![]()

Background to the Science of Environmental Change

John A. Matthews, Patrick J. Bartlein, Keith R. Briffa, Alastair G. Dawson, Anne De Vernal, Tim Denham, Sherilyn C. Fritz and Frank Oldfield

This chapter has two main aims. First, it sets the scene for the Handbook by addressing three fundamental questions about environmental change. (1) What exactly is meant by the term ‘environmental change’? (2) Why precisely is knowledge and understanding of environmental change so important to science and to society? And (3) what have been the main milestones and paradigms in the development of the field? The second aim is to outline the organisation of the Handbook, which attempts to provide, in two volumes, comprehensive coverage of the present state of scientific knowledge and understanding of environmental change while emphasising current priorities and trajectories of research.

| 2 | DEFINING ENVIRONMENTAL CHANGE |

The term environmental change means different things to different people. In this Handbook, use of the term is not limited simply to the relatively recent changes in aspects of the environment that affect, or are affected by, the human population. Instead, the primary concern is with the science of environmental change sensu lato based on the following broad definition: the study of changes in the geo-ecosphere, together with their actual and potential interactions with people.

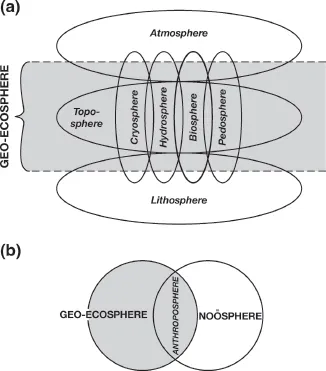

The concept of an Earth ‘sphere’ was first introduced by Suess (1875) in the context of the geological evolution of the European Alps. The geo-ecosphere, or global geoecosystem, is a relatively new concept that encompasses the several individual spheres – atmosphere, hydrosphere, cryosphere, lithosphere, biosphere, pedosphere, and so on – that are commonly identified as interacting components of the biophysical (or natural) environment at the Earth’s surface (Figure 1.1a). The term geo-ecosphere is preferred to ecosphere, because it gives greater weight to the physical systems in their own right, rather than merely the non-living components that interact with the biosphere (cf. Huggett, 1999).

Figure 1.1 Earth spheres, the arena of environmental change: (a) the geoecosphere and its component ‘spheres’; (b) the human-influenced geoecosphere, or anthroposphere.

Source: Matthews and Herbert (2008).

There may not be universal agreement on use of the term geo-ecosphere for our object of study but it reflects well the recent recognition of the need for integration of the various disciplines involved in the study of the changing environments of the Earth. This need has been widely recognised in the Earth sciences, for example, by the formation of the relatively new Biogeosciences Section of the American Geophysical Union (AGU) and the similar Biogeosciences Division of the European Geosciences Union (EGU). The Biogeosciences Section of the AGU emphasises the biological aspects of the Earth sciences, especially biogeochemistry, biogeophysics and planetary ecosystems. Indeed, its goal is to address better the interactions of humans with climate, hydrology and ecosystems, and to provide a scientific forum for environmental policy (http://www.agu.org/sections/biogeo/index.html).

Interactions with people are introduced in Figure 1.1b, which defines the anthroposphere as the ‘human-influenced geo-ecosphere’. Several terms have been used for the human sphere itself: here we use the term noösphere for the sphere of influence of the human mind (Samson and Pitt, 1999; Teilhard de Chardin, 1956; Vernadsky, 1945). The noösphere therefore includes human thoughts, opinions, actions and policies relating to environmental change, whereas the anthroposphere may be considered as carrying the biophysical imprint of these human dimensions of environmental change. Changes in any or all of the ‘spheres’ within both the natural geo-ecosphere and anthroposphere are parts of environmental change according to our definition. Because of the extent and complexity of the interactions between the various spheres, much environmental change research is now viewed as part of Earth system science. This focuses on the geoecosphere and anthroposphere as a whole rather than on the component parts (see later section on the development of Earth system science). Of particular importance is interdisciplinary research on process interactions and the dynamics of the geo-ecosphere, coevolution of the physical landscape and the biosphere, and likely future change (cf. National Research Council, 2010). The human dimensions of environmental change are increasingly important, as is made clear below, but there are other dimensions that need to be considered.

Timescales and spatial scale need to be taken into account in any consideration of environmental change. The study of environmental change includes investigating changes of the geological, archaeological and historical past, and those that may happen in the future, on various timescales. Some changes, such as those associated with continental drift and evolution, may take millions of years and, for much of the time, have proceeded without being influenced by people. Other changes in the geological record, such as those associated with the onset or termination of stadials and interstadials, may have occurred within a decade or less, and some of these abrupt changes also occurred long before the human species evolved (National Research Council, 2002).

In relation to spatial scale, environmental changes range from local, through regional, to global and, in the future, will affect different places on Earth in different ways: from polar ice sheets to tropical rain forests, and from the highest zones of terrestrial mountains to the deepest marine environments. The term ‘global environmental change’ has been used in a variety of ways (Goudie, 2009). Here a geocentric definition is offered, based on Turner et al. (1990a), as ‘any natural or anthropogenic environmental change that affects a global-scale biophysical system (a systemic global change) or the effects of which become global in extent (a cumulative global change)’. Systemic global changes include the climatic effects of major volcanic eruptions, enhanced emissions of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere from industrial sources, and changes to the oceanic circulation; cumulative global changes include deforestation and its effects, such as soil erosion and biodiversity loss.

Environmental change is, in many ways, a complex series of interacting processes and a bigger topic than merely those aspects impinging on humanity. The Handbook of Environmental Change reflects the broad and long view of the science of environmental change, while taking full account of the human dimensions. Some emphasis is given, however, to change in the recent past and the immediate future, where natural biophysical change interacts with human populations.

| 3 | SCIENTIFIC IMPORTANCE AND SOCIETAL RELEVANCE |

There are two basic reasons why knowledge and understanding of environmental change are so important: first, environmental change presents major scientific questions that stretch our curiosity to the limit; and second, it poses major practical problems for people and society and, particularly in relation to climate change, is arguably the most important issue facing humanity today.

Because most aspects of the environment evolve constantly, knowledge of environmental change is fundamental to understanding how the geo-ecosphere works. The most important scientific questions generally focus on the pattern, timing, causes and mechanisms of environmental change. These questions present huge challenges to science and to the human intellect.

Not least of these scientific challenges are the complexities of the interactions within the geo-ecosphere as an Earth system in which human populations, activities and effects are component parts. Most successes from the application of scientific method in the past have been based on the analysis of relatively simple systems using a reductionist approach (Pickett et al., 2007). Scientific methods appropriate to understanding ecosystems, geo-ecosystems and other holistic entities with their potential for complex interactions (Mitchell, 2009) and so-called emergent properties (Bedau and Humphreys, 2008), are at a comparatively early stage of development. So are the methods appropriate to those scientific fields with important temporal dimensions involving, for example, reconstructing and explaining past events (Inkpen and Wilson, 2009). Scientists asking questions about palaeoenvironmental or future events rarely have the opportunity to conduct classical experiments; but they can utilise natural experiments (Deevey, 1969; Diamond and Robinson, 2010) and computer modelling (Bartlein and Hostetler, 2004; Hargreaves and Annan, 2009; Knutti, 2008; Street-Perrott, 1991) to develop and test their hypotheses and conclusions. Furthermore, the human dimensions of environmental change research, such as explaining past human–environmental interaction, require cooperation between science, social science and the humanities, to develop hybrid methods of analysis and synthesis (see, e.g., Endfield, 2008; Head, 2000).

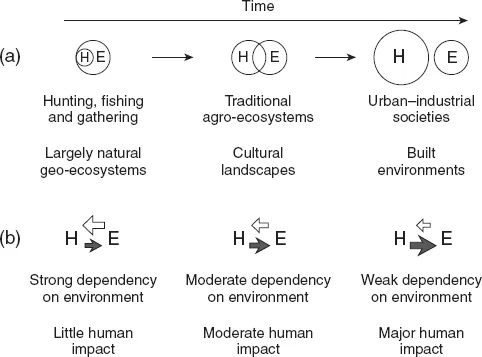

Many practical problems for society today stem from the fact that anthropogenic causes have become increasingly dominant over the natural causes of environmental change during the last c.11,500 years of the Holocene (Alverson et al., 2003; Messerli et al., 2000; Roberts, 1998; Simmons, 2008), during the last two or three hundred years of the Anthropocene (Crutzen and Stoermer, 2001), and especially during the last 60 years or so since the mid-twentieth century (McNeill, 2000; Oldfield, 2005; Steffen et al., 2004). From the mid-Holocene onwards, at first agricultural and later industrial societies, altered the nature of the interaction between people and the biophysical environment as their relative impact reversed (Figure 1.2). Hunter–gatherers lived within largely natural geo-ecosystems with a high level of dependency on their biophysical surroundings. Urban–industrial societies live farther apart from nature in built environments, and their relationship with the biophysical environment is dominated by major human impacts. Cultural landscapes, especially traditional agro-ecosystems, are intermediate in character. Cultural anthropologists identify similar patterns of interaction in the context of contemporary human societies with different economic systems and lifestyles (Crate and Nuttall, 2009; Peoples and Bailey, 2006).

The scale of human impact on the environment differs between the various Earth spheres, rates of change have varied through time, and there have been major differences in the nature and rate of impact at the regional scale (see, e.g., the major assessments of Goudie, 2007; Thomas, 1956; and Turner et al., 1990b). Nevertheless, through time, the systemic and cumulative effects have become greater and increasingly global, as human impacts altered not only the structure but also the processes of the geo-ecosphere, its energy flows and its biogeochemical cycles (Oldfield, 2008). These interventions sometimes had irreversible and disastrous consequences for people, but sometimes societies showed remarkable resilience in the face of both natural and anthropogenic environmental changes (Diamond, 2005; McAnany and Yoffee, 2010; Rolett and Diamond, 2004; Schwartz and Nichols, 2006; Tainter, 2006). The present and future state of the biophysical environment is increasingly dependent on this human impact and on the policies, in place or otherwise, to counter adverse impacts.

Figure 1.2 People-environment interaction during the Holocene: (a) the changing nature of the interactions between human populations (H) and the biophysical environment (E); and (b) the relative scale of the respective impacts.

Source: Roberts (1998).

Climate change in general and global warming in particular hold a special place in the catalogue of human impacts on the environment because the consequences for humanity could be more disastrous than was the case with any other previous impact. Until recently, the nature and scale of the human impact was in doubt (see, e.g., Idso, 1988). However, the scientific community is now almost unanimous in its belief in global warming and in the attribution of the cause to the anthropogenic enhancement of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere; it is also gaining confidence in the predicted impacts (World Meteorological Organisation, 2003; Arctic Climate Impact Assessment, 2004; IPCC, 2007a, 2007b). During the twentieth century this impact truly became ‘something new under the Sun’ (McNeill, 2000), but what to do about it, and how to adapt and mitigate the effects, is much less clear (IPCC, 2007c; Giddens, 2009; Lomborg, 2001, 2007; Stern, 2007). The cultural, social, political and ethical reasons for why people disagree about climate change and what to do about it (Hulme, 2009) are largely beyond the remit of this book but are clearly relevant to the actions that have been taken so far and will be taken in the future in relation to mitigation policies.

At the present time, despite the existence of the scientific and technological know-how to counteract most of the world’s problems associated with environmental change – such as deforestation, desertification, soil degradation, habitat and biodiversity loss, water pollution and global warming – countries in all states of development remain vulnerable to environmental change. In addition to these types of environmental change, extreme events with a purely geophysical origin cannot be neglected. The effects of the Boxing Day tsunami around the coast of the Indian Ocean in 2004, Hurricane Katrina in the southern US in 2005, the Haiti and Chilean earthquakes of 2010, and the Japanese earthquake and tsunami of 2011, demonstrate the vulnerability of human populations to extremes in various components of the Earth system, some of which may be linked to anthropogenic origins. Environmental variability from gradual climatic changes to natural hazards and extreme events has affected human societies in the past and will continue to do so in the future (e.g., Caseldine and Turney, 2009; de Menocal, 2001; Diaz and Murnane, 2008; Dillehay, 2002; Grattan, 2006; Torrence and Grattan, 2002). It is necessary, therefore, to understand fully all the dimensions of environmental change. This Handbook focuses on the scientific basis of that understanding: a companion volume (Pretty et al., 2007) focuses on the cultural, social, political and ethical factors that influence how that information is used. Clearly, the first requirement of any decision making is a clear understanding of the science behind the phenomenon of environm...