- 192 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Trafficking and Global Crime Control

About this book

In a world where global flows of people and commodities are on the increase, crimes related to illegal trafficking are creating new concerns for society. This, in turn, has brought about new and contentious forms of regulation, surveillance and control. There is a pressing need to consider both the problem itself, and the impact of international policy responses.

This authoritative work examines key issues and debates on human trafficking, drawing on theoretical, historical and comparative material to inform the discussion of major trends. Consolidating current work on human trade debates, the text brings together key criminological and sociological literature on migration studies, gender, globalization, human rights, security, victimology, policing and control to provide the most complete overview available on the subject.

Suitable for students, academics and scholars in criminology, criminal justice, sociology and international relations, this book sheds unique light on this highly topical and complex subject.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Trafficking and Global Crime Control by Maggy Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Contested Definitions of

Human Trafficking

Introduction

There is now a plethora of state bodies, non-governmental organisations, specialised networks of counter-trafficking agencies, United Nations and other international organisations that have produced a number of multi-lateral agreements, international and regional conventions and declarations against trafficking,1 research reports, conference papers, action plans, good practice guidelines and technical assistance toolkits. For example, the United Nations launched a Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking in 2007 to promote ‘a global, multi-stakeholder strategy’ to tackle ‘a crime that shames us all’; the initiative boasted a range of collaborative partners from government and non-governmental organisations, transnational corporations, to celebrity-led networks of goodwill ambassadors.2 Much of this information-work and scholarly research on trafficking is underpinned by the assumption that human trafficking is a phenomenon whose ‘truth’ can be uncovered – who are the traffickers and victims? How big is the problem? Exactly what type of exploitation is involved?

In practice, the answers to such questions are far from straightforward. Human trafficking is an imprecise and highly contested term (Salt and Hogarth, 2000).3 There are multiple, sometimes oppositional, and shifting understandings of trafficking. As different ‘claims makers’ (Cohen, 1995) construct raw events into information, make empirical and moral claims, some forms of exploitation may become more obscure, be deemed less politically significant, or less morally offensive than others in the trafficking debate. Definitional struggles about human trafficking tend to be dominated by state officials and other powerful groups, generally with very little input from trafficked victims themselves. Further, the proliferation of information-work on human trafficking has been shaped by global media and information flows: witness, for example, the high-profile UN Global Initiative to Fight Human Trafficking and its use of the global media in an increasingly message-dense public arena.4 So what are the different ways of framing and talking about the nature, causes and consequences of human trafficking? In what ways are they influenced by wider assumptions and processes? And how have these conceptualisations of the problem shaped the contemporary responses to trafficking?

Creating a knowledge-base for human trafficking

Much of the existing knowledge-base for the global problem of human trafficking is premised on the estimated volume of trafficking, apprehension records, government organisation or NGO case records, research case studies on known cases of trafficking and trafficked victims. The International Organisation for Migration (IOM), for example, has developed a Counter-Trafficking Module Database, ‘the largest global database’, which includes information on almost 7,000 known trafficking victims from 50 source countries and 78 destination countries (www.iom.int). Yet, data produced by state bodies, non-governmental or religious organisations, international agencies and independent researchers on trafficking are beset with ambiguities and limitations.

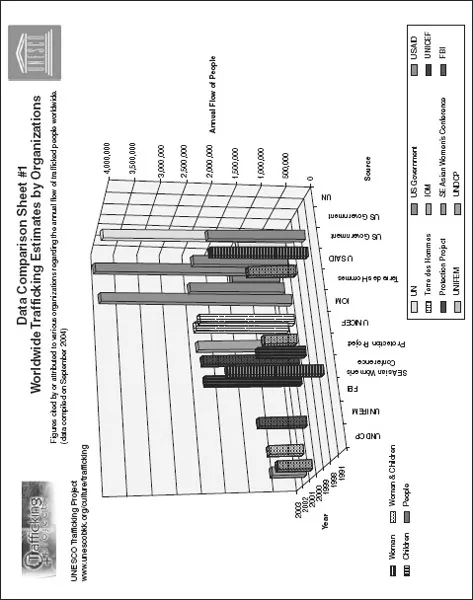

Despite continuous media reports and mainstream policy statements that human trafficking is widespread and on the rise, there remains an absence of reliable statistical data. As Sanghera (2005) noted, there is no sound methodology to estimate the number of people trafficked, and the merit of existing estimates and reported figures remain disputed. There has been a wide range of estimates of the size of the human trafficking problem by organisations worldwide. This is illustrated here in a datasheet compiled by the UNESCO Trafficking Project (Figure 1.1).

As UNESCO noted in the introduction to its Trafficking Project, divergent and often contradictory trafficking estimates may ‘take on a life of their own, gaining acceptance through repetition, often with little inquiry into their derivations’ (www.unescobkk.org). One of the most oft-quoted figures of trafficking came from the US Government. Based on CIA-derived estimates, the State Department’s Trafficking in Persons (TIP) report estimated that ‘700,000 to 2 million women and children are trafficked globally each year’ in 2002 but inexplicably revised the figures to ‘600,000 to 800,000 victims of all types of trafficking’ in 2005. Domestic numbers of trafficked victims are also highly fluctuating: in 2002, the State Department’s TIP report claimed that 45,000–50,000 persons are trafficked into the USA annually, but the number was revised to 18,000–20,000 a year later; in 2004, the report cut the figure to 14,500–17,500 per year. These figures have generated much critique and scepticism. The US Government Accountability Office, for example, has expressed concerns that the accuracy of the trafficking figures provided by the US Government and other international organisations is ‘questionable’ because of weak and unclear methodologies; limited reliability, availability and comparability of country-level data; and a discrepancy between the numbers of observed and estimated victims of human trafficking (US Government Accountability Office, 2006).

Figure 1.1 UNESCO Trafficking Statistics Project datasheet

Source: http://www.unescobkk.org/fileadmin/user_upload/culture/

Trafficking/project/Graph_Worldwide_Sept_2004.pdf.

Trafficking/project/Graph_Worldwide_Sept_2004.pdf.

Criminologists have long noted the socially constructed and skewed nature of official crime statistics; official statistics are the product of police work and crime control priorities and suffer from the problem of the ‘hidden figure of crime’. In addition, there are particular problems associated with collecting and interpreting various types of trafficking data (Salt, 2000; Lee, J., 2005; Di Nicola, 2007). Trafficking estimates tend to suffer from a lack of standard definition of trafficking offence and victim. Many countries lack specific counter-trafficking legislation, clear structures for victim identification and referral, or their laws may only define human trafficking in particular contexts (e.g., sex trafficking, cross-border trafficking) and not others (e.g., trafficking for labour exploitation, internal trafficking).

The general lack of methodological transparency has meant that the empirical basis of figures on official apprehensions, victim identification and the dismantling of supposed smuggling and trafficking networks is not verifiable. Data related to different forms of unauthorised migration may be lumped together to produce an aggregate figure, as border control authorities do not always distinguish between trafficking, smuggling and irregular migration. Trafficking victims may be misidentified by law enforcement agencies as illegal migrants, who are deported immediately without referral to assistance agencies or shelter homes. Alternatively, their numbers may be grossly inflated when large proportions of migrant sex workers or those caught up in police raids are assumed to be ‘sex slaves’ controlled by traffickers and pimps.5 The identification of traffickers is also far from straightforward. Criminal cases relating to suspected traffickers may not be registered or else registered as ‘procuring’ or ‘living off the avails of prostitution’.

Our existing knowledge-base for human trafficking is heavily shaped by institutional exigencies and research access. As Laczko and Gramegna (2003) pointed out, research data are often based on the various trafficking definitions used by each individual agency and only cover known cases who have received certain types of assistance (e.g., persons participating in voluntary assisted return programmes or those accommodated in shelters for trafficked victims). The result is a vicious circle: less is known about human trafficking in particular regions or for particular purposes such as forced labour and servile marriages; their problem remains under-reported or redefined as something else, thereby making our knowledge and understanding of trafficking partial and skewed. In this regard, Kelly (2005a: 237) suggests that ‘a wider framing might change what we think we know about the prevalence and patterns involved [in trafficking]’. Finally, enforcement agencies may be tempted to manipulate trafficking figures to boost their efforts in combating illegal immigration, to argue for more resources, or to obscure failures. Similarly, researchers and NGOs may make unsubstantiated or biased claims about the scale of trafficking or the ‘truth’ about victims’ experiences, especially when researchers hold entrenched views about sex trafficking or when a significant amount of institutional funding is at stake.

What is human trafficking?

There are six key conceptual approaches commonly used to make sense of human trafficking: (1) as a modern form of slavery; (2) as an exemplar of the globalisation of crime; (3) as a problem of transnational organised crime; (4) as synonymous with prostitution; (5) as a migration problem; and (6) as a human rights challenge. These approaches may coexist, overlap and change over time, or they may contradict each other. Significantly, interventions are inseparable from conceptualisations of the problem. Trafficking will be approached differently depending on whether it is considered a problem of illegal migration, prostitution, or organised crime. Different interventions will be developed, and trafficked persons will be dealt with differently, depending on whether they are considered illegal migrants, prostitutes, victims of trickery or of ignorance, or the abused bearers of human rights.

Slavery

First, human trafficking has been conceptualised as a modern form of ‘slavery’ (Miers, 2003; Ould, 2004; Bales, 2005; Smith, 2007). When the UK commemorated the bicentenary of the 1807 Abolition of the Slave Trade Act, human trafficking was held up as one of the ‘many guises [of slavery] around the world’ (Blair, 2006). While old forms of slavery condoned and regulated by states – with kidnapping, auction blocks and chattel slaves forced to work in chains – may be rare today, scholars have argued that modern practices of human trafficking contain an element of extreme and direct physical or psychological coercion that gives a person control over another’s life akin to slavery.

According to Kevin Bales, new slavery refers to ‘the complete control of a person for economic exploitation by violence or the threat of violence’ (2000: 462). To Bales, new slavery is not marked by legal ownership of one human being by another or permanent enslavement; instead, it is marked by temporary ownership, low purchase cost, high profits, debt bondage and forced labour (Bales, 2000; 2005). In short, new slavery is part of an illicit, unregulated economic realm in which people are treated as ‘completely disposable tools for making money’ (Bales, 1999: 4).

A number of institutions and conventions associated with the United Nations and regional bodies (e.g., the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe, the Council of Europe, the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation) regard trafficking and slavery as fundamentally linked human rights violations because both involve the severe exploitation of an individual. The UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights explicitly stated that the term ‘slavery’ encompassed the ‘traffic in persons’ (OHCHR, 1991). The International Criminal Court’s Rome Statute instructs that enslavement involves ‘the exercise of any or all of the powers attaching to the right of ownership over a person’, including ‘the exercise of such power in the course of trafficking in persons, in particular women and children’.6

Scholars who insist on the value of using the term ‘slavery’ argue that it alerts us to the ‘underlying and essential elements’ of ‘manifested violence and its threat, absolute control, economic exploitation’ (Bales, 2000) and that it ‘guarantees a wider audience’ in the fight against present injustice (Anker, 2004). Indeed, governments and NGOs alike have often made use of powerful images and testimonies of women and girls who are enslaved and subjected to rape, beatings and torture in their information and awareness campaigns. Others, however, remind us of the need to avoid the sensationalism surrounding images of ‘sex slaves’ and are critical of the moralising agenda which is reminiscent of the ‘white slave panic’ at the end of the nineteenth century (see below) (Doezema, 2000; Anderson, 2004; O’Connell Davidson, 2006). Finally, legal commentators on decisions in the European Court of Human Rights and the International Criminal Tribunal for the Former Yugoslavia have noted the complexity and substantial variability in trafficking scenarios and warned against making a blanket claim on slavery: ‘whether a particular phenomenon constituted a form of enslavement would depend on a range of factors, including the level of control displayed, the measures taken to prevent escape, the use of force or coercion, any evidence of abuse, and so on’ (Munro, 2008: 248).

Globalisation

Second, human trafficking has been seen as an exemplar of the globalisation of crime. Much has been written about the criminogenic effects of globalisation. The social, cultural and technological conditions of globalisation (in particular, increases in the extent of global networks, the intensity of worldwide interconnectedness, the velocity of global flows of people and ideas) have arguably created ‘new and favourable contexts for crime’ (Findlay, 2008). One strand of the globalisation of crime thesis is encapsulated by what Passas (2000) has termed ‘global anomie’, which is most apparent in the socio- economic milieu in Russia and many of the former Eastern bloc societies. To Passas, globalisation and its associated de-regulation of capital, trade and business under neo-liberalism have produced systemic strains and asymmetries:

As needs and normative models are ‘harmonized’, people become conscious of economic and power asymmetries, and directly experience their impact. Globalization and neoliberalism heightened this awareness, further widened the asymmetries … In the end, most people realize that the attainment of their lofty goals and lifestyles is beyond reach, if they are to use legitimate means. The success in spreading neoliberalism has brought about a series of failures: more poverty, bigger economic asymmetries, ecosystem deterioration, slower and unsustainable growth patterns. At the time that societies most needed the shield of the state to cushion these effects, welfare programs, safety nets, and other assistance to the poor … forcibly declined or disappeared. Thus, global neoliberalism systematically causes relative deprivation as well as absolute immiseration of masses of people. (ibid.: 24)

A second strand of the globalisation of crime thesis focuses on the increased opportunities for crime and operational capabilities of organised crime groups especially through developing ‘a nearly indecipherable web of nodes and illicit relations’ in criminal activities (Shelley et al., 2003). Traditional organised criminal actors and groups have arguably adapted to the pressures and opportunities of globalisation to generate new illicit flows of people, money and goods (including sex trafficking, money laundering, trade in toxic waste and endangered species):

[W]ith increasing globalization, national criminal gangs are now operating outside their traditional jurisdictions. Not only do mafia groups work in association with other criminal organisations, but they also set up their own operations in other countries. For example, the Russian mafia traffics women from Germany … Another case of nationals working in foreign lands is the recent [Chinese] Triad activity in Canada … The instances of organised crime’s operation and collusive activities are numerous and varied. (Shannon, 1999: 129)

Manuel Castells (1998) applied the imagery of transnational networks to the field of organised crime, whereby criminal organisations are said to be able to link up with each other, setting up their operations transnationally, taking advantage of economic globalisation and new communication and transportation technologies. The global criminal economy of trafficking (of drugs, arms, and people, including organs) has arguably expanded its realm to ‘an extraordinary diversity of operations’, making it an ‘increasingly diversified, and interconnected, global industry’. Although such views have been influential among policy-makers, critics of Castells’ approach and the associated discourse about transnational organised crime are sceptical of the overstated influence of omnipotent criminal syndicates, their supposed structural logic of organisation, and their unified purpose (Friman and Andreas, 1999; van Schendel and Abraham, 2005).

Transnational organised crime

Third, human trafficking has been concept...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgements

- Acronyms

- Introduction

- 1 Contested Definitions of Human Trafficking

- 2 Contemporary Patterns of Human Trafficking

- 3 Constructing and Denying Victimhood in Trafficking

- 4 Trafficking and Transnational Organised Crime

- 5 The War on Human Trafficking

- 6 Transnational Policing in Human Trafficking

- 7 Rethinking Human Trafficking

- Appendix A: Timeline: Key international conventions and national legislation against human trafficking

- Appendix B: Useful Websites

- Bibliography

- Index