![]()

PART I

BACKGROUND AND CONTEXT

![]()

ONE

COGNITIVE INTERVIEWING: ORIGIN, PURPOSE AND LIMITATIONS

DEBBIE COLLINS

1.1 Introduction

The aims of this chapter are to provide you with an overview of the cognitive interviewing method and to illustrate how it can be useful to you in the development of a survey questionnaire. Specifically we will:

• Summarise the theory behind the method

• Set out its origins

• Describe the method and the interviewing techniques it uses

• Examine its limitations.

Let’s start by considering the purpose of a survey and the factors that can affect the data it produces.

A “survey” is a systematic method for gathering information from (a sample of) entities for the purpose of constructing quantitative descriptors (statistics) of the attributes of the larger population of which the entities are members. (Groves et al., 2009, p.3)

We carry out surveys because we want to find out information about the population of interest, and we want that information to be statistical so that we can answer questions such as how many, how much, of what strength and size? We want this information because it is needed by policy-makers and decision-makers in government (national and local) and organisations such as health authorities, service providers and advocacy groups to inform decisions about issues that affect citizens, service users and so on. And we collect this information typically by asking people questions.

There are many factors that can influence the accuracy of the statistics collected by a survey. These include:

• Sample design and implementation – for example the completeness of the sampling frame and how well the responding sample covers the target population.

• Data collection – for example the mode of data collection, the characteristics of the interviewer, the environment in which the interview takes place or the questionnaire is completed, and the design of the questionnaire.

• Data processing – for example how the data are edited and coded.

These factors can introduce errors and biases to the data collected, which can impact on the accuracy of the statistics generated by the survey (see for example, Biemer and Lyberg, 2003; Groves et al., 2009; Oksenberg et al., 1991).

In this book we are concerned with errors that can arise during data collection when asking people questions. The survey method is underpinned by the premise that if we use standardised tools and standardised procedures in collecting our data, we will be able to observe real differences between participants. By ‘standardised tools’ we mean questionnaires that determine the exact form of the questions to be put to each participant. By ‘standardised procedures’ we mean training interviewers to only read the questions exactly as worded, to use neutral probes, and so on (Fowler and Mangione, 1990).

However, standardising the questions asked may not on its own ensure that we obtain valid, reliable, unbiased, sensitive data (Fowler, 1995). One obvious problem is that participants may not understand the questions being asked of them – or not in the way that the question-designer intended.

Given the challenges posed by the question design task, as designers we need feedback on how well we are succeeding. Ideally, feedback is required before the main survey is committed, so that attempts can be made to improve questions that do not seem to be performing as they should. Fortunately, methods exist for checking whether or not the questions can be answered, and whether the response task is being interpreted and carried out in the way intended before a questionnaire is finalised. One of those methods is cognitive interviewing.

1.2 Understanding the question and answer process

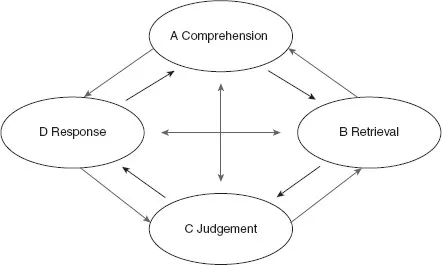

Cognitive psychology provides a useful model that can help us understand how participants answer survey questions. In its simplest form the model specifies four distinct processes that must be completed in order to answer a question. Participants must:

(a) comprehend the question;

(b) retrieve the necessary information (usually from long-term memory);

(c) make a judgement about the information needed to answer the question; and

(d) respond to the question. (Tourangeau, 1984)

In many real-life situations the question-and-answer process is probably not a simple linear progression but rather involves numerous iterations of and interactions between the different phases, as shown in Figure 1.1. For example, participants may make judgements at (C) about the level of detail needed to answer a survey question based on how difficult it is to retrieve the information required (B) and/or by the way in which answers are to be reported or the answer categories provided (D). This may then cause them to review (A). For example, is the question asking for the exact number of occasions I visited my doctor in the past six months, or is it asking for an indication of frequency – none, between 1 and 5, 6 or more? Having arrived at a provisional response at (D), I may then review it for social acceptability before actually reporting it. For example, will I appear out of the ordinary if I give the answer I am minded to give?

What has been said so far covers interviewer-administered questions. When the questionnaire is in a self-completion format, the question-and-answer process contains two additional stages: firstly participants have to perceive the information being presented to them (i.e. they have to recognise that this is a questionnaire that they need to complete); and secondly they have to comprehend the layout of the questionnaire: the visual aspect. Then they have to go through stages (a) to (d) above, and finally comprehend the routing to the next question. For further information on the cognitive steps involved in the question-and-answer process for self-completion questionnaires, see Jenkins and Dillman (1997).

Let us now look at each of the four main stages in the question-and-answer process in a little more detail.

1.2.1 Comprehension

There are a number of comprehension issues that you need to consider when designing and testing a survey question.

• Does the participant fully understand how the question is structured (syntax) and the vocabulary used?

• Is the participant able to keep all of this in mind when formulating an answer to the question?

• Does the participant understand the question in the way the researcher intended?

This last point is important because if participants interpret the questions in a different way from the way you intended as the question designer, conclusions drawn based on these answers may be flawed. Worse still, if different participants interpret the question in different ways from each other, and from what the researcher intended, comparisons between participants’ answers will not be valid. This is a problem because it can introduce systematic bias into survey estimates if certain types of participants interpret the question in particular ways.

Your goal is to design a question that can be understood by all participants, in the same way, and in a way the researcher intended. However, this is more difficult than it might first appear because the meaning of a question has two components – literal and intended. Literally understanding the words is not sufficient to be able to answer the question. Consider the following question and its use as an indicator of social inclusion

‘How strongly do you feel you belong to your immediate neighbourhood?’

The question’s intended meaning is to ask whether the participant feels part of his or her community. However, when participants interpret the phrase ‘belong to’ literally as being ‘the property of’, the question becomes difficult to answer. Focusing on the literal meaning is something that is seen among children and people whose first language is not that used by the questionnaire. A clearer wording of the question might be:

‘How strongly do you feel you are part of your immediate neighbourhood?’

How participants interpret such a concept within a question will depend on the context in which the question is asked, with participants drawing on the assumptions that are unthinkingly used in conducting daily conversation. This is because we often draw upon our stock of background information and knowledge in interpreting text, which means we will often fill in gaps, add details and make inferences based on our background stock of knowledge and what the survey interview requires (Grice, 1991).

1.2.2 Retrieval of information

Having comprehended the question the participant then (usually) has to retrieve the relevant information – be it factual or attitudinal – from long-term memory. This depends on the way in which the memory is stored or ‘encoded’ by an individual participant. In the case of factual information – either current or historical – a number of factors may affect the retrieval process.

Firstly, if the retrieval context is different to the original encoding context the participant may not be able to recognise that the event took place or be able to recall the correct event (Tulving and Thomson, 1973). Secondly, the rarer or more distinctive an event is, the more likely participants are to remember it. Consequently similar, commonly occurring types of event such as routine journeys or interactions will be harder to distinguish and recall individually (Anderson, 1983). Moreover, over time participants are likely to have experienced more similar events, so that rare or more distinctive events will become scarcer. This means that accurate recall (memory) of many events will become more difficult because there are fewer distinctive events, see Example 1.1 (Gillund and Shiffrin, 1984; Johnson, 1983).

Example 1.1 Remembering commonly occurring events

Remembering details about what I did on my first day at work in my current job diminishes the longer I am in my current job because I have more memories of work days featuring similar activities from which to select my first day.

Finally, often details are lost in the encoding process and inferences and interpretations are added. This can result in individuals ‘recalling’ in all sincerity events that did not actually occur. Such inferences may be added in response to the retrieval context, for example inferring the severity of damage sustained by a vehicle in a car accident from how the accident was described by the questioner rather than recalling the film footage of the accident (Loftus and Palmer, 1974).

In summary, there are several processes involved in the retrieval of factual information, including: adopting a retrieval strategy; generating specific retrieval cues to trigger recall; retrieving individual memories; and filling in partial memories through inference (for example, ‘what I must have done is…’). Certain characteristics of the question and the material retrieved from memory can affect the completeness of the retrieval phas...