicians and social commentators have attacked the emphasis on self-esteem enhancement in schools, and particularly what they see as frivolous or ill-advised practices. These criticisms will be examined in more detail later, but a key message from such writers is that our attempts to protect children from failure and make them ‘special’ are often at the expense of genuine learning and real personal growth. It is not difficult to appreciate the good intentions behind policies that try to ensure there is no failure in school: no wrong answers (no crosses or red pen), making everyone a winner, playing games on a no-score basis, and ensuring that at award ceremonies everyone gets a prize. However, it might be a mistake to ignore the possibility that such practices may also have a downside. According to some commentators, they may contribute to underachievement, a failure to cope with challenge and children who lack determination and resilience. We look in more detail at these issues in Chapter 4.

As the preceding paragraphs illustrate only too clearly, one of the most notable characteristics of the whole area of self-esteem is the polarisation of views. At the risk of resorting to caricatures, on the one hand we have those who see self-esteem as a panacea, who argue it is impossible to have too much self-esteem, and who would set it as the main purpose of education. On the other, we have the critics who assert that self-esteem policies have produced individuals who are boastful and self-obsessed; they are more likely to deny their faults, or make excuses for their poor performance and behaviour, than try to improve them. Thoughtful readers (including, we suspect, most experienced teachers) know that between these extremes there is an alternative perspective on self-esteem.

A positive but realistic perspective on self-esteem acknowledges that while there may be dangers with artificially inflated self-esteem, there are many more serious problems associated with low self-esteem. These problems influence children’s learning but, equally importantly, they may have serious consequences for their personal and social lives. Although we have explained above that many beliefs in relation to self-esteem are contested, there is a general consensus that low-self-esteem individuals tend to underachieve, be more at risk from a range of social and personal ills and tend to live less fulfilling lives. We suspect many who enter the teaching profession need no more justification than this to target self-esteem as an educational goal.

However, the key point here is that the aim of a meaningful self-esteem enhancement programme is not to artificially inflate self-esteem with a range of superficially appealing techniques (often pedalled by those with a financial interest in so doing). Instead it is to use sound knowledge about the structure of self-esteem and the processes of enhancement to help children to develop a healthy and realistic sense of self. Stated simply, a healthy self-esteem involves recognition of our positive qualities and an acceptance of our less-positive ones. It is this perspective which guides what you will read in this book.

To conclude this section: if the landscape of self-esteem is both confused and confusing, where does this leave teachers who want to gain a clear picture in order to help their pupils? Well, despite the uncertainties and some unpromising messages that emerge in this area, the good news is that most caring teachers retain an interest in the self-esteem of their pupils. Their convictions, often formed in the light of experience, lead them to believe that in genuine self-esteem we have something important – something that is worth persevering with. We hope this book will help the reader to avoid the distortions produced by the wrong kind of emphasis on self-esteem, while giving them the knowledge they need to help develop in pupils a realistic and positive sense of self.

What then are the key ideas we work with?

We will start with the nature of self-esteem – its fundamental structure and how it is influenced by life experiences. In everyday language, we tend to share a common understanding about what we mean by self-esteem; however, when we come to define it, things are not so straightforward. In fact, despite being an enduring construct in psychological theory (for more than a century), the wide variety of definitions, models and measures highlights a lack of consensus amongst workers in the area. We examine some of these differing definitions and models, and show how an alternative model is capable of incorporating the differing perspectives and explaining the varying research findings in the field. That model emphasises that how we feel about ourselves involves two separate judgements: how worthwhile do I feel, and how competent am I to tackle the challenges I face? It is known as the two-dimensional model of self-esteem.

Since self-esteem is a dynamic construct, it is necessary to understand the processes involved in its formation and modification. We look at a series of questions in relation to this. What are the factors that influence a sense of self-worth? What sort of experiences help to create – or damage – self-competence? To what extent are these processes influenced by others? These are important questions which we need to answer if we are to understand the growth process. Of course, as teachers, a fundamental issue is what we can – and should – do to enhance the self-esteem of our pupils. Central to the discussion here will be the clear messages which emerge from the two-dimensional model of self-esteem. Viewing classroom interactions from this perspective provides us with a clear set of guiding principles, and helps to inform strategies and techniques.

As indicated above, some practices have developed in primary schools in the past in the name of self-esteem enhancement which many believe may be questioned. One of the reasons for this is that such self-esteem activities were seen as taking time away from the ‘important’ work of the classroom: learning in the core subjects. In contrast, many of the strategies we describe in the later chapters of this book allow teachers to enhance the self-esteem of children while at the same time improving their learning. That is, the techniques become part of the teacher’s day-to-day teaching in the core subjects. One of the advantages of this approach is that it counters one of the key criticisms of the anti-self-esteem lobby; we show that self-esteem enhancement does not have to be at the expense of core learning. This perspective can help to narrow what has become known as the self-esteem divide: the gap that exists between those who see themselves as primarily responsible for teaching knowledge and skills, and those who see a broader role in terms of helping to support the personal and social development of the child. As should become clear as you read the book, many of the processes described have relevance to both groups of teachers.

It will be possible for those interested mainly in classroom techniques to start reading this book from Chapter 5 onwards, but we would encourage readers not to skip the theoretical sections in Chapters 2, 3 and 4. We say this for three reasons. First, it is generally accepted that knowledge of theory is important to help understanding, and move beyond the model of teacher as technician. In our pre-service work with teaching students and continuing professional development (CPD) work with experienced practitioners, we have witnessed many ‘Aha!’ moments, with individuals explaining that the theoretical ideas we described had helped them to understand the behaviour and mindsets of children (and other adults) they had met. Understanding and believing in the fundamental structure is an important step in developing classroom practice. Second, at a practical level, the theoretical understanding provides a lens through which to view classroom interactions. In a contested and complex area, it provides a clear conceptual model which allows analysis of events, and points towards productive courses of action. It helps us to see the wood as well as the trees. And third, it allows extrapolation. Our list of techniques and strategies is not exhaustive, and understanding the main principles allows readers to develop ideas of their own, tailored to their own pupils in their own school contexts.

An overview of the chapters

Following this introduction, Chapter 2 will provide a general overview of research and theory in the area, and summarise the key messages that emerge. We look at the way in which self-esteem has been conceptualised, and in the process consider several other self-referent terms – many of which are used interchangeably. We provide an overview of the dominant approaches to the study of self-esteem: the unidimensional model, where self-esteem is primarily seen as an attitude towards the self, a development of this in the form of a multi-dimensional model and finally a more complex hierarchical model, which is based on a set of differentiated and hierarchical relationships. We shall look at some key messages from the literature in these areas. In the course of this chapter, we shall also look at the debate around what some writers call the contingencies of self-esteem. These are the factors on which we stake our self-esteem and, simply stated, if we value a particular characteristic, our self-judgements in that area become more important to our self-esteem. However, in contrast, some writers argue that this ‘importance effect’ is not significant in determining levels of self-esteem. Effectively, your performance affects your self-esteem, whether you care about it or not. A...