- 256 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Youth Justice and Social Work

About this book

It is vital for social work students and practitioners to understand the complexities of the youth justice system. This fully revised second edition analyses and puts into context several pieces of new legislation such as the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008, the Youth Rehabilitation Order 2009 and the new Youth Conditional Caution. Carefully selected case studies and summaries of contemporary research help to underpin this accessible and essential resource. Ideal for students on placement, this new edition enables the reader to follow complex and often difficult legislation and law.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Youth Justice and Social Work by Jane Pickford,Paul Dugmore,SAGE Publications Ltd in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Social Work. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1 Values, Ethics and Human Rights Issues in Youth Justice Social Work

Achieving a Social Work Degree

This chapter will help you begin to meet the following National Occupational Standards.

Key Role 6: Demonstrate professional competence in social work practice.

- Work within agreed standards of social work practice and ensure own professional development.

- Manage complex ethical issues, dilemmas and conflicts.

It will also introduce you to the following academic standards as set out in the social work subject benchmark statement:

5.1.1 Social work services, service users and service carers.

5.1.3 Values and ethics.

Problem-solving skills.

5.5.3 Analysis and synthesis.

5.6 Communication skills.

5.7 Skills in working with others.

Part One: Understanding Ethical Dilemas between Legal and Social Work Practice in Youth Justice

Jane Pickford

Introduction

The youth justice system in England and Wales caters for young people who get into trouble with the police who are aged between 10–17 (inclusive). Youth justice practice is unlike any other area of social work because your client, no matter how harsh their background, will be viewed primarily as a wrongdoer who deserves to feel the weight of legal powers pressing against them. When this force is applied, you may find that some of the caring precepts of your profession become challenged, diluted and on occasion, negated.

Consequently, the discord between social work ethics and legal principles is perhaps no more keenly felt than in work with juvenile suspects and law-breakers. In some instances welfare instincts that practitioners are trained to develop within a culture of safeguarding and child protection, hit a legal brick wall when confronted with principles of justice and victims’ rights.

In the first part of this chapter, you will be introduced to the ethical conflicts involved in youth justice social work. This will include examining dominant concepts of childhood that have undoubtedly impacted upon our juvenile justice system, explaining the traditional conflicting theories of youth justice and of criminology, as well as analysing how our youth justice system fares when faced with moral and legal standards imposed by international conventions and human rights legislation. In addition, it will be useful to outline statistics in relation to trends in youth offending, risk factors and custody rates, in order to contextualise our investigations.

The second part of the chapter provides an examination of the values and ethics underpinning social work practice and the regulatory frameworks in place to ensure practice is in accordance within the values and ethics fundamental to the social work profession. It considers the application of social work values to practice and potential ethical dilemmas facing social workers in their practice with children and young people who offend.

But first, let's introduce the nature of the big ethical problem for youth justice practitioners.

The ‘Big Dilemma’ in Youth Justice

Are children born innocent and become corrupted by exposure to the adult world and so need protection, or are children born with the potential for evil and so need to be controlled and civilised by adults? This fundamental question that is at the core of the nature vs nurture debate (which perhaps cannot be answered, even with the wealth of biological, psychological and environmental research gathered over the history of criminological investigation) is one of the most potent ethical dilemmas you will encounter in youth justice practice. It relates to the divergent approaches that have developed in relation to models for dealing with young offenders.

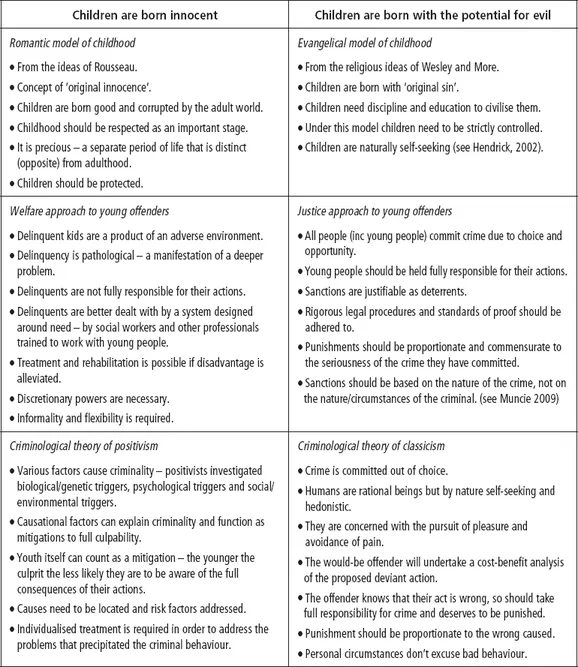

Though many academics assert that it might now be old fashioned to analyse tensions between the two historically dominant perspectives of welfare vs justice, it is evident to practitioners that these tensions are at the root of differences of opinion in public, professional and political arenas, when deciding how to deal with children and young people who come before the criminal justice system. Though these approaches (and others that have developed) will be examined later in this chapter and in detail in Chapter 2, it is useful to briefly outline them here and analyse how they interact with models of childhood (see Hendrick, 2002m) and two mainstream criminological theories. Figure 1.1 attempts to simplify the polemic dominant theories of childhood, youth justice and criminology and highlight how they interact and overlap.

Examining Figure 1.1, it is clear that (i) the main perspectives of childhood, (ii) the dominant theoretical approaches to young offenders, and (iii) mainstream criminology, all share characteristics and are mutually supporting. The romantic model of childhood has a lot in common with the welfare approach to youth justice which in turn shares similarities with the school of positivism within criminology. Whereas, the evangelical model of childhood is reflected in the justice perspective of youth offending, which is in turn supported by the classical school of criminology. However, it is also clear that these two sets of three mutually supportive approaches are arguably oppositional polemic positions, and herein lies the ‘big dilemma’ in youth justice practice. The inability of successive governments (and indeed public opinion) to clearly recognise this dilemma and choose between these fundamentally different ways forward, continues to cause tensions within youth justice practice. Due to the elemental nature of this question, the polemics it raises and the fact that it taps into deep-seated and perhaps irresolvable academic arguments surrounding the nurture vs nature debate, it is doubtful that we will find any resolution to this issue.

Trends in Youth Offending

In order to conceptualise the youth crime problem, it is useful to examine the nature and extent of juvenile law breaking. Statistics indicate that during the period 1992 until 2003, there was a significant decline in detected juvenile criminality. Over that period, the total youth offending dropped by 27 per cent, despite public perceptions to the contrary (NACRO, 2009). However, the period from 2003–2007/8 witnessed an apparent reversal of that trend, with overall youth crime rising.

The apparent rise in detected youth crime over those years was probably influenced by issues other than the actual rate of youth criminality. It has been acknowledged by academics and practitioners that changes in police practice probably impacted on crime figures, creating misleading statistical data about seeming rises in juvenile law breaking. In 2002, the Labour government set a target (eventually of 1.25 million) for the police to narrow the ‘justice gap’ (between offences recorded and those ‘brought to justice’) by increasing the number that result in ‘sanction detection’ (i.e. by obtaining convictions or by issuing penalty notices for disorder (PNDs) or obtaining confessions from existing offenders of previous offences to be taken into consideration (TICs) when sentencing a current offence or by issuing reprimands and final warnings). One possible consequence is that offences which would previously have been dealt with informally (and go unrecorded) might have received a formal response over that period and so be reflected in the recorded figures for youth crime. Further, the increased use of anti-social behaviour orders (ASBOs) and the consequent criminlisation of those who breached orders arguably similarly and misleadingly inflated the statistics (NACRO, 2009).

The increase in ‘sanction detections’ was not followed by a concomitant increase in the police clear-up rate. Bateman's analysis of the seeming rise in detected youth crime was that it was a function of sanction detections being imposed for behaviour that would previously not have attracted such an outcome (Bateman, 2008).

The target was, in other words, met at the expense of those populations of offenders who might otherwise have received an informal response for minor transgression against the law (NACRO, 2009).

These would include:

- offences committed by younger people;

- less serious offending;

- offences committed by girls.

Analysis of the data confirms that the apparent rise in juvenile criminality 2003–2007 can be substantially explained by disproportionate rises in each of the above categories. It seems that the police were picking low-hanging fruit – those easiest to pursue – when attempting to meet government targets over this period. Once the targets were removed, declines in overall youth crime, particularly in relation to first offenders, were notable.

Youth crime figures peaked in 2007/8 and since that period total offences committed by young people has notably declined, largely due to a reduction of first time entrants into the youth justice system (i.e. those receiving their first reprimand, final warning or conviction (Department of Education, 2010; Youth Justice Board/Ministry of Justice, 2011)).

Activity 1.1

Take a look at the most recent statistics relating to youth crime at the Ministry of Justice website: www.justice.gov.uk and outline the current trends in youth crime. Has the crime rate for 10–17 year olds risen or fallen over the last few years? What factors might have precipitated recent trends? Have there been any noticeable patterns in increases or decreases of particular types of crime?

If we analyse some of the key data published jointly by the Youth Justice Board and the Ministry of Justice early in 2011, the downwards trend is clear:

- There were 198,449 proven offences committed by young people aged 10–17 which resulted in a disposal in 2009/10 – this is a decrease of 19% from 2008/09 and 33% from 2006/07.

- The most common offences resulting in a disposal in 2009/10 were:

- – theft and handling – 21% of all offences;

- – violence against the person – 20% of all offences;

- – criminal damage – 12% of all offences.

- In 2009/10 most youth offending in England and Wales was committed by young men – 60% of all offences were committed by young men aged between 15 and 17 years. Young males were responsible for 78% of the offences committed by young people.

- There were 155,856 disposals given to young people in 2009/10. This is down 28% from 2006/07.

- These falls followed a period of rapid growth from 2003/04 to 2007/08, when out of court disposals almost trebled.

- This increase was due to the introduction of Penalty Notices for Disorder (PNDs) which coincided with the introduction of a public service agreement target, which took effect in 2002, to increase the total number of offences brought to justice (OBTJ). This target has now been removed.

- Females accounted for 22% of all disposals given to young people in 2009/10. They accounted for 32% of all pre-court disposals given, and 17% of all first-tier disposals. They accounted for 15% of all community disposals and only 8% of custodial disposals.

(Youth Justice Board/Ministry of Justice, 2011)

Trends in Custodial Sanctions

In England and Wales we lock up more children and young people than almost any other Western society. NACRO (2010) in a policy position paper recommending further reductions to the amount of children and young people being sent to the secure estate, made the following comments on custodial remands and disposals:

- Between 1992 and 2002, the number of young people sentenced to custody rose by more than 85% while the level of detected youth crime reduced by more than a quarter.

- During the early months of 2009, the population of the secure estate fell for the first time since 2000 – this trend has continued and early 2011 there are approx 2,100 young people in the secure estate – at its peak it reached approx 3,000.

- In England and Wales we incarcerate four times more under 18s than France, ten times more than Spain and 100 times more than Finland.

- Custody is costly but has an appalling success rate (75% are reconvicted within one year) and academic evidence suggests that for many young people the use of custody actually increases the risk of reoffending.

- Reoffending following release from custody is inversely related to age: younger children are more likely to be reconvicted than older teenagers, who in turn are more likely to be reconvicted than adults (NACRO, 2010, p2).

- A large number of young people who are detained in custodial facilities do not pose a serious risk to the public.

- Of young people aged 16 to 17 convicted of non-violent offences, 12% are given custodial sentences, while over a third of younger children below the age of 15 in custody do not seem to meet the statutory criteria for incarceration.

- Around 40% of the population of the secure estate for children and young people are classified as vulnerable and one third of children have no educational provision on entering those establishments.

(NACRO 2010)

Risk Factors and Youth Offending

The Youth Justice Board highlighted the following four risk factors as being the most influential on youth offending:

- Family e.g. inadequate, harsh or inconsistent parenting.

- School e.g. low achievement, disaffection, truancy or exclusion.

- Community e.g. residence in areas of low community cohesion, crime hot spots or easy access to drugs.

- Personal e.g. being male, mixing with offending peers, poor physical or mental health or misuse of drugs or alcohol.

(Youth Justice Board, 2005b)

To these four major influences, Pitts (2008) possibly adds a fifth (though linked to the factor of community) namely, physical area. When investigating gang activity, Pitts discovered that youth involvement in serious criminality correlated more strongly with habitation in deprived neighbourhoods than with the other factors noted above.

These vulnerability/susceptibility factors are at the centre of risk assessments undertaken by Youth Offending Teams (YOTs) across England and Wales. The Youth Justice B...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Series Editors' Preface

- Introduction

- Chapter 1 Values, Ethics and Human Rights Issues in Youth Justice Social Work

- Chapter 2 The Development of Youth Justice Philosophies, Laws and Policies

- Chapter 3 Criminological Theories in Relation to Young People who Offend

- Chapter 4 The Laws and Sentencing Framework of Contemporary Youth Justice Practice

- Chapter 5 Working within a Youth Offending Team and in the Youth Justice System

- Chapter 6 Assessing Young People

- Chapter 7 Working with Young People

- Chapter 8 Looking Forward: Developing your Career and Proposed Youth Justice Reforms

- Conclusion

- Appendix: Subject Benchmark for Social Work

- References

- Index