![]()

1 | Research for Health Care Practice |

This chapter tells you what research is and explains why your research is important, introduces you to the basics of research and the various ways of undertaking research.

The research approach described and discussed in this book can be used by anyone involved in health care practice within their own health care setting. The research can contribute to the development of health care practice for the particular time and place it was undertaken as well as adding to the wider body of knowledge about health and health care.

Anyone engaged with health care can use the research approach described in this book. This includes people living with long-term health conditions and community groups. People working as health professionals can incorporate this type of research into their day-to-day work, including those who directly care for patients and those managing or planning services.

Research undertaken as collaboration between people using health care services and local health care professionals is ideal as it brings into the research the perspective of those using health care services. However, health professionals have a key role to play in research for health care practice.

Health professionals are well positioned to take the initiative in research. They are often committed to health care for long periods, sometimes all their working life, so research can continue as part of their health care practice in the long term. They are well placed to notice change; for example, the impact of a new diagnostic or treatment technology, changes in the population they serve through migration or change in the local environment. Such changes may be the stimulus for research. Health professionals build up considerable knowledge of their own health care service and the community it serves, including its history, so they can take this into account in their research. They can also continue to observe the impact of change as well as the impact of their own service developments in the long-term.

Research is about the discovery of new knowledge. This includes any study of the natural, social or technical world that increases our understanding of it, and is undertaken in such a way that others can follow how it was done (transparency) and assess the robustness of the results. Research is a global collaborative effort. Every research project, including those undertaken in a specific health care setting, can contribute to the development of new knowledge.

Health professionals contribute to the global research effort

Research can be thought of as many spirals of activity extending through time, with cycles of activity changing over time both locally and globally. Health professionals can contribute to research as part of the global research effort in the same way as academics and full-time researchers. The world is constantly changing, so we need to reinvestigate the world because it has changed. Our new knowledge about the world will itself change something about the world and so prompt further research. This could be in our own local context or more widely. New methods of investigating the world lead to further research as they give us the opportunity to find out more. Individual researchers only contribute to one part of the research spiral. For example, inspired by a need identified by a health professional in their research, an engineer may work on a new technology. This technology may be tested by another health professional for use in health care. A social scientist then studies the impact of this new technology on people’s experience of illness. Understanding the experience of illness may prompt the engineer to modify the new technology or a health professional to review how the technology is incorporated into health care practice.

Most academic and research disciplines have knowledge and expertise relevant to health care. Being part of this multidisciplinary research effort is exciting and challenging but can also feel overwhelming. There is a danger that we ignore unfamiliar academic and research disciplines and assume that all relevant sources of knowledge and expertise for health care research are within the body of expertise we think of as health science or clinical science. We need to find a balance between drawing on the resources of the wider research community and getting on with investigating the health issues that concern us.

Understanding the range of types of research that relate to health and health care helps us to open our minds to knowledge, ideas and possibilities that we may rarely think about in our daily work in health care. The following examples illustrate the range of types of research relevant to health and how they feed into the research spiral. Each example is a patient we could meet in our clinical practice.

An 18-year-old man with insulin-dependent diabetes who has failed to attend follow-up at the diabetes clinic. His last blood test indicated poor control of his diabetes.

Insulin is the key to this man’s survival. To understand the research that led to the clinical use of insulin we have to look back into history. My aim is not to give you all the details of the history but alert you to the many different types of research that contributed over time to its discovery and use.

Diabetes has been known since ancient time. Physicians observed each individual patient as a case study, describing their symptoms in detail. By comparing each case with other cases, they identified the symptoms they had in common as diabetes. In the 18th century, chemistry experiments showed the urine and blood of those with diabetes contained a lot of sugar. In the 19th century, the link was established between the symptoms of diabetes and changes found in the pancreas on dissection of those that had died. Detailed examination of the pancreas revealed the Islets of Langerhans and towards the end of the 19th century, research including animal experiments identified insulin as the key substance. In 1922 the joint work of physiologists and biochemists, with technical help from a pharmaceutical company, led to the isolation of insulin as an extract. This was then tested on a young boy dying of diabetes who survived on continuing insulin injections.

The research disciplines in the front line of this research included clinical research, chemistry, anatomy and pathology, physiology and biochemistry. These were supported by other disciplines including physics and engineering for the development of the microscope and organic chemistry for understanding substances such as proteins.

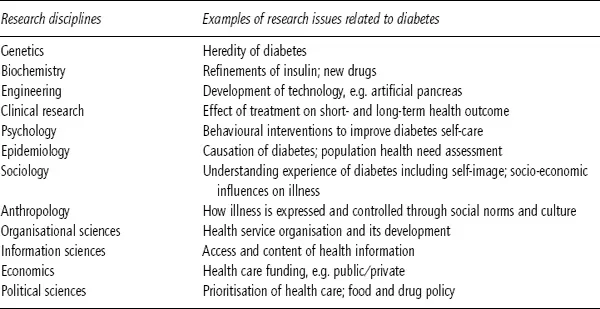

Once people with diabetes were able to survive on insulin, research continued to refine insulin treatments and to seek to understand the cause of diabetes. Epidemiology, the social sciences and behavioural sciences have also contributed to research on diabetes. Table 1.1 gives examples of research related to diabetes currently undertaken by different research disciplines.

Table 1.1 Examples of the diverse research disciplines that contribute to the health care of people living with diabetes

A man in his fifties who has low mood, insomnia, fits of tearfulness and irritability. He has successfully worked for a company at a local manufacturing plant for 10 years. With the shut-down of the local plant he was made redundant. He has a supportive family.

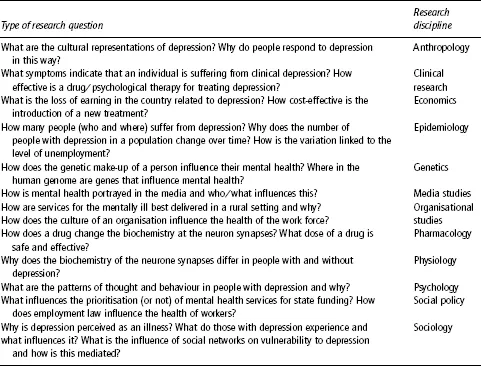

Research from many disciplines directly or indirectly informs the assessment and management of this patient. Different research disciplines tend to tackle different types of research question. Table 1.2 suggests examples of research questions inspired by encountering the man in the example above and the research discipline most likely to tackle each one. Notice the different focus of the different disciplines including: society, community, organisations, individuals, groups of individuals, physiology, biochemistry and genetics. Note also the different types of question words used: what, where, when, how, why, who. We consider the development of research focus and research questions in Chapter 2.

The research questions in Table 1.2 all feed into an overall research question of interest to health professionals:

Why do people get depressed and why do they get better (or not)?

Table 1.2 Examples of the types of research question different academic and research disciplines may ask in relation to depression

It is unlikely that one piece of research could answer this overall question, but we build up understanding of depression through many different research projects undertaken in many different disciplines using various research approaches.

Whatever health problem we research, we need to remain open to the possibility that our research may suggest that health professionals don’t have a lot to offer but that change is needed in the environment or society. For those of us working as health professionals, keeping an open mind about this can be difficult as it seems to undermine ourselves as health professionals and those who experience illness. However, keeping an open mind is vital for research and does not prevent us continuing to recognise the distress experienced by patients. If our research does suggest that what health professionals do makes little difference, this is an important contribution to the ongoing spiral of research activity. Other researchers will pick up the research issue and investigate it in a different way.

Finding out new knowledge while also improving health care

Research is sometimes considered as something very different from activities such as evaluation and audit that aim to improve health care. This can lead to health professionals feeling they can do audit and evaluation but cannot do research. However, there is no clear boundary between these activities and health professionals can contribute to both, often at the same time.

In research we aim to step back from studying particular people in a specific place and timeframe to ask what the study can tell us generally about how the world functions. Audit and evaluation are terms used to describe the process of studying a local health care service with the aim of improving that service. For example, an audit of diabetes care may involve the health professionals providing that care identifying people with diabetes who are not having regular checkups, changing how they provide check-ups with the aim of improving the service, then observing whether those changes have made a difference. Evaluation also looks at the effect of changing how health care is delivered, though this may be undertaken by people not involved in providing the service. The methods of collecting data and analysing it may be similar for audit, evaluation and research. One of the key differences is the audience for the results. Generally, audit is for the practitioners in a local health care service, evaluation is for those making decisions about health care service provision, and research is for a wider audience to contribute to increasing knowledge of health and health care overall. However, studies aimed at a local audience can contribute to the development of new understanding more generally.

| Box 1.1 | Evaluation of waiting times in an emergency department |

The manager of a busy hospital emergency department notices that many people attending seem to wait for hours before a decision is made about whether they stay in hospital or go home. This problem has been the focus of much media attention, so the manager knows it is not just a problem for this hospital. The manager cannot sort out the problem for the whole country, but can find out what is happening in his own department and why.

The manager asked those working in the department what they thought caused the long waits, but they all had different views on the issue. He therefore sought advice from colleagues experienced in the evaluation of organisations and decided to measure the length of time patients waited at different points in their progress through the emergency department. He set up a data collection system tracking where patients wait, how long they wait and what they wait for; for example, the length of wait to speak to the reception clerk, the wait to see a doctor, the wait to go to X-ray. Analysis of these patient flows showed that a major delay was the wait for a porter to take patients to X-ray.

With this evidence that the department needs an extra porter he presented the evaluation to the hospital executive board. They were convinced by the results, as they could follow how the data had been collected and that it revealed what really happens in the emergency department.

As the manager had worked out how to collect the data about patient waits without disrupting the everyday work of the department, he was able to collect data again, after the introduction of the extra porter. The evaluation therefore became an ongoing audit.

There are many different ways in which a local study can contribute to the development of new knowledge. Box 1.1 illustrates this using the example of an evaluation of the waiting times for patients in the emergency department of a hospital. The evaluation showed that the emergency department needed an extra porter. If the project were presented at a national conference about emergency care, people might return to their own departments suggesting an increase in the number of porters. Imagine what might happen: in some places an extra porter might reduce patient waiting times, in others it might make no difference because there were different causes of delay, and in some it might increase the patient waiting times as it led to a reduction in porters elsewhere in the hospital. Although the results of an evaluation may not seem to be of use to other people, there are many ways in which its findings can provide useful new knowledge as discussed below.

If the evaluation were presented in some detail, those hearing about it could assess whether their emergency department was similar to the original department, and from this make a judgement as to whether an extra porter would make a difference in their own department. For those of us working in the UK, where national policy has a strong influence on how local services are delivered, it may be possible to find sufficient similarity to be fairly sure the solution will work so it can be directly transferred to a different department (transferability). Someone from a very different health care service would need to assess this very carefully as fundamental service issues, such as who is responsible for paying for what, can make a big difference to how a service functions. Of course, the only way of being sure is to try it out and assess what happens. If a number of emergency departments tried out introducing extra porters and observed and r...