![]()

1 Technological Innovation

Variety in the Meaning Attributed to Invention, Innovation and Technology and the Organisation of this Book

This chapter begins with a review of definitions of technology and innovation. This is then used to develop the device of the ‘technology complex’, a device that is exploited in the organisation of the rest of this book. This preference for the logical development of an argument from first principles does mean that discussion of the organisation of the book is postponed to half-way through the chapter. The second half of this chapter demonstrates the value of the technology complex as an intellectual tool by arguing for the comparative inadequacy of the more readily available concepts applicable to innovation and technological change.

Invention, Innovation and Technology

There appear to be almost as many variant meanings for the terms ‘invention’, ‘innovation’ and ‘technology’ as there are authors. Many use the terms ‘invention’ and ‘innovation’ interchangeably or with varying degrees of precision. At an extreme, Wiener prefers ‘invention’ to describe the whole process of bringing a novelty to the market (Wiener 1993). In contrast, Freeman prefers to restrict the meaning and increase the precision of ‘innovation’ by only applying it to the first commercial transaction involving a novel device (Freeman 1982: 7).

Some definitions are in order. In this book ‘invention’ will be restricted to describe the generation of the idea of an innovation. Innovation will describe some useful changes in technology, and technology refers to the organisation of people and artefacts for some goal. In this book then, technology is both the focus of analysis and yet is given a very broad and inclusive meaning. This usage is in contrast to many other authors and so deserves further explanation.

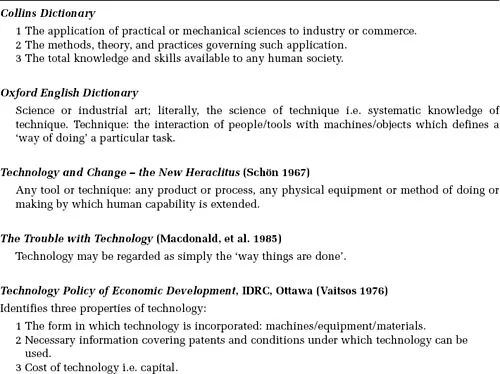

The term ‘technology’ is in a class of its own for variation in meaning and Figure 1.1 represents an effort to display some of this variety.

The ‘spread’ of definitions in Figure 1.1 has the striking quality that distinctly different elements appear in many of the definitions. The titles of the works from which the definitions are drawn show that the detail of the definition is linked to the discipline, or problem of study: industrial relations, organisational behaviour, operations management, and the problem of technology transfer. These are not ‘wrong’ definitions if one accepts the restricted focus of a subject discipline, problem or time frame and a general definition of technology should be able to incorporate such subdefinitions as special cases.

Figure 1.1 A range of definitions of ‘technology’ (from Fleck and Howells 2001: 524, reproduced with permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd)

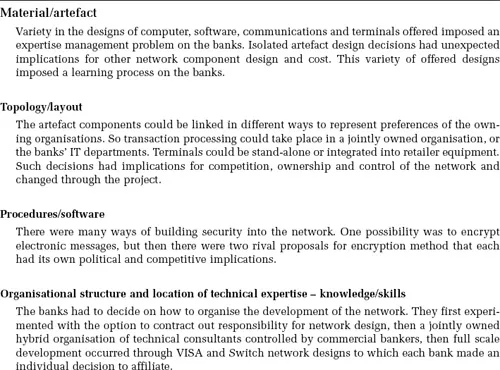

Examination of the range of definitions in Figure 1.1 suggests that a suitable general and inclusive definition of technology becomes the ‘knowledge of how to organise people and tools to achieve specific ends’. This is certainly general, but hardly useful, because the different elements of the subdefinitions have been lost. The technology complex1 in Figure 1.2 has been suggested as a device that relates the general definition of technology to its subdefinitions (Fleck and Howells 2001).

The elements within the technology complex have been ordered to range from the physical and artefactual to the social and the cultural.2 This captures the idea that there are multiple ‘levels’ within society at which people organise around artefacts to create working technologies. Any or all of these elements could be analysed in a working technology – a technology ‘in use’. It is rather rare that a full range of elements are considered, but it will prove worthwhile to provide some examples of when it makes sense to extend the range of analysis over the range of the technology complex.

Figure 1.2 The technology complex (from Fleck and Howells 2001: 525, reproduced with permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd)

Use of the Technology Complex3

An example of how an apparently simple technology nevertheless includes a range of these elements is given by the Neolithic technology of stone-napping. At the ‘operations’ level, skilled individuals use bones – tools – to shape the major raw material – flint – to produce stone tool artefacts. The stone tool artefacts then had a wider range of uses – preparing skins, weapons and wood. Their production, though involving high levels of skill, appears simple in organisational and material terms.

However, this ‘simplicity’ may be more the product of examining a simple context – here, routine production of the artefact. Other elements of the technology complex will be ‘active’ and apparent if non-routine changes in the production and use of the artefact are studied.

An excellent example of this is the account by the anthropologist Sharp of the effect of the introduction of steel axe-heads into Stone Age Aboriginal society (Sharp 1952), which reveals the complex interrelationship between artefacts, social structure and culture.

In this patriarchal society, male heads of households buttressed their social position through their control of the use of stone axes, primarily through the limitation of access to young males and women. The indiscriminate distribution of steel axe heads to young males and even women by western missionaries disrupted this balance of power within the tribe.

Steel axes wore away more slowly than stone axe heads and this physical property helped to disrupt the trading patterns that connected north and south Aboriginal tribes. The raw material for making axes existed in the south and it was progressively exchanged through a network of tribes for goods and materials from the tropical north. The annual gatherings when exchange took place had ritual, quasi-religious significance as well as economic exchange significance, but the arrival of steel axes removed the necessity to meet on the old basis and so undermined the cultural aspects of the annual ritual meetings. In these ways society and culture were disrupted by a change in the material of an important artefact.

When changes to stone axe technology were made the subject of enquiry it was clear that stone axe technology was not ‘simple’ in its social context. Within the society that generated and used this technology the artefact had complex significance that involved many elements of the technology complex for its description.

The technology complex warns us that what appears to be a simple technology may be simple only through the construction of the case analysis. ‘Simple’ here means describable through only a few of the elements from the technology complex.

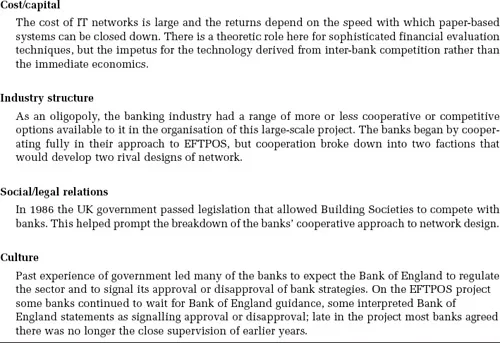

Modern technologies are obviously more complex at the level of the artefact and organisation and they are sustained within a more complex society. As in the stone technology example, the study of their routine use is likely to yield relatively more simple descriptions than the study, for example, of the social process of their generation or implementation. An example of the latter is the account by Howells and Hine of the design and implementation of EFTPOS (Electronic Funds Transfer at the Point of Sale), an IT network, by the British retail banks (Howells and Hine 1993). This found that a complex set of choices of artefacts and social arrangements had to be defined by the banks. These choices ranged across the full range of complex technology elements, as shown in Figure 1.3. Decisions in these categories served to define the technology of the IT network that was eventually implemented.

Figure 1.3 EFTPOS technology as an example of the technology complex (from Fleck and Howells 2001, reproduced with permission of Taylor & Francis Ltd)

The Problem of the Attribution of Causality and the Design of a Study

These examples raise the general issue of how causation should be attributed in accounts of technology development. It is superficially attractive to express this problem in a general way as the issue of how technology and society may relate to each other. In particular the question ‘does technology shape society?’, sometimes described as the issue of technological determinism, has been intensively debated in the history and sociology of technology.4 The technology complex would suggest that a good response to this question is ‘what do you mean by technology?’ For technology should be understood to necessarily include people, so that to ask how technology influences society is to ask how the people organised around a particular set of artefacts influence society. Expressed this way it is easier to see that whether and how technology changes society will depend on the activity of both those most directly attached to the technology, for example through their careers or ownership rights, and those who will be affected more indirectly, by the products or pollution that result from the development of the technology. The question ‘how does technology affect society?’ is only apparently simple, because it is short and is expressed as if there could be an answer with general validity. Any answer depends on the characteristics of both a specific technology and a specific society: there is no general answer.

As part of a collection of writings on this topic of technological determinism (Smith and Marx 1994), the historians Thomas Misa and Bruce Bimber argue that subject discipline and scale of account (Misa) predispose authors to attribute causation in the innovation process quite differently (Misa 1994; Bimber 1994).

A key difference between what Misa calls ‘micro’- and ‘macro’- scale studies is the degree to which the uncertainty of the decision process is captured. ‘Micro-level’ studies of managers’ thought and behaviour, such as that of EFTPOS design and implementation, capture the messiness of real processes of change; the wrong ideas, the misconceptions, the failed bids for competitive change that formed part of the decision process. In contrast, a ‘macro-level’ study of technological change in retail banking over a long time span would find the series of technologies that were actually built – the uncertainty and the alternative paths of development are lost and long-run patterns of change would appear to have their own logic, related to the cheapening cost of computer power over time. Micro and macro studies capture different aspects of the process of innovation and in principle they should complement one another.

To caricature the possible problems of such accounts, unless micro-scale authors import values from outside their studies they may become unable to judge the value of the outcomes they describe – they tend towards ‘relativism’. In contrast, Misa argues that it is those whose research is conducted at the macro level that tend towards overdetermined interpretations of their accounts, for example by attributing excessive rationality and purpose to the actions of actors (Misa 1994: 119). His example is the business historian Alfred Chandler’s interpretation of the Carnegie Steel Company’s vertical integration through the purchase of iron ore deposits. Chandler imputes a defensive motivation to vertical integration, a desire by Carnegie to defend his company against new entrants (Misa 1994: 12). Misa’s micro-analysis of the decision to integrate vertically reveals that Carnegie and his partners were long reluctant to buy iron ore properties and did so only when convinced by a middle-rank manager, whose arguments were largely based on the serendipitous profits that he believed would accrue to the company from the purchase of iron ore land – land that had become temporarily cheap as a result of earlier company actions. As Misa comments:

Vertical integration proved economically rational (lower costs for iron ore plus barriers to entry) for Carnegie Steel, but it was a two-decade-long process whose rationality appeared most forcefully to later historians and not to the actors themselves. (Misa 1994: 138)

With a broad concept for technology such as the technology complex, or Misa’s essentially similar ‘sociotechnical networks’ (Misa 1994: 141), the effort to use and mix different types of account of technology development can be expected to generate many similar problems of interpretation.

Technology, its Uses and the Institutions of the Market Economy

The very term ‘technology’ implies usefulness of some kind, for someone, most obvious at the level of the artefact, an object by definition given form by humankind and whose creation necessarily implies some human purpose, some human use. Innovation in its widest sense is then some change in the way technology relates to its uses. The questions this formulation begs are of social context – useful how and to whom?

This book begins by following the convention that ‘management studies’ should be concerned with organisations operating within the market economy and in recent periods of time, a convention that follows the incessant demands for the subject to be immediately relevant to management practice. There is nothing wrong with such a demand in itself, but it does risk that we take the organisation and performance of the market economy for granted and forget that this is only one way of organising society and technology. One of the standard economics texts defines a market economy as one in which ‘people specialise in productive activities and meet most of their material wants through exchanges voluntarily agreed upon by the contracting parties’ (Lipsey 1989: 786). This clarifies the nature of the economic motivation for technology development for those directly dependent on the market economy for their financial resources – to improve, or to add to the stock of market tradable goods and services. Yet it ignores the institutional arrangements that are essential to a functioning market economy.

Institutions and state policy have always been central to the subject of political economy, and economic and business history have always found room to include the origin and development of such institutions as industrial investment banks and technical education. There is a tendency for the importance of such institutions to be rediscovered by subjects once narrowly conceived: the economics of innovation expanded its scope to include institutions and state policy in the 1990s, as symbolised by the publication of a collection of essays on National Innovation Systems (Nelson 1993); Whitley has similarly sought to expand the scope of organisational sociology in a series of edited essay collecti...