![]()

PART I

THEORY AND PRACTICE OF COUNSELLING FOR ANXIETY

1

Introduction

Imagine a world without fear or anxiety. A new-born baby, entering such a world, would not survive long. Without innate fears, such as fear of strangers, the unknown, the unexpected, the dark, creeping insects, or heights, the curious child would soon be unprotected from danger, not knowing that the fear response leads them to safety. The fear response enables us to survive: being rightly fearful of actual dangers leads us all to take care, to seek help, to fight the dangers or run away. Bowlby (1969) described how animals of all species are genetically biased to respond with anxiety to any stimuli that are cues to potential danger to that species. Such threats include not only obvious threats to life, but also anything that endangers our relationships with other people. We are social beings: our need to relate and be close to other humans plays such an important role in the survival of humans as a species that it is not surprising that anxiety can be aroused by anything perceived as potentially disrupting or damaging to our interpersonal relationships, often a central theme in counselling.

The fear response can be overcome in extreme situations, such as bungee jumping, tightrope walking across two hot air balloons, getting friendly with tigers. The authors cannot speak with personal experience about overcoming such extreme dangers, but many of us are familiar with the experience of fear and anxiety, and have been both saved from danger and limited by our individual fears.

Anxiety is the experience of fear which has overtaken the sense of ‘objective’ danger. The line between, on the one hand, normal, sensible levels of fear, and anxiety on the other is a fine one. Most of us are familiar with the experience of anxiety: anxiety about failing exams, about being thought well of by friends, about travelling to new places and so on. We may feel anxious meeting a new client, giving a talk, writing a book. All these might seem entirely normal and understandable. For an infant to be nervous of strangers and start crying, is normal; for an adult to be so scared of other people’s evaluation that the individual is unable to speak to others without being overwhelmed by fear, is classified as anxiety. To be vigilant when crossing the road helps us to avoid stepping in front of traffic; to be so scared of something awful happening that the individual cannot leave the house, is anxiety. In these cases the fear response has spiralled out of control, bringing into play a host of other ways of being: we start behaving differently, avoiding things that make us anxious, trying to cope with the anxiety, or worrying excessively. We are beginning to enter the realm of anxiety disorders.

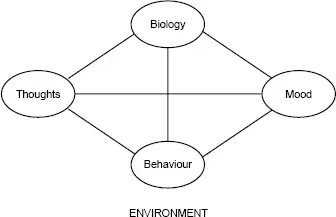

In this chapter we describe the experience of anxiety, and look at how it can be understood in terms of a network of different interacting elements: cognition, emotion, biology, behaviour and environment. We describe how these elements are dominant to different degrees in different problems: for example, the cognitive activity of worry predominates in generalised anxiety problems; panic attacks may be primarily a physical experience; agoraphobia is characterised by the behaviour of avoidance, such as not leaving the house. We describe the different forms of anxiety our clients may experience and present with, and suggest how diagnostic categories can be useful in helping both to understand our clients’ difficulties and to plan our counselling. We look at the evolutionary origins of anxiety, enabling us and our clients to gain a more sympathetic understanding of problems which result from over-effective evolutionary adaptation. We end by looking at how clients with anxiety problems present to counsellors.

Understanding Anxiety

Early psychotherapeutic formulations of anxiety centred on the psychodynamic concept of repression developed by Freud. This was founded on the idea that many anxieties took on the function of helping to repress much deeper worries, often associated with the sexual content of the unconscious. Although these ideas are no longer so influential, they contain several features which have proved of enduring value. Most modern concepts of anxiety, for example, give ‘avoidance’ a central place in the maintenance of anxiety problems and this involves a type of repression, yet not that of the strictly Freudian mode. Additionally, more recent approaches to anxiety have returned to the concept of trait anxiety, the view that certain people have enduring personality traits which make them more predisposed to developing anxiety disorders. Thus, as Freud proposed, there might be much deeper, personality-based aspects to anxiety than has sometimes been suggested by others who have focused on ‘state’ anxiety. The behaviourists have been particularly keen to challenge the psychodynamic view of anxiety. Watson and Rayner (1920) in their famous ‘Little Albert’ experiment, conditioned a little boy to be fearful of white rats, and wrote rather gloatingly that some psychoanalysts would later attribute the boy’s fears to a deep-seated anxiety in the unconscious. As will be seen later, while learning does undoubtedly play a role in the development of anxiety disorders, it is far from a complete explanation of the phenomenon.

In more recent models, anxiety is understood to arise when the individual has certain beliefs about the dangerousness of situations which hold important individual meaning for that person. Once situations, events, sensations and mental events are seen as dangerous, a complex web of emotions, actions, physiological reactions and thoughts is formed. This leads to the cycles of anxiety which cognitive therapy has aimed to describe, understand and change (Clark, 1999a). The central theme of anxiety problems, in contrast to other difficulties, is that anxiety is based on anticipating problems in the future: ‘I will die’; ‘I will lose my job’; ‘My partner will leave me’; ‘I will make a fool of myself.’ In this respect, it differs from depression, which tends to be more associated with the past – ‘I failed’; ‘I’ve been abandoned’ – and with hopeless rather than threatening predictions about the future: ‘There’s no point, nothing will change.’ While loss is the key cognitive theme of depression, for anxiety it is the theme of impending threat and danger (Beck et al., 1985).

Elements of Anxiety

Anxiety is a complex, multifaceted experience, a feeling which comes flooding into our whole selves, affecting many different aspects of our being. It was eloquently described by one of our clients as ‘a sudden visitor who has a habit of calling unexpectedly and penetrating into every nook and cranny of my house all at once – and who won’t take any hints to leave’. Anxiety is a combination of different elements – cognition, emotion, biology, behaviour and environment – which are linked and trigger one another off. A generic model for understanding anxiety is shown in Figure 1.1, and illustrated by the following short examples:

Figure 1.1 Generic cognitive models for understanding anxiety

Source: Padesky and Mooney (1990) (reproduced with permission)

© 1986 Centre for Cognitive Therapy

Anxiety affects us physically, with a large number of somatic symptoms:

An explosive tight feeling in my chest.

I worried to the point where I began to feel dizzy and sick.

My heart was racing and seemed to be missing beats.

Anxiety affects the way we think and use our mental powers:

I think to myself ‘I’m going trippy again . . . I’m going mad . . . You must think I’m a loony.’

I thought to myself ‘I can’t go to work like this, I’d screw up for sure.’

I thought that if I just keep trying to work this out, I’ll work out the answer but my attention kept wandering, I never did work it out.

Anxiety is itself an emotion and is strongly related to other emotions. Anxiety can result from other emotions, such as low mood or depression, and can produce many other emotions:

I felt really happy that Sue wanted to see me but then I began to really worry – perhaps she is just going to hurt me again.

I used to be really worried and work myself into huge anxiety states about my job but just lately I seem to have given up and I’ve been feeling so down.

Anxiety affects what we do and how we lead our lives: our behaviour:

I used to worry so much about my business presentations that I started turning up early so I could plan every single aspect of it. One time I got there before the office even opened and the cleaner called security, I was terrified that it would be reported and I’d be seen as an emotional wreck.

I felt so awful I knew I had to leave the restaurant– I mumbled something and rushed out to the loo, I was in there for ages and then asked my husband to get me home as soon as possible.

There are also enormous social and environmental factors in anxiety that both trigger and maintain problems, as Chris’s situation demonstrates. Chris was originally in a public sector job which had very little to do with selling services. During the 1990s, when introducing the business ethic to public services was seen as a way of making them more efficient, his job changed so that he had to sell the services of his agency.

You have to go out and sell the research services we have. I have never had to do things like that. I have had no training for it and, looking back, it wasn’t me at all. The other thing is that you kind of came to feel that being a public service person was a bad thing to be, like you were inefficient by definition almost – so this isn’t the best frame of mind to go out and sell yourself and the agency. . . . Now it is hinted that your job depends on generating income. There are constant reorganisations and threats of redundancy. There haven’t been any yet but several people have gone on early retirement or through ill health.

Anxiety is a complex network of all these elements, all of which are linked by cause and effect to each other. Thoughts, feelings, physiology, behaviour and environment interact with each other in many different ways, each playing varying roles in the different anxiety problems. The elements of anxiety and their interactions are described in more detail in Chapter 2.

Anxiety can be very disruptive, weaving its way into the individual’s personal relationships, social life and work. It may begin subtly – beginning to prepare slightly more than usual for giving lectures – but then roller-coasting towards spending hours preparing, lying awake at night worrying about whether the teaching is good enough, and eventually having to give up teaching, because of anxiety.

Types of Anxiety Problems

The thorny issue of diagnosis

Diagnosis is a medical task which creates a simple dichotomy between the sick and the well. (Pilgrim, 2000: 304)

One of the many fascinating aspects of anxiety is its wide and varied expression and the range of problems categorised as ‘anxiety disorders’. The panic-prone individual and the worrier may be easier to stereotype than the apparently accomplished socialite who engages in a multitude of hidden ‘safety’ behaviours to prevent other people’s negative evaluation, or the individual with obsessive compulsive disorder who internally tries to control his or her thoughts.

In this book, we divide anxiety problems into the different disorders as described by the diagnostic systems of DSM–IV and ICD 10 (International Classification of Diseases, 10th edn.). Since 1952, the American Psychiatric Association has published a Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) on a periodic basis, the latest being the revised edition in 2000 (DSM–IV-TR). The value and use of DSM criteria to understand, categorise or offer therapy to our clients is a rich source of reference and also a minefield, full of debate and lack of resolution, and is a controversial topic in the therapeutic world. We summarise some of the debate and present our rationale for using diagnostic categories in a parsimonious and thoughtful way to guide our counselling practice for anxiety.

Diagnostic categories are much used in psychotherapy research, particularly in cognitive therapy, where researchers attempt to define a uniform population in order to generalise results to other uniform populations. They are also used in psychiatry, where matching the right pharmacological therapy to the problem is vital. However, in the world of counselling and psychotherapy we are aware of the pitfalls. Strawbridge and James (2001) and Sequeira and van Scoyoc (2001) summarise a debate on the issue held by the British Psychological Society Division of Counselling Psychology, listing concerns such as the questionable nature of categories, the power of labelling clients, pathologising distress, the risk of using psychiatric and research categories outside these contexts, and competence of practitioners to diagnose, given limited training in using diagnostic tools.

For a number of reasons, we believe that using some system to classify and categorise the different forms of anxiety our clients are experiencing is important. We would take a pragmatic approach, and look for what may be helpful in using ‘labels’ and try not to get sucked into being absolute or obsessional. A pragmatic view of diagnostic categories is to see them as useful guidelines for practitioners to help us to understand and help our clients, but also as guidelines to be reviewed critically. We need to avoid reifying diagnostic categories, that is, treating them as more discrete and ‘real’ phenomena than they actually are. In particular, being clear about clients’ problems can help us to gear up our therapy to be more effective. Much of the work on cognitive therapy for anxiety has shown how specific approaches work well for specific anxiety problems, as described in later chapters. Methods of formulation and specific techniques to use have been shown to work differently with different problems: for example, some of the methods to identify and challenge thoughts that are useful for managing panic attacks may become counterproductive and unhelpful for problems such as general anxiety and worry. The importance of clarifying what the problem is in order to find solutions is illustrated in the case of Stan:

Stan was a young man who came for employee counselling for help with excessive anxiety and panic. Initial counselling focused on helping him to deal with his panic attacks. As counselling proceeded, it became clear that feelings of panic mainly happened when he had to meet a new client at work and in other unknown social situations. Stan imagined that other people, especially potential clients, were negatively judging him from the word go. It became clear that his problems lay mainly in the arena of social anxiety, which needed addressing directly in counselling. After realising this, it made more sense to help Stan learn to check the evidence more closely on whether people were judging him, rather than try to help him to stay calm in the face of supposed judgement.

Categories of anxiety problems

DSM–IV (APA, 2000) describes seven main ‘anxiety disorders’: panic, agoraphobia, specific phobia, social phobia or anxiety, obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD), post traumatic stress (PTSD) and generalised anxiety disorder (GAD). An eighth type of anxiety is health anxiety, classified as hypochondriasis in the somatoform disorders, despite sharing many of the salient characteristics of anxiety problems. Many have characteristics in common, but differ according to whether there are specific trig...