![]()

PART 1

Understanding

Part 1 comprises four chapters. The first lays the foundation for a general appreciation of the nature of child neglect and emotional abuse. This is followed by an examination of practice points raised by a number of public inquiries and serious case reviews. Subsequently, there are two chapters which explore how neglect and emotional abuse might impact on children’s development.

![]()

1

Definitions and the roots of oppression

This introductory chapter outlines some of the concepts and models which can assist in an understanding of neglect and emotional abuse.

Chapter overview

• Terminology

• Rationale

• Cosmological model of children’s development

• Defining neglect and emotional abuse

• Roots of oppression and abuse

• Carer behaviour constituting neglect and emotional abuse

Terminology

In much of the literature, commentators use various alternatives to the term ‘emotional abuse’ and, as Navarre (1987) observed, ‘in professional literature the terms “psychological abuse’’, “emotional abuse” and “mental cruelty” have been used interchangeably’ (p. 45). Therefore, we include under the phrase ‘emotional abuse’ all terms such as ‘emotional’, ‘psychological’ or ‘mental’ combined with a word indicating some form of mistreatment such as ‘abuse’, ‘maltreatment’, ‘cruelty’ or ‘neglect’.

We have attempted throughout to refer to individuals with respect and to use terminology which recognises the worth and value of people, whether children or adults. However, we appreciate that terms which are currently acceptable might change and acquire connotations which are denigrating or discriminatory. We also know that different interest groups have alternative claims to terminology. Hague et al. (2011, p. 150), for example, assert that the term person ‘with disabilities’ is regarded as poor practice in the UK and, instead, the term ‘disabled’ person is used. Yet others prefer ‘child/person with disabilities’ because such phraseology emphasises the individual first and the disability or impairment second (e.g. Costantino, 2010). We also prefer ‘with disability’ rather than ‘disabled person’ because we believe that any apparent physical deficiency depends on environment and context. Therefore we use the term ‘with disabilities’ to refer to a state in a particular environment or context where aspects of the body have some functional limitation.

The word ‘case’ is frequently used throughout the book. Unlike the use of ‘case’ to describe a specific individual, it is employed as a synonym for ‘instance’. It is a convenient generic word to encompass a situation and might refer to an organisation, a family system or the name of a child. We know that some people object to the word ‘case’ but trying to avoid it makes expressions far too unwieldy.

Clearly we cannot meet everyone’s claim to the proper use of terms, nor can we anticipate the unknown. Therefore, we ask readers to substitute their preferred terms for any that do not fit with their philosophy or culture, or ones that become, at some point in the future, unacceptable.

Rationale

The first question we need to address is: Why write a book on child abuse and exclude physical and sexual abuse? Very many children suffer from all forms of abuse, and in still more instances there is physical assault or sexual exploitation committed against a background of neglect and emotional abuse. Our reply is, first, because physical and sexual abuse often dominate the general discourse on child protection, consequently, neglect and emotional abuse are all the more readily overlooked.

Furthermore, because the images of physical and sexual abuse are so powerful, it is difficult to read a book about general child abuse without the pictures of children like Victoria Climbié (Laming, 2003) seeping into our consciousness. Consequently, many of the key issues relating to physical abuse are inescapably addressed in general books on child abuse. Additionally, there are a plethora of works devoted explicitly to sexual abuse which only incidentally deal with neglect and emotional abuse.

An additional rationale for examining neglect and emotional abuse in detail is that these can be a precursor to physical and sexual abuse. For example, Peter Connelly, who was killed in 2007, began to be seriously physically abused after the boyfriend of Peter’s mother became involved in the family. However, prior to this, his mother was described as ‘an extraordinarily neglectful parent’ (Jones, 2010, p. 59). Accurate, timely recognition of neglect and emotional abuse, followed by appropriate, supportive intervention, can prevent an escalation of mistreatment.

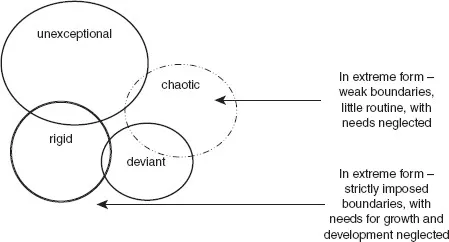

Families and institutions may reflect the dynamics of one of four types illustrated in Figure 1.1. These are not stringent categories and need to be viewed within the context of cultural mores. For example, a Victorian boarding-school, which might have been considered ‘unexceptional’ in late nineteenth-century Britain, would probably now be deemed rigid and abusively punitive by UK twenty-first-century standards. Neglect and emotional abuse often occur within settings which are chaotic, with weak boundaries or with rigid, inflexible, unresponsive ones. However, such settings can be easily penetrated by someone with unacceptably deviant attitudes and behaviour towards children, which can result in a particularly dangerous situation for all family members.

A difference between physical or sexual abuse and neglect or emotional abuse is that, theoretically, parents can completely avoid physically or sexually maltreating their children. In contrast, most parents will have to wrestle with whether they are being neglectful if, for example, they allow their children to stay home alone. Similarly, emotionally abusive behaviour can be an extreme form of necessary parental control. It is sometimes difficult to determine exactly when normal scolding becomes abusive denigration or when the imposition of a reasonable limit tips over into arbitrary control.

The next question requiring a response is: Can emotional abuse and neglect be justifiably linked into one book when they appear so distinct? Neglect raises the spectre of a physically unkempt, thin, frail child who is not given adequate food, warmth, clothing or hygiene. Emotional abuse, in contrast, produces the image of the physically cared for child, who is nevertheless humiliated, scapegoated, verbally abused and made to feel worthless.

However, what bridges the two forms of abuse is emotional neglect. A child cannot be physically neglected while being fully emotionally nurtured. In cases of dire poverty, children may be physically deprived but loving parents will try to provide when the opportunity arises whereas neglecting ones will make little attempt to provide care even when circumstances improve. When parents have the wherewithal to provide physical nurture but do not do so, there will inevitably be limited empathy and understanding of the child. Similarly, where there is emotional abuse, there will be emotional neglect. For example, constant denigration inevitably means giving insufficient praise and failing to value the child.

One key difference between neglect and emotional abuse is that neglect is nearly always the responsibility of carers. In instances of children neglected in foster homes, boarding schools, residential hospitals and children’s homes, the staff are acting in loco parentis. Emotional abuse, in contrast, can be perpetrated by non-carers. Bullying in school by fellow pupils often takes the form of emotional cruelty. Racism or the taunting of children with disabilities by neighbours are similarly examples of emotional abuse.

We do not deny the importance of non-carer emotional abuse, that is mistreatment at the hands of bullies, neighbours and larger society, but it is not the main focus of this book. Children abused by people who are not carers or family members can usually turn for support to the people who are parenting them. It is acknowledged that, in practice, this is not always the case. There have been tragic instances of children bullied by their peers beyond endurance who have not wanted to burden their parents with their worries and have subsequently committed suicide. Although we recognise the importance of helping young people who are abused outside the family, the attention of this book is on those children for whom their home is neither a source of love and nurture nor a place of sanctuary and comfort.

Cosmological model of children’s development

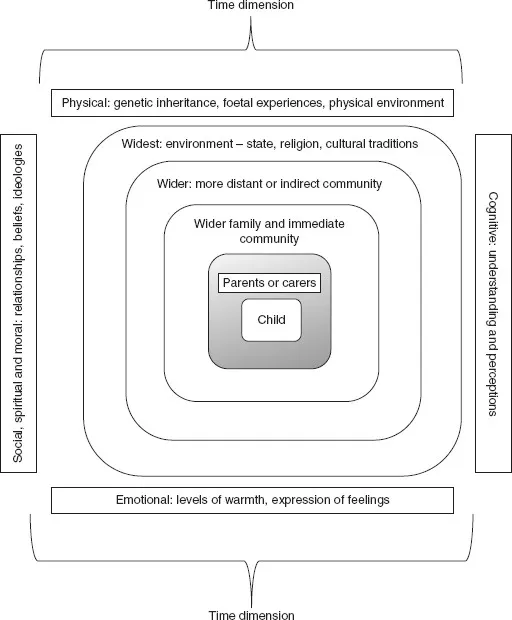

Underpinning the discourse in this book is our cosmological model of children’s development. This is adapted from Bronfenbrenner’s (1979) concept of an ecological model which positions the child in a series of nests which he terms ‘systems’. In the innermost nest is the ‘microsystem’ comprising the person with his or her physical features and roles and immediate relationships. Surrounding this is the ‘mesosystem’, which is the interplay of the person and their key settings, such as nursery, school or even a social services department. Encircling this is the ‘exosystem’, broader organisations touching the child less directly. Finally, there is the ‘macrosystem’, which refers to wider cultural influences and the overarching ideologies of a society.

We prefer to adopt the idea of cosmos. This is derived from the Greek term κóσμος (kosmos), meaning ‘order’. It proposes an ordered system as opposed to chaos. Wilber (1998) clarifies that the word does not just mean the physical universe; he adopts the word Kosmos to mean the entirety of being, ‘the patterned nature or process of all domains of existence’ (p. 64). Our model similarly can address the whole of a child’s world. A child can only survive and develop confidently if the surrounding systems are reasonably ordered. As will be seen in the next chapter, when inquiries into cases of extreme abuse are examined, order had usually broken down and chaos ensued or an overly rigid system masked emotional turmoil and instability.

We have conceptualised the environments surrounding the child not as circular nests but as rectangles because there are four different elements of the environment and aspects of the child’s development plus a fifth underpinning time dimension (see Figure 1.2). The rectangles have curved corners because one element of development merges into the next. Here we describe the five aspects, but not in order of importance, because each is equally important for a child’s development:

(a) Physical: first, this is the child’s physiological make-up and growth and the influence of genetic inheritance and foetal experiences. Next is the physical environment. Is it safe? Is it comfortable? Is there sufficient nutrition? Then there is the wider community and environment. Are there outdoor spaces for the children to play? Are the streets safe? Finally, there is the widest geography and physical environment. For example, children developing in Alaska are likely to have different life experiences compared to those brought up in hot, dry countries.

(b) Cognitive: for the child, this is the development of reasoning skills and cerebral acuity. More immediately in the environment, it is the education provided initially by family and carers and then through formal schooling. Finally, there is the value placed on education, skills and training by the local community and the state, and how learning and cognition is promoted in each particular cultural context.

(c) Emotional: both families and societies might value different types of emotional expression. Some families may be ‘demonstrative’, in which children are cuddled and told they are loved, whereas others are less so. The emotions engendered in the child and the reaction of both the immediate family and wider society will have an impact on the child’s development.

(d) Social, spiritual and moral: this dimension encompasses relationships with other people and ways of behaving towards them. This includes standards of morality. Families, whether religious or not, have beliefs about human rights and how to relate to the wider world. Some families may be deeply influenced by religious beliefs whereas in others there is an absence of any spirituality. Tedam (2013) highlights the importance of spirituality in, by way of example, the lives of British Ghanaians. Singh (2013, p. 31) points out that the uncomfortable relationship social work has with religion has ‘made it reluctant to embrace a more informed understanding of religious differences and their implications for practice’. Although religion may sometimes be absent, families, schools and wider society still provide guidance about how to relate to others.

(e) Time: this is the fifth dimension and is similar to Bronfenbrenner’s (1994) ‘chronosystem’, which he described as the passage of time. This does not mean just the ageing of a person, but encompasses the changing environment as people progress through the life-course. Two people born at slightly different times will be influenced by different chronosystems. The idea of a time-dimension reflects the work of Elder (1998), with echoes of the ‘life course theory’ in terms of individual’s differing experiences over time.

Defining neglect and emotional abuse 1: Concepts in the literature

Concepts of abuse are ‘socially constructed’. This means that although victims have always suffered from abuse, at different times and in different societies there may be more, or less, recognition of the suffering. A clear example is of physical abuse: whereas the flogging of children in schools was seen not only as acceptable, but as necessary in the UK less than a century ago, now it would be seen to be abusive. There are similar changing concepts of neglect and emotional abuse which makes finding solid, unchanging, uncontroversial definitions difficult.

Although definitions of physical neglect have not been unduly contentious, it is difficult to measure what is meant by adequate food, clothing, shelter and supervision. It is also sometimes difficult to distinguish carers who abusively chose not to provide adequate resources from those who cannot do so, maybe due to poverty. The Working Together document (Department of Children, Schools and Families [DCSF], 2010, p. 39) explains that neglect ‘is the persistent failure to meet a child’s basic physical and/or psychological needs, likely to result in the serious impairment of the child’s health or development’.

The above definition covers many children’s needs, including ‘Neglect may occur during pregnancy as a result of maternal substance abuse’ (p. 39). Poor nutrition in pregnancy may be associated with poverty but can occur because a mother choses to eat t...