- 384 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

The Development of Working Memory in Children

About this book

Using the highly influential working memory framework as a guide, this textbook provides a clear comparison of the memory development of typically developing children with that of atypical children. The emphasis on explaining methodology throughout the book gives students a real understanding about the way experiments are carried out and how to critically evaluate experimental research.

The first half of the book describes the working memory model and goes on to consider working memory development in typically developing children. The second half of the book considers working memory development in several different types of atypical populations who have intellectual disabilities and/or developmental disorders. In addition, the book considers how having a developmental disorder and/or intellectual disabilities may have separate or combined effects on the development of working memory.

The Development of Working Memory in Children is for undergraduate and postgraduate students taking courses in development/child psychology, cognitive development and developmental disorders.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Development of Working Memory in Children by Lucy Henry in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Psychology & Educational Psychology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

The Working Memory Model

Introduction to the working memory model

Key features of the working memory model – an overview

The phonological loop

Evidence in support of the phonological loop

The visuospatial sketchpad

The central executive

The episodic buffer

Overall summary

Further reading

Learning outcomes

At the end of this chapter, you should have an understanding of the original and revised versions of the ‘working memory model’ (Baddeley, 1986, 2000, 2007; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974). This has been a dominant model of memory in recent decades and represents a key approach to understanding the development of memory in children with and without developmental disorders. Once you have read this chapter, you should be able to: (1) describe each of the four components of the revised working memory model; and (2) outline some of the key evidence supporting the structure of each component.

Introduction to the working memory model

The working memory model is a very influential theory of memory designed to account for how we temporarily manipulate and store information during thinking and reasoning tasks. The model helps us to understand how memory processes are used during day to day familiar activities, or during more demanding tasks that require greater effort and new thinking (perhaps a problem-solving task that has not been encountered before). One way of understanding working memory is to consider the types of memory we need while we read, plan future activities, do the crossword/Sudoku, or follow the news headlines.

One of the important concepts to understand about working memory is that it is limited in capacity, which means that we cannot store and manipulate endless amounts of information. Therefore, the types of thinking and remembering tasks we can undertake will be constrained by working memory resources. Working memory also limits, to some degree, the types of things we can handle concurrently. Whilst there are some types of tasks that can be carried out at the same time, other types of tasks compete for the same resources within the working memory system and, therefore, interfere with each other.

Working memory is vital because it underpins abilities in many other areas such as reasoning, learning and comprehension. In the most recent description of the working memory system, Baddeley (2007) even attempts to use his model to account for consciousness!

The working memory model is used in this book as the theoretical underpinning for our discussion of memory development in typical and a typical children. There are three major reasons for choosing the working memory model for this purpose. First, the working memory model has become a major explanation for memory and thinking in recent years and has received wide support. Secondly, using one unified theoretical framework makes it much easier to compare memory development in children with typical development to those who have various types of developmental disorders (i.e. a typical development). The final reason for using the working memory model as the theoretical foundation in this book is its comprehensiveness and clear four-part structure, which accounts for many different types of remembering. The four-component structure of the working memory model provides not only theoretical sophistication, but an organisational template for every chapter in this book. Each chapter is organised around the four components of the working memory model, making it easier for readers to navigate through the research and see how development differs in typical and a typical children.

This chapter provides a description of each of the four main components of the revised working memory model and covers some of the key psychological evidence presented to support the model. However, this is not an exhaustive account of the working memory model, but rather an overview, covering the main points in enough detail so that you can understand the rest of the book. If you would like more information on the working memory model, including evidence concerning neuroimaging and neuropsychological studies, please look at the Further reading section at the end of this chapter.

Note that the next chapter (Chapter 2) provides detailed descriptions of the most common ways in which working memory has been measured in typical and a typical children/populations. Chapters 3 and 4 are devoted to the development of working memory in typically developing children. Chapters 5 to 8 go on to consider the development of working memory in children with a typical development. As already noted, every chapter adopts the same general structure. Each area of working memory is discussed in turn with respect to the population of children under discussion.

For now, however, we return to the central issue of the current chapter, providing an introduction to the working memory model.

Key features of the working memory model – an overview

This section provides a brief overview of the key features of the ‘original’ working memory model (Baddeley, 1986; Baddeley & Hitch, 1974) and the ‘revised’ working memory model (Baddeley, 2000, 2007). In most respects, the revised working memory model simply adds to the original, but there are some changes to individual components that will be pointed out. The sections following this overview will describe each component of the model in more detail, and present some key experimental evidence to support the proposed structure of working memory.

To start to understand what working memory is, it is useful to examine a quote from Baddeley (2007), in which he describes working memory as follows:

… a temporary storage system under attentional control that underpins our capacity for complex thought. (p. 1)

There are several important points even in this one short sentence. First of all, the system deals with temporary storage and so deals with things we are doing right now. Secondly, the system is under attentional control, indicating that, in most instances, we choose where to direct our attention. Finally, the system underpins our capacity for complex thought, making it fundamental for any type of higher order thinking or reasoning task. In this way, working memory can be viewed as the bedrock for virtually all thinking processes (often described as ‘cognitive’ processes) that rely on temporary memory storage. We will not go into the history of why this model was proposed as this is readily available in any of Baddeley’s very readable books about working memory (see Further reading at the end of the chapter).

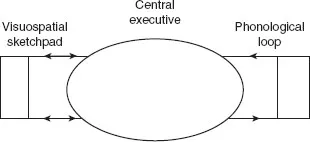

The original working memory model (Baddeley & Hitch, 1974) consists of three components. The most important component is a system for controlling attention, known as the ‘central executive’. This is used to ensure that working memory resources are directed and used appropriately to achieve the goals that have been set. There are also two temporary storage systems. One of these is for holding speech-based information and it is known as the ‘phonological loop’. The second storage system is for holding visual and spatial information and it is known as the ‘visuospatial sketchpad’. These two storage mechanisms are regarded as ‘slave subsystems’, because they do not do anything beyond holding information in a relatively passive manner. The real ‘brains’ of the working memory system is the central executive. Figure 1.1 below illustrates the original working memory model.

Figure 1.1 The original conceptualisation of the working memory model

Source: Reproduced with permission from Oxford University Press (Baddeley, A.D. & Hitch, G.J. (1974). Working memory. In G.A. Bower (Ed.), The psychology of learning and motivation, Vol. 8 (pp. 47–89). New York: Academic Press)

Although the original working memory model was very successful in accounting for a large body of experimental research, various criticisms of the model led to some significant revisions. For example, it became clear that there was a need to account for the effects of long-term knowledge (all of the stored information that we know about the world) on working memory, something that the original model did not take into account.

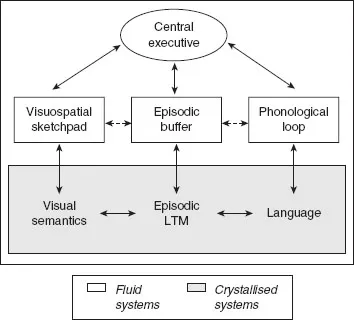

Therefore, Baddeley added a fourth component to the working memory model, the ‘episodic buffer’ (Baddeley, 2000). This new component of working memory provides a number of important new features. First, a link to long-term memory; second, a way of integrating information from all of the other systems into a unified experience; and third, a small amount of extra storage capacity that does not depend on the perceptual nature of the input. Figure 1.2 illustrates the new version of the working memory model, which takes account of the episodic buffer.

Now we will turn to each of the four components of the revised working memory model, looking at each in more detail. We will also consider some of the more important evidence that has been used to support the proposed structure of the working memory model. The relationships between the components illustrated in Figure 1.2 will become clearer as we continue our discussion.

The phonological loop

The phonological loop component of working memory is proposed as a specialised storage system for speech-based information, and possibly purely acoustic information as well. The phonological loop is described as a ‘slave’ sys-tem as it is not ‘clever’ in any way; it does not have any capacity for controlling attention or decision-making. The phonological loop is merely a temporary store for heard information, particularly speech. It represents the storage system responsible for ‘phonological short-term memory’ (PSTM), the ability of individuals to remember small amounts of heard information over short periods of time. This type of memory has been closely studied in adults and children for many years and a large part of this book will be devoted to discussing how PSTM develops in children. Please refer to Chapter 2 for details on how PSTM is measured in typical and a typical populations of children.

Figure 1.2 The revised model of working memory (Baddeley, 2000)

Source: Reproduced with permission from Elsevier (Baddeley, A.D. (2000). The episodic buffer: A new component of working memory? Trends in Cognitive Science, 4(11), 417–423)

The phonological loop is divided into two further subcomponents, both believed to be located in the left hemisphere of the brain according to neuroimaging evidence (Jonides et al., 1998; Paulesu, Frith & Frackowiak, 1993). These two subcomponents are now described.

The phonological store

The first subcomponent of the phonological loop is the phonological store. This is the area of the system in which speech material is held for short periods of time. The phonological store is described as ‘passive’, because it simply holds the information; and ‘time-limited’, because the information fades rapidly. The information in the phonological store is often described as the ‘memory trace’, and the phenomenon of rapid fading is often called ‘trace decay’. Trace decay reflects the fact that representations held in the phonological store are temporary, rather than completely accurate, long-lasting representations of the things we encounter. Trace decay is so rapid in the phonological store that only around two seconds’ worth of speech-based material can be held, perhaps just long enough to hold a telephone number in mind before dialing it.

Although there are long-standing arguments over the whole notion of whether trace decay (or interference) accounts for forgetting in phonological short-term memory (PSTM), we do not have time to go into the detailed arguments here. You can read more about this issue in Chapter 3 of Baddeley (2007) referenced at the end of this chapter.

The articulatory rehearsal mechanism

The second subcomponent of the phonological loop is the articulatory rehearsal mechanism. We have already mentioned the two-second limit on the phonological store. The articulatory rehearsal mechanism is used to recite the information in the phonological store, in order to prevent this very rapid decay. The recitation of the material re-enters it into the phonological store, where it immediately starts to decay again. Baddeley describes the articulatory rehearsal mechanism as like a tape loop or a tape recorder with a two-second duration. The recitation processes can prevent the material decaying, by constantly refreshing it. The process of recitation is called ‘articulatory rehearsal’ or ‘verbal rehearsal’ and is a major strategy used to improve or enhance the capacity of PSTM.

Verbal rehearsal is usually done internally (i.e. you can’t hear a person doing it) by adults, but there are interesting changes in verbal rehearsal in children throughout their development, which we will consider in Chapter 3. There are also arguments over the exact form that verbal rehearsal takes and these revolve around whether real articulation is taking place. However, most researchers would agree that verbal rehearsal involves some form of covert verbalisation (i.e. internal speech) which uses the same speech planning mechanisms that we use for real speech, even if it does not always require actual speech output.

We will consider the issue of verbal rehearsal and articulation further in Chapter 3, when we discuss the development of working memory in typically developing children. For now, Box 1.1 gives an example of how verbal rehearsal may be useful in real life, when good PSTM could prove vital.

Box 1.1 Remembering a car number plate

Witness A has just seen a hit and run driver knock down an elderly pedestrian at a controlled crossing. Knowing that providing a description of the vehicle, and better still the car number plate, is vital, Witness A attempts to remember as much as possible. The car was relatively small, royal blue in colour and had blackened windows and spoilers. Witness A thinks that she could probably remember this information using a vis...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title

- Copyright

- Dedication

- Contents

- Preface

- 1 The Working Memory Model

- 2 How is Working Memory Measured?

- 3 Working Memory and Typical Development: Part 1

- 4 Working Memory and Typical Development: Part 2

- 5 Working Memory in Children with Intellectual Disabilities

- 6 Working Memory, Dyslexia and Specific Language Impairment

- 7 Working Memory in Children with Down Syndrome and Williams Syndrome

- 8 Working Memory in Children with Autism Spectrum Disorders

- 9 Concluding Comments

- References

- Index