- 200 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Have the music and movie industries lost the battle to criminalize downloading?

This penetrating and informative book provides readers with the perfect systematic critical guide to the file-sharing phenomenon. Combining inter-disciplinary resources from sociology, history, media and communication studies and cultural studies, David unpacks the economics, psychology and philosophy of file-sharing.

The book carefully situates the reader in a field of relevant approaches including network society theory, post-structuralism and ethnographic research. It uses this to launch into a fascinating enquiry into:

This penetrating and informative book provides readers with the perfect systematic critical guide to the file-sharing phenomenon. Combining inter-disciplinary resources from sociology, history, media and communication studies and cultural studies, David unpacks the economics, psychology and philosophy of file-sharing.

The book carefully situates the reader in a field of relevant approaches including network society theory, post-structuralism and ethnographic research. It uses this to launch into a fascinating enquiry into:

- the rise of file-sharing

- the challenge to intellectual property law posed by new technologies of communication

- the social psychology of cyber crime

- the response of the mass media and multi-national corporations.

Matthew David concludes with a balanced, eye-opening assessment of alternative cultural modes of participation and their relationship to cultural capitalism.

This is a landmark work in the sociology of popular culture and cultural criminology. It fuses a deep knowledge of the music industry and the new technologies of mass communication with a powerful perspective on how multinational corporations seek to monopolize markets, how international and state agencies defend property, while a global multitude undermine and/or reinvent both.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Peer to Peer and the Music Industry by Matthew David in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Criminology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Introduction

- Much too much?

- The file-sharing phenomenon

- The structure of this book

- The claim being made

Much too much?

Two wars rage today: one to control scarce ‘pre-industrial’ fossil fuels; the other to control non-scarce ‘post-industrial’ informational goods. Global capitalism requires the fusion of energy and information. Managing scarcity in that which is naturally scarce and in making scarce that which is not becomes paramount. ‘Corporate power is threatened by scarcity on the one hand and the potential loss of scarcity on the other’ (David and Kirkhope 2006: 80). That every networked computer can share all the digital information in the world challenges one of these domains of control. In such conditions, sharing has been legislated against with a new intensity.

Scientists ‘manage the horror’ (Woolgar 1988) of never being truly sure, with secondary repertoires, circular devices that give a sense of security and closure that is otherwise lacking when confronting a confusing world. This book looks at how parties to disputes over file-sharing ‘manage the horror’ of having no legal, technical, social or cultural foundations by which to secure their economic interests, identities, strategies and alliances in relation to the production and circulation of informational goods.

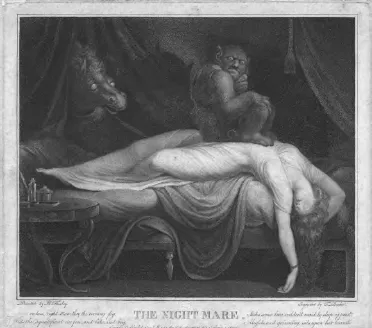

Nonetheless, one person’s horror is another person’s blessing. Henry Fuseli’s 1781 painting, The Nightmare (see Figure 1.1), was pirated within months of its first authorised reproduction (David 2006b). Fuseli was as upset by the limited payment he received for the authorised reproductions as he was with the pirates, who were distributing his name across the whole of Europe with cut-price editions that made him a household name and his work an affordable household item. Such fame added to the value of the authorized versions. To bypasss contracts already signed, Fuseli simply painted new versions of his original and sold the rights to these. Finally he set up his own printing company. Additional contracts are prohibited today in contracts issued by major record labels. However, the value of free publicity and bypassing bottlenecks through self-distribution are still live issues. Fuseli’s business model might be a nightmare for today’s major labels, but such attempts to ‘manage the horror’ may benefit audiences and artists alike.

Figure 1.1 The Nightmare, Henry Fuseli, 1781 The Glynn Vivian Art Gallery, Swansea

The file-sharing phenomenon

This book is about file-sharing, the circulation of compressed digital computer files over the Internet using an array of location and exchange software. In making their music collections available online, file-sharers create a community of sharing that takes the affordances of network technology in a radical new direction. Hundreds of millions of networked computer users and upwards of a billion files made available at any one time challenge the monopoly power of major record labels, whose ongoing concentration stands in stark contrast to a free flow of information that threatens to sweep them aside.

File-sharing software has increasingly migrated from central server mediated forms of exchange to distributed forms of interaction. Each computer in the network acts as client and server. Distributed systems are a response to the criminalization of file-sharing software providers, uploaders, downloaders and even Internet Service Providers (ISPs). Legal moves come from film and music companies who object to material they seek to sell being shared globally. Legal strategies link to wider technical and cultural campaigns to control intellectual property in patent as well as copyright. Currently, dominant players in film and recorded music see file-sharing as a fundamental threat. They may be correct. They may or may not be successful. In the course of conflicts, the very fabric of ‘they’ shifts, as such file-sharing goes to the heart of contemporary network society, to informational capitalism’s discontents, challengers and those that seek to reinvent it.

The economic significance of informational goods increases in network societies (Castells 1996). So the potential to circulate such goods freely through the Internet raises the prospect, as spectre or salvation, of an end to scarcity – at least in the informational realm. Post-scarcity threatens profitability in goods that command a price only as long as demand exceeds supply. Businesses built on scarcity campaign hard to criminalize sharing. Protecting monopoly rights in informational goods, even in suspending market forces at one level, is deemed essential to the maintenance of market exchange relations in general. Suspending market entry is designed to maintain scarcity and hence prices.

Most technologies that undermine scarcity were themselves developed initially by the very companies now threatened. Today’s informational capitalist enterprises may be replaced from below or by higher forms of informational capitalism. File-sharing is not simply a product of informational capitalism; it may drive out the old only to make way for a newer, more powerful informational capitalism. Global media corporations are happy to profit from free content where they can. But alternatives also emerge. Castells (1996) suggests that the ‘informational mode of development’ (forces of production) are not reducible to the ‘informational mode of production’ (network capitalism), even as critics like Chris May (2002) suggest the two are not so distinct. Telecommunications and information businesses developed the digital recording and storage, along with compression and transfer protocols, that now assist challenges to their monopolies. Hackers extended initial products in new directions. The informational mode of development is not merely extending the dominant mode of production, it is threatening the fetters set in place by property rights regimes.

The structure of this book

The relationship between technical, economic and social networks and the dynamics of change are explored in Chapter 2. Neo-Marxists such as Castells, May and Kirkpatrick are contrasted with the more ethnographic work of Hine, Mason et al. and Miller and Slater, as well as the post-structuralism of Deleuze, Galloway and Kittler.

Chapter 3 explores the history of file-sharing; its first incarnation, Napster, the legal actions which led to its closure in 2001/2, the subsequent generations of software, and the laws that emerged to engage them and which in turn shaped subsequent technical modifications. While Napster’s central server offered a technical Achilles heel that allowed legal action against its providers, new generations of file-sharing software adopted ever more complete forms of distributed communication for location and exchange. This circumvented certain legal liabilities on the part of the software providers. The very limits to control have led to the growth of a mass audience for online digital material, and in a standard format that overcame the desire of individual suppliers to control their musical and film content. This created the conditions for a market in download services and MP3/4 players. Suspension of property rights in one domain created the possibility of new markets. Another development, alongside file-sharing, has been the parallel growth (from the same month in 1999) of social networking services. Chapter 3 ends by highlighting the parallel developments of audience file-sharing and the actions of artists reaching audiences by similar means, a theme explored further in Chapters 8 and 9.

A contradiction exists between the location of ideas within an irreducible web of cultural production and the notion of property as discrete units for private ownership. All formulations of intellectual property have recognized that allocation of ownership rights in ideas should only ever be partial and time limited, balancing the private interests of innovators with the general interest of the culture out of which all innovations arise. At a time when informational goods are becoming increasingly economically significant, laws to shore up ownership in ideas seek to sweep aside such balance. Chapter 4 demonstrates that perpetual and strong constructions of intellectual property rights have no assured basis in natural rights philosophy, romantic constructions of creativity or in utilitarian doctrines of the balance of interests. Today’s beneficiaries make universal claims to defend partial interests. States, individuals, industries and genres that achieve ‘success’ claim those coming after should defer to their ownership rights over past achievements. However, those states, individuals, industries and genres now seeking to protect intellectual property rights from younger actors themselves rose to success by disregarding the monopoly rights claimed by those that were dominant before them. Just as the old claim rights over the past, so the young (states, individuals, industries and genres) defend their exploitation of the creative commons on the basis of rights to development and over the future.

Chapter 5 picks up Chapter 3’s history of file-sharing, through the prism of legal developments outlined in Chapter 4. After Napster’s closure, distributed peer-to-peer softwares emerged and were themselves the target for legal attack. US court decisions in 2003 and 2004 upheld the 1984 ‘Sony Ruling’ which established the principle of ‘dual use’ whereby a provider of a product with legal applications cannot be held liable for unlawful applications if they are not directly party to such uses and have not actively promoted such uses. The result of the 2003 and 2004 rulings, despite a challenge to the Sony Ruling in 2005, shifted attention from software suppliers to file-sharers. This campaign is ongoing in a set of cross-cutting legal, technical and cultural forms which are explored in Chapters 6 and 7. Chapter 5 examines how legal developments have unfolded across the world. A global intellectual property framework through the World Trade Organization (hereafter WTO), the Agreement on Trade Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (hereafter TRIPS) and the World Intellectual Property Organization (hereafter WIPO) is emerging. However, the growth of ‘immaterial imperialism’ – global intellectual property rights regime – remains limited by diversity in national and regional interpretation and enforcement. The same legal text can be acted on, or not, or differently. Balance between intellectual property rights and human rights (to privacy and freedom of expression) provides scope for multiple challenges, modifications, exemptions and limitations to a universal and strong form of property rights in ideas, in principle and in enforcement.

Tension between encryption and surveillance in network communication extends long-standing modern concerns over anonymity and regulation. Chapter 6 examines digital rights management, in encryption and surveillance, as a technical mythology – both false and self-contradictory. If ‘strong’ encryption existed it would be as useful to copyright infringing file-sharers as such systems would be to copyright holders. Strong encryption runs up against the fact that all currently available music in the world is available in non-encrypted format, as CDs are not currently encrypted. Even if every new piece of music were encrypted, it would only take someone to hold a microphone next to a speaker to make a recording of it. But such a digital lock does not exist. Pure technical security is a myth. As long as someone is given the key, it remains likely that it will be leaked. Every encryption system ever developed to protect informational goods has been broken by the global hacking community. The hacker ethic, ‘the spirit of informationalism’ and/or ‘the informational mode of development’ itself, routinely upsets the existing mode of production and its regime of intellectual property rights.

Surveillance is used by recording industry proxies to trawl file-sharing networks for copyright infringement. However, similar techniques are used by file-sharers, through add-on software that blocks access to computers whose searching trawls rather than shares. As two sides of the same coin, encryption and surveillance do not in themselves determine outcomes. Rather, it is their use and the success or otherwise of the social networks of such applications that determine outcomes. Whether the resources deployed by hundreds of millions of file-sharers and hackers will prevail relative to the resources deployed by ‘content industries’ becomes the focus of attention. Such disputes take place at the level of courtrooms and legislatures, research and development laboratories and the global networks of hackers and open source programmers, mass-media storytelling and chat room/blogs, lobby group campaigning and content industry boardrooms, and in the dynamics of musicians and artists deciding how best to reach an audience, make a life and make a living, as well as in the everyday interactions of countless millions of people online. If file-sharing software shows how new technologies create new affordances that cannot be reduced to the existing balance of social relationships, encryption and surveillance software tend to highlight the counterpoint, which is that such affordances are not themselves able to suspend existing power relations. File-sharing is an asymmetric technology. Surveillance technology and encryption technology are both, individually and together, symmetrical ones.

The tension between exposure and closure is irresolvable. The desire to widen the circulation of information, whether as a profit-oriented content industry or as a ‘strength in numbers’ file-sharing community (the bigger the group the more there is for everyone to share – as copying is non-rivalrous), stands at odds with the counter desire to limit access in either the protection of scarcity and hence prices, or in protecting identity in an attempt to avoid prosecution. All sides to disputes seek to ‘manage the horror’ of their inescapable vulnerability with myths of power and security, whether by technical or other means. When courtrooms and gadgets so often fail – even as persuasive fiction – it is no surprise that much effort has been directed at mass-media representation, in the attempt to persuade non-experts that they should not, cannot, better not try to file-share. Chapter 7 addresses these attempts to manage the mass media. Linking file-sharing with commercial counterfeiting, bootlegging and piracy – and then linking all these with terrorism, drugs, drug dealing, illegal immigrants, school and university student plagiarism, and identity theft – seeks to engender both a moral rejection of copyright infringing file-sharing and the belief that both the chance and the cost of getting caught are very high. These claims are tenuous at best and have proven highly counterproductive, being largely rejected, disbelieved and inverted by those targeted. In a classic case of deviance amplification, lumping file-sharers, counterfeiters and pirates together under the label of ‘pirates’ has led many who are not, legally speaking, pirates to embrace their new-found deviant identity. The label ‘pirate’ has become a badge of pride. Claims concerning new clampdowns and initiatives do more harm than good. Exaggerated and inaccurate accounts discredit their proponents.

Yet mass-media coverage is more than just failed propaganda. Study of such news coverage reveals the relative weakness of bodies such as the British Phonographic Industry (hereafter BPI), the Recording Industry Association of America (hereafter RIAA), the Motion Picture Association of America (MPAA) and the Federation Against Copyright Theft (FACT) in controlling and framing the stories they push. Frames have not tended to endorse the content providers’ construction of reality. Media framing conflicts occur between organizations and institutions, and the voices of file-sharers never frame coverage, yet content industries face a range of other corporate bodies keen to contest their version of events. Large multimedia conglomerates, all of whom profit from the circulation of free content in one form or another, seem keen to carve up the empires of former dominant players. Record and film companies are often subsidiaries of the larger conglomerates that, in backing all the horses, appear willing to sacrifice some of their stable in the interest of winning on other bets. Many such companies have stakes in Internet service provision, mobile telephone networks, television, social networking sites, record companies, computer manufacture, software and gaming, as well as in film. The death of the major record label may see the rise of new grass-roots production and performance models of culture and business. It could be a stepping stone to a new age of ever more concentrated multinational and cross sector integrated corporate power. These alternative scenarios are explored in Chapters 8 and ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- List of Figures and Tables

- Key Acronyms and Abbreviations

- 1 Introduction

- 2 The Global Network Society: Territorialisation and Deterritorialisation

- 3 File-Sharing: A Brief History

- 4 Markets and Monopolies in Informational Goods: Intellectual Property Rights and Protectionism

- 5 Legal Genealogies

- 6 Technical Mythologies and Security Risks

- 7 Media Management

- 8 Creativity as Performance: The Myth of Creative Capital

- 9 Alternative Cultural Models of Participation, Communication and Reward?

- 10 Conclusions

- References

- Index