- 224 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Shopping Experience

About this book

This shrewd and probing book seeks to theorize shopping as an autonomous realm. It avoids the reductionist characteristics of economics and marketing. At the same time it avoids the moralizing tone of many contemporary discussions of shopping and consumption. It also contains an appendix which gives a brief history and selected literature of shopping.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1

IN DEFENCE OF SHOPPING

Shopping

This is a defence of shopping. Particularly, it is a defence of women’s shopping, of the time they take over it, and the amount of money they spend on it. It is meant to rebut the ideas that men have about shopping as an activity and to indict a consumer theory that demeans consumer choice. To make the counter-attack I will mention some well-known weaknesses of consumer theory, which is, after all, a one-sided theoretical approach to shopping with crashingly obvious limitations.

Economics and market research are good at explaining the influence of the market on consumers’ choices. The basis for that achievement was laid in the nineteenth century with the theory of utility. But nowadays the really difficult problem is the other way round. We need to understand the influence of the consumer on the market. To approach the current question, the effect of the consumers’ tastes on markets, the idea of the consumer has to be re-examined. How homogeneous is the consumer’s choice? Or how superficial? How episodic and disconnected from her deeper interests? Why do we suppose that she has any deeper interests than shopping? The very questions, as formulated within the current psychological paradigms, are surprisingly insulting to the intelligence of the shopper, who is, after all, the sovereign rational consumer.

One popular explanation presents the shopper as essentially reactive: she reacts to swings in fashion even more than she reacts to market prices. Swings and prices are the two explanations of shopping; by implication, if the shopper’s actions are determined by market or fashion, the decisions are mechanical, not worth further examination. There is a respectable literature on hem-lines in this vein. Let us turn to the historical case of Edwardian trouser legs, getting narrower and narrower and then suddenly widening. An apocryphal story favoured in the retail market is that the Prince of Wales, before he became King Edward VII, fell one day into a pond and ruined his trousers; he was forced for the only time in his life to buy a ready-made pair. This did not fit the royal leg so well as those produced by the Court tailor. The politeness of courtiers made loose trousers the height of fashion. The prince’s mishap provided the occasion for a swing that was bound to happen anyway. The tube-like Edwardian fashion was facing a point of no return as the tube got narrower and narrower. Eventually the boundary between trousers and hosiery would have to go under (to the professional loss of tailors), or trousers would have to get wider. ‘Never trust a man in baggy trousers’, my father was warned by his aged Cambridge tutor. If he thought to arrest a trend, the tutor was wildly optimistic, Oxford bags were to win the day.

If there is a pendulum, it is going to swing first one way and then another. But what kind of explanation is it that predicts change but cannot say when or what the change will be? Not everything changes; some fashions stay stable for many generations. Swings of the pendulum have not affected the design of standard knives and forks, used on standard tables on standard plates. It takes an antiquarian expertise to date them. Other civilizations – Ethiopian, Indian – eat elegantly without either knives or forks. Why has their pendulum not swung our way in the matter of forks, or why have we not swung into an anti-fork mode? The fact is that the swings theory explains very little.

Its supporters qualify it by claiming that only certain choices are subject to swings. The explanation works with an implicit division between purchases based on rational choice, and an optional element, for example everyone might need a coat, but the colour is optional and liable to swings toward the colour of the year. The implication is that some choices are central and steady, others are peripheral and transient, some have to do with internal, others with external matters, some are about necessaries, others about luxuries or surface decoration. Without some such division between choices, the swings model of the consumer would be absurd.

Style

A contrast of intrinsic/extrinsic features saves the swings theory and is congenial to a widely accepted idea of style as to how a work is done, as distinct from what it is. This theory of style implies some essence which can be separated from its appearance; the style is the external surface of a work of art, the polished smoothness or the rough graininess, the surface, extrinsic to the work itself. The theory stops further analysis by the implicit notion that everything has a hidden essence. There is always a reality which the appearance of the thing does not immediately reveal, something inaccessible. This aesthetic philosophy has been thoroughly denounced by Nelson Goodman (1978). If it is misleading in art history, it is pernicious in the theory of consumption. It encourages us to wave away possible reasons for consumer behaviour as inherently unknowable. Always be wary of a model of the human mind which brackets off large areas as irrational or unknowable; the conversation-stopper is also a thought-stopper. Ask instead the common-sense question: Why should people adopt a style that has nothing to do with their innermost being? Or, how could a person reserve his or her innermost being from influencing his or her regular choices? Or, ask what determines the part of human behaviour that belongs to the irrational periphery? What is the part that belongs to the ineffable inner centre? Consumer theory needs either to answer these questions, or to improve its idea of the human being. This improvement, I suggest, can be made by taking seriously culture as the arbiter of taste.

Market forces go some way to reinforce the swings model by identifying certain parts of consumer behaviour as more responsive to prices than free to follow styles. Changes in technology, new openings for labour, changes in production, these all produce price changes to which the consumer is more sensitive than to fashion. The postal zip code, for example, reveals the lifestyle of the consumer because choice of location responds to a set of market constraints. A given locality affords multiple opportunities connected with the engagement of the householder in the labour market. On the consumption side, if an urban area is so densely populated that there are no gardens, then there will be no call for lawn-mowers, pesticides, garden furniture, hoses or sprinklers. A huge bundle of choices tied to the postal zip code are made coherent by reference to market forces. But there are ups and downs of taste which cannot be accounted for by market changes. Even swings theory cannot explain a recent change in attitude to pesticides. It is part of a cultural change, whatever that is.

We have identified some things that are wrong with present paradigms of consumption. It is wrong to suppose that some choices, because they are not obviously responsive to the market, are trivial. It is equally wrong not to take account of the responsiveness of market forces to consumer choice. Above all, it is wrong to consider the consumer as an incoherent, fragmentary being, a person divided in her purposes and barely responsible for her decisions, dominated by reaction to prices, on the one hand, and to fashionable swings, on the other. Does she have no integrating purposes of her own?

Protest

I argue that protest is the aspect of consumption which reveals the consumer as a coherent, rational being. Though intergenerational hostility is important, consumption is not governed by a pattern of swings between generations. Even between generations, consumption is governed by protest in a much more profound and interesting way. Protest is a fundamental cultural stance. One culture accuses others, at all times. Instead of the weak notion that some choices among consumer goods are acts of defiance, I would maintain much more strongly that consumption behaviour is continuously and pervasively inspired by cultural hostility. This argument will reinstate the good sense and integrity of the consumer.

We have to make a radical shift away from thinking about consumption as a manifestation of individual choices. Culture itself is the result of myriads of individual choices, not primarily between commodities but between kinds of relationships. The basic choice that a rational individual has to make is the choice about what kind of society to live in. According to that choice, the rest follows. Artefacts are selected to demonstrate the choice. Food is eaten, clothes are worn, cinema, books, music, holidays, all the rest are choices that conform with the initial choice for a form of society. Commodities are chosen because they are not neutral; they are chosen because they would not be tolerated in the rejected forms of society and are therefore permissible in the preferred form. Hostility is implicit in their selection:

‘I can’t stand that ghastly orange colour on the walls,’ says the unhappy tenant of a public housing unit (Miller, 1991). She knows perfectly well that a neighbour appreciates that vivid orange colour for its brightness. The colour is implicated in her neighbour’s lifestyle. Why does she not paint it over in a decent creamy beige? The anthropologist thinks that she does nothing to remove the thing she hates because she is alienated from the council estate she lives in. Yes, and it might be a positive value for her to have a colour on the wall that she considers ghastly, a reminder of the war against the others and their despised way of life, on behalf of herself and hers. What colours did she wear? No shopper himself, the anthropologist does not report on her other antipathies.

‘I wouldn’t be seen dead in it,’ says a shopper, rejecting a garment that someone else would choose for the very reason that she dislikes it. The hated garment, like the hairstyle and the shoes, like the cosmetics, the soap and toothpaste and the colours, signals cultural affiliation. Because some would choose, others must reject. Shopping is reactive, true, but at the same time it is positive. It is assertive, it announces allegiance. That is why it takes so much deliberation and so much time, and why women have to be so conscientious about it, and why it gives them so much satisfaction. That is why men are wise to leave shopping to their wives. Anyway, men’s clothing and hairstyle is much more highly prescribed by the occupational structures in which they spend so much of their lives; they are not sensitized to such a wide diversity of signals. And the fact that men stand outside these arenas of cultural contest explains why they are surprised that things are so costly and why it is difficult to explain to them that so much is at stake. At the beginning of utility theory there were alleged preferences, then there was the indifference schedule. What has been missing all along is a scale of hostility between cultures. Inquiries about consumption patterns have focused on wants. The questions have been about why people want what they buy, whereas, most shoppers will agree, people do not know what they want, but they are very clear about what they do not want. Men, as well as women, are adamant about what they do not want. To understand shopping practices we need to trace standardized hates, which are much more constant and more revealing than desires.

Four cultural types

Cultural theory can explain how hates get to be standardized. It assumes four distinctive ways of organizing; four cultures which are each in conflict with the others. Choosing commodities is choosing between cultures, choosing one and rejecting the others. The four types are as follows. One is an individualist lifestyle, driving in the fast lane, as the advertisements say. It is a choice for a competitive, wide-flung, open network, enjoying high tech instruments, sporty, arty, risky styles of entertainment, and freedom to change commitments. In choosing this, the individualists reject the three other styles. One of these is the hierarchical lifestyle, formal, adhering to established traditions and established institutions; maintaining a defined network of family and old friends. (This is definitely driving in the slow lane: it only seems to be a thriftier lifestyle; it costs a lot to maintain the family network, so there is not much cash left for the high tech, travel, entertainment, and so on.) The other lifestyle rejected both by the individualists and by the hierarchs is egalitarian, enclavist, against formality, pomp and artifice, rejecting authoritarian institutions, preferring simplicity, frankness, intimate friendship and spiritual values. Finally, there is a fourth type of culture recognized by cultural theory, the eclectic, withdrawn but unpredictable lifestyle of the isolate. Whatever form it takes, it escapes the chores of friendship and the costs imposed by the other types of culture. The isolate is not imposed upon by friends, his time is not wasted by ceremony, he is not hassled by competition; he is not burdened by the obligatory gifts required in the other lifestyles, nor irked by tight scheduling: he is free. Or you could say, in another frame of reference, that he is alienated.

Anthropologists have been interested in cultural strategies as a defence against the possibility of alienation.1 This argument is on the same lines: there is a defensive element, also an element of attack, not against alienation necessarily, but against the rejected cultural forms. Alienation from one culture does not necessarily leave a person stranded; there are other cultural options. The option for punk culture is a rejection of the mainstream cultures, true enough, but rather than an opting out of culture as such, it is a creative cultural strategy in its own right. An isolate is not necessarily alienated in a general way; he can be quite benign in his attitudes to the cultures he does not want to adopt.

None of these four lifestyles (individualist, hierarchical, enclavist, isolated) is new to students of consumer behaviour. What may be new and unacceptable is the point that these are the only four distinctive lifestyles to be taken into account, and the other point, that each is set up in competition with the others. Mutual hostility is the force that accounts for their stability. These four distinct lifestyles persist because they rest on incompatible organizational principles. Each culture is a way of organizing; each is predatory on the others for time and space and resources. It is hard for them to co-exist peacefully, and yet they must, for the survival of each is the guarantee of the survival of the others. Hostility keeps them going.

Let me pause to illustrate the inherent conflict between cultures. Consumption has been defined by the image of the household shopping basket. Whatever comes home from the shops is designated for use in specific spaces and times. The fast-lane individualist culture is driven by the principle that each person should expand his/her network of alliances. It is hard to do this in a hierarchical household without tearing up the fences and intruding into the reserved times and spaces needful for the hierarchist’s lifestyle. The hierarchical and individualist principles are at war, each contemptuous of the other, each seizing a victory where it can. This basic incompatibility lies behind the conflict between generations, and specially between mother-in-law and daughter-in-law, since there is a movement towards hierarchy with advancing age. It would not suit either the hierarchist or the individualist to have the household turned into an egalitarian commune. The isolate tries to avoid alignment, and in doing so gives offence to all, for it is difficult to back out of the cultural conflict going on in any home.

The myths of nature

Anyone reading this can recognize it, and anyone can see that if there is a constant pressure to define allegiance to one or another of these four conflicting cultures, it will go a long way to explain shopping. But so far it sounds didactic and a priori. The theory is that cultural allegiance pervades all behaviour, including shopping. The consumer wandering round the shops is actualizing a philosophy of life, or, rather, one of four philosophies, or four cultures. The cultural bias brings politics and religion into its embrace, aesthetics, morals, friendship, food and hygiene. According to the theory in its strongest version, the idea of the consumer as weak-minded and easily prevailed upon is absurd. Only consider the turning away from pesticides, and the turning away from aerosols, artificial fertilizers and carnivorous diets, and consider the great interest shown in the source of energy, whether powered by nuclear or solar energy or by fossil fuels. These examples of consumer preferences are not responses to market conditions. Quite the contrary: they bid fair to change markets profoundly. The consumer has become interested in the environment. But this interest is not uniform. The consumers are found in all four cultural corners: some are in favour of cheap fuel, including nuclear power; others are against it and focus more upon conservation of energy; others simply do not care.

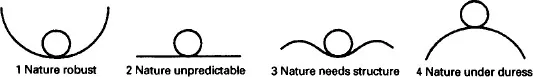

Michael Thompson has led the way in applying cultural theory to the confused and stormy debates on environmental policy (Schwartz and Thompson, 1990; Thompson, 1988; Thompson et al., 1986). In what follows I attempt to apply his method to consumer theory. Thompson’s method is to hearken attentively to the debates on the environment and to extract the basic assumptions from their arguments. Infinite regress reaches no conclusion. Eventually explanations must come to an end. Thompson hears the different strands in the environmental debates making appeal to the way that nature is. Nature, being this way or that, can only support this policy or that, and ruin will follow inexorably on failure to recognize what nature is like. He tracks down four distinctive myths of nature (Thompson et al., 1990). Each is the account of the world that will justify the way of life to which the speaker is committed. The commitment is not a private intention. It is part of the culture with which the speaker has chosen to be aligned. Thompson illustrates the four myths of nature with four diagrams from equilibrium mechanics (see Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Myths of nature (Schwartz and Thompson, 1990)

- Nature is robust. This version justifies the entrepreneur who will not brook his plans being blocked by warnings that carbon dioxide pollution or soil erosion may cause irreversible damage. His cultural alignment is to a way of life based on free bidding and bargaining. He needs nature to be robust to refute the arguments of those who are against the transactions he has in mind.

- Nature is unpredictable. There is no telling how events may turn out. This version justifies the non-alignment of the isolate. He uses it as his answer to attempts to recruit him to any cause.

- Nature is robust, but only within limits. This is the version that issues from the hierarchist...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Figures

- Notes on Contributors

- Acknowledgements

- Introduction

- 1 In Defence of Shopping

- 2 Could Shopping Ever Really Matter?

- 3 Women, the City and the Department Store

- 4 Supermarket Futures

- 5 The Making of a Swedish Department Store Culture

- 6 Shopping in the East Centre Mall

- 7 Shopping, Pleasure and the Sex War

- 8 The Scopic Regimes of Shopping

- Appendix Research on Shopping – A Brief History and Selected Literature

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access The Shopping Experience by Pasi Falk, Colin Campbell, Pasi Falk,Colin Campbell in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Sociology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.