1

CONTENDING THEORIES OF U.S. BARGAINING WITH ALLIES OF CONVENIENCE

Because allies are governments, each is a more or less complex arena for internal bargaining among the bureaucratic elements and political personalities who collectively comprise its working apparatus. Its action is the product of their interaction. They bargain not at random but according to the processes, conforming to the perquisites, responsive to the pressures of their own political system.

—Richard Neustadt, Alliance Politics

How effectively does the United States bargain with its most treacherous allies, particularly when important national security interests are at stake? Alliance scholars have almost entirely ignored the phenomenon of alliances of convenience, focusing their empirical studies predominantly on America’s formal alliances with friendly democracies and, to a much lesser extent, friendly autocracies. Two prominent bargaining theories, neorealist alliance theory and the two-level games theory of tying hands, propose that, at least since 1945, the United States should have bargained successfully with all of those allies, albeit for different reasons. Neorealism attributes this outcome to the nation’s favorable international systemic position compared to that of its allies of convenience, which were all far less powerful and more immediately endangered by the shared threats that precipitated the formation of the alliances. Tying hands attributes U.S. success to the large disparity in formal decisionmaking power between U.S. leaders and the exclusively autocratic leaders of its allies of convenience. By contrast, I advance a novel theory of alliance bargaining that is drawn from the neoclassical realist research program in International Relations (IR), which makes the opposite prediction. It hypothesizes that heavy domestic opposition to the formation of alliances of convenience should have compelled U.S. leaders to squander America’s advantageous international systemic position by adopting a passive bargaining posture toward those allies, resulting in bargaining failure.

AN INCONVENIENT GAP IN THE ALLIANCE LITERATURE

Over the past several decades, a burgeoning academic literature has sought to explain the origins, management, and effectiveness of military alliances. Several recent contributions have thickened a previously thin canon pertaining to their management or bargaining dimension. Although many, if not most, advance theories and arguments that are applicable to alliances of convenience between the United States and hostile autocracies, their authors have exhibited a strong bias in favor of testing their propositions in U.S. alliances with fellow democracies.

This tendency is evident in five major works on alliance politics published in recent years. In Warring Friends: Alliance Restraint in International Politics (2008), Jeremy Pressman devises a neoclassical realist theory that somewhat resembles the one I propose below to account for the ability and willingness of powerful states to restrain the foreign policy behavior of weaker allies. He tests the four propositions derived from the theory in the two cases of (formal) U.S. alliance relations with Britain during the 1950s and (informal) U.S. alliance relations with Israel between the early 1960s and the early 2000s.1 In America’s Allies and War: Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Iraq (2011), Jason Davidson advances a different neoclassical realist theory to explain variations in the commitments of America’s NATO allies of Britain, France, and Italy to seven U.S.-led military interventions since the end of World War II.2 Stefanie von Hlatky similarly deploys a neoclassical realist theory in American Allies in Time of War: The Great Asymmetry (2013) to account for the unipolar United States’ mixed record in bargaining with Canada, the United Kingdom, and Australia during the Afghanistan and Iraq wars that followed the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks.3 In NATO in Afghanistan: Fighting Together, Fighting Alone (2014), David Auerswald and Stephen Saideman seek to explain the varying proclivity of America’s NATO allies to impose restrictions or caveats on their military activities during the post-9/11 U.S.-led war in Afghanistan.4 In an important recent article in the flagship journal International Security, Gene Gerzhoy tests his argument that under certain conditions a nuclear-armed state can successfully coerce an ally into aborting the pursuit of nuclear weapons by examining U.S. bargaining with its NATO ally West Germany between 1954 and 1969.5

Although some works have focused on U.S. military cooperation with autocratic states, a number of these have been atheoretical. Prime examples are two edited volumes, Friendly Tyrants: An American Dilemma (1991), edited by Daniel Pipes and Adam Garfinkle, and Dealing with Dictators: Dilemmas of U.S. Diplomacy and Intelligence Analysis, 1945–1990 (2006), edited by Ernest May and Philip Zelikow.6 Both books consist of several historical case studies of U.S. alliances with various right-wing anticommunist dictatorships during the Cold War. Their usefulness is limited, however, by their lack of a unifying theoretical framework. In addition, neither book explores the United States’ Cold War alliances with anti-Soviet left-wing dictatorships. This latter critique obviously also applies to David Schmitz’s Thank God They’re on Our Side: The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships, 1921–1965 (1999) and The United States and Right-Wing Dictatorships (2006).7 In this sweeping two-part history, Schmitz broadly contends that the United States established alliances with right-wing anticommunist dictatorships of various stripes from the 1920s through the end of the Cold War because they “promised stability, protected American trade and investments, and aligned … with Washington against the enemies of the United States.”8

Two more theoretically self-conscious contributions to the literature on U.S. alliances with autocracies are Douglas MacDonald’s Adventures in Chaos: American Intervention for Reform in the Third World (1992) and Victor Cha’s Powerplay: The Origins of the American Alliance System in Asia (2016).9 MacDonald argues that U.S. efforts to induce right-wing authoritarian allies to implement domestic reforms during the Cold War were constrained, primarily by the intensity of Washington’s commitment to those states’ security. Cha contends that the United States negotiated formal bilateral alliances in East Asia after World War II in order to maximize its leverage and control over much weaker but potentially troublesome small-power partners. However, none of the alliances studied by MacDonald (Nationalist China, 1946–1948; the Philippines, 1950–1953; and South Vietnam, 1961–1963) or Cha (South Korea and Taiwan in the early 1950s) meet my criteria for categorization as alliances of convenience. According to my typology, the U.S. allies surveyed in these two books fall under the more benign category of ambivalent allies, which had autocratic political systems but possessed geopolitical interests that were closely aligned with those of the United States.10 In addition, MacDonald’s argument explains U.S. efforts to modify its authoritarian allies’ domestic politics, whereas the present study focuses on attempts by the United States to modify the behavior of its allies on salient national security–related issues.

Only two relatively recent theoretical works on U.S. alliance management—Alexander Cooley’s Base Politics: Democratic Change and the U.S. Military Overseas (2008) and Tongfi Kim’s The Supply Side of Security: A Market Theory of Military Alliances (2016)—include brief discussions of allies of convenience.11 Cooley is not interested in alliance politics broadly defined, but rather in the conditions under which U.S. military bases in foreign states are accepted domestically in those states. He argues that the host country’s response to U.S. basing hinges on the degree to which the host regime is politically dependent on the security contract with Washington and the contractual credibility of the host state’s political institutions. One of several cases that Cooley examines, which I classify as an alliance of convenience, is the basing agreement signed by the United States in 1953 with General Francisco Franco’s Spain (Treaty of Madrid). Although Cooley touches on some of the compromises made by both sides in negotiating and later renegotiating the treaty, he is primarily interested in showing both that it brought legitimacy (and American economic assistance) to the Franco regime and that this legitimacy was weakened following Franco’s death and the advent of democratic rule in Madrid.12 Kim examines the trajectory of the U.S. alliance with Spain from the Treaty of Madrid through 2004. In accordance with Kim’s market theory of alliances, which proposes that an ally will have to make fewer concessions to a pro-alliance leader in the partner state whose hold on power is secure, he claims that Washington had to make few concessions to Franco in order to maintain the alliance.13

In sum, IR scholars have not yet subjected alliances of convenience and U.S. relations with such allies to rigorous scrutiny. Since the United States has frequently partnered with allies of convenience to thwart impending threats, only to subsequently wage hot and cold wars against them, it is imperative that scholars and policymakers achieve a more refined understanding of the dynamics attendant to these uniquely complex and challenging bilateral relationships.

RIVAL THEORIES OF ALLIANCE BARGAINING

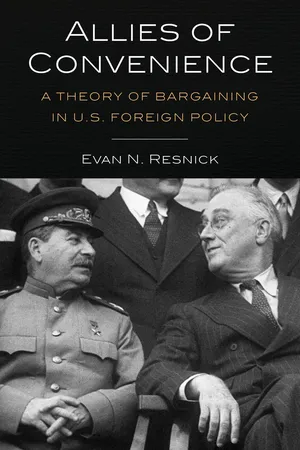

This book restricts the temporal scope of study to the period 1945–2015. Prior to 1945 the relative power of the United States vis-à-vis its allies of convenience varied widely over time from relative weakness to relative parity, complicating the analysis. At the time of its first such alliance, struck with Louis XVI’s France during the American Revolutionary War, the thirteen rebelling colonies together constituted a minor actor in the great power system centered in Europe. By the time of its final pre-1945 alliance of convenience with Stalin’s Soviet Union during World War II, the United States had risen to become one of several great powers—along with the USSR—in a multipolar international system. Since 1945, however, it has been one of two superpowers in a bipolar Cold War system and subsequently the sole great power in a post–Cold War unipolar system, while all of its allies have been small powers. This configuration seems more likely to resemble U.S. alliances in the near-term future than does the pre-1945 model. Although the gap in power and wealth between the United States and “the rest” has shrunk in recent years, a considerable body of evidence indicates that it should remain predominant for several years to come. Even if the upward trajectory of China’s relative rise in power is steeper than these data predict, the international system will resemble the tw...