![]()

1

Quality, Quantity and Knowledge Interests: Avoiding Confusions

Martin W. Bauer, George Gaskell and Nicholas C. Allum

KEYWORDS

data analysis

data elicitation

the ideal research situation

knowledge interests

the law of instrument

mode and medium of representation

research design

Imagine a football match. Two opposing players run after the ball, and suddenly one of them falls to the ground, rolling over several times. Half the spectators whistle and shout, and the other half are relieved that the potential danger is over.

We may analyse this competitive social situation in the following terms. First, there are the actors: the football players, 11 on each side, highly trained, skilled and coordinated in their roles for the purpose of winning the match; and the officials, namely the referee and the linesmen. This is the ‘field of action’.

Then we have the spectators. Most of the spectators are loyal supporters of one or other of the teams. Very few do not identify with either of the teams. However, there may be one or two spectators who are new to football, and are just curious. The terraces of the spectators are the ‘field of naive observation’ – naive in the sense that the spectators are basically enjoying events on the pitch, and are almost a part of the game itself, which they may experience almost as if they were players. Through their loyalty to one of the teams, they think and feel with a partisan perspective. When one of the players falls, this is interpreted by his supporters as indicating foul play, while for the opposing fans it is a self-inflicted and theatrical stumble.

Finally, there is the position from which we describe the situation as we do here. We are curious about the tribal nature of the event, of the field of action, and of the spectators under observation. Ideally this description requires a detached analysis of the situation, with no direct involvement with either team. Our indirect involvement may be in football in generalits present problems and its future. This we call the ‘field of systematic observation’. From this position, we may be able to assemble three forms of evidence: what is going on on the field, the reactions of the spectators, and the institution of football as a branch of sport, show business or commerce. Avoiding direct involvement requires precautions: (a) a trained awareness of the consequences that arise from personal involvement; and (b) a commitment to assessing one’s observations methodically and in public.

Such observations with different degrees of detachment are the problematic of social research. By analogy we can readily extend this ‘ideal type’ analysis of what we call a ‘complete research situation’ (Cranach et al., 1982: 50) to other social activities, such as voting, working, shopping and making music, to mention just a few. We can study the field of action, and ask what the events are in the field (the object of study); we may subjectively experience each event – what is happening, how it feels, and what are the motives for it. This naive observation is analogous to the perspective of the actors as self-observers. Finally, we focus on the subject – object relation that arises from the comparison of the actor perspective and the observer perspective within a larger context, and ask how events relate to people’s experience of them.

Adequate coverage of social events requires a multitude of methods and data: methodological pluralism arises as a methodological necessity. Recording the action field requires (a) the systematic observation of events; inferring the meanings of these events from the (self-) observations of the actors and spectators requires (b) techniques of interviewing; and interpreting the material traces that are left behind by the actors and the spectators requires (c) systematic analysis.

Research design: data elicitation, reduction and analysis

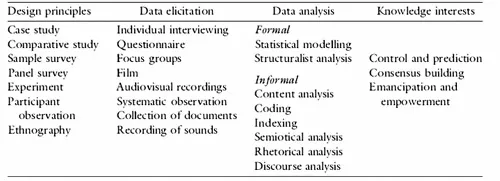

It is useful to distinguish four methodological dimensions in social research. These dimensions describe the research process in terms of combinations of elements across all four dimensions. First, there is the research design according to the strategic principles of research, such as the sample survey, participant observation, case studies, experiments and quasi-experiments. Secondly, there are the data elicitation methods, such as interviewing, observation and the collection of documents. Thirdly, there are the data analytic procedures, such as content analysis, rhetorical analysis, discourse analysis and statistics. And finally, knowledge interests refer to Habermas’s classification into control, consensus building and emancipation of the subjects of study. The four dimensions are elaborated in Table 1.1.

Much methodological confusion and many false claims arise from the confounding of the qualitative/quantitative distinction of data eliciting and analysis with principles of research design and knowledge interests. It is quite possible to conceive an experimental design accommodating in-depth interviewing to elicit data. Equally, a case-study design may incorporate a survey questionnaire together with observational techniques, for example to study a business corporation in trouble. A large-scale survey of an ethnic minority group may include open questions for qualitative analysis, and the results may serve the emancipatory interests of the minority group. Or we can think of a random survey of a population, collecting data through focus group interviews. However, as the last example shows, certain combinations of design principles and data eliciting methods occur less frequently because of their resource implications. We contend that all four dimensions should be viewed as relatively independent choices in the research process, and the choice of qualitative or quantitative is primarily a decision of data eliciting and analysis methods, and only secondarily one of research design or knowledge interests.

Table 1.1 The four dimensions of the research process

While our examples have included survey research, in this volume we deal mainly with data eliciting and analysis procedures within the practice of qualitative research, that is, non-numerical research.

Modes and mediums of representation: types of data

Two distinctions about data may be helpful in this book. The world as we know and experience it, that is, the represented world and not the world in itself, is constituted in communication processes (Berger and Luckmann, 1979; Luckmann, 1995). Social research therefore rests on social data – data about the social world – which are the outcome of, and are realized in, communication processes.

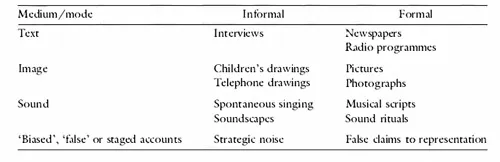

In this book we distinguish two modes of social data: informal and formal communication. Furthermore, we distinguish three media out of which data can be constructed: text, image and sound materials (see Table 1.2). Informal communication has few explicit rules: people can talk, draw or sing in any way they like. That there are few explicit rules does not mean that rules do not exist, and it may be that the very focus of social research is to uncover the hidden order of the informal world of everyday life (see Myers, Chapter 11 in this volume, on conversation analysis). In social research we are interested in how people spontaneously express themselves and talk about what is important to them, and how they think about their actions and those of others. Informal data are constructed less according to the rules of competence such as govern text writing, painting or musical composition, and more on the spur of the moment, or under the influence of the researcher. The problem arises that the interviewees tell what they think the researcher would like to hear. We need to recognize false accounts, which may say more about the researcher and the research process than about the researched.

Table 1.2 Modes and media

On the other hand, there are acts of communication that are highly formal in the sense that competence requires specialist knowledge. People need to be trained to write articles for a newspaper, to generate pictures for an advertisement, or to produce an arrangement for a brass band or a symphony orchestra. A competent person has mastered the rules of the trade, sometimes in order to break them productively, which is called innovation. Formal communication follows the rules of the trade. The fact that the researcher uses the resulting traces, such as a newspaper article, for social research is unlikely to influence the act of communication: it makes no difference to what the journalist wrote. In this sense data based on traces are unobtrusive. However, a second-order problem arises in that the communicators may claim to represent a social group that, in reality, they do not represent. The social scientist must recognize these false claims of representation.

Formal data reconstruct the ways in which social reality is represented by a social group. A newspaper represents the world for a group of people in an accepted way, otherwise people would not buy it. In this context the newspaper becomes an indicator of their worldview. The same may be true for pictures that people consider interesting and desirable, or music that is appreciated as beautiful. What a person reads, looks at, or listens to places them in a certain category, and may indicate what the person may do in the future. Categorizing the present and at times predicting future trajectories is the quest of all social research. In this book we focus almost exclusively on the former issue: the categorization problem.

The philosophy of this book assumes that there is no ‘one best way’ of doing social research: there is no good reason for us all to become ‘pollsters’ (people who conduct opinion polls), nor should we all become ‘focusers’ (people who conduct focus groups). The purpose of this book is to overcome the ‘law of instrument’ (Duncker, 1935), according to which a little boy who only knows a hammer considers that everything is in need of a pounding. By analogy, neither the survey questionnaire nor the focus group is the royal road for social research. This route can, however, be found through an adequate awareness of different methods, an appreciation of their strengths and weaknesses, and an understanding of their use for different social situations, types of data and research problems.

We have now established that social reality can be represented in informal or formal ways of communicating, and that the medium of communication can be texts, images or sound materials. In social research we may want to consider all of these as relevant in some way or another. This is what we hope to clarify.

Qualitative versus quantitative research

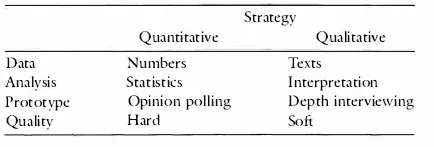

There has been a lot of discussion about the differences between quantitative and qualitative research. Quantitative research deals with numbers, uses statistical models to explain the data, and is considered ‘hard’ research. The best-known prototype is opinion-poll research. By contrast, qualitative research avoids numbers, deals with ‘interpreting’ social realities, and is considered ‘soft’ research. The best-known prototype is probably the depth interview. These differences are displayed in Table 1.3. Much effort has been invested in juxtaposing quantitative and qualitative research as competing paradigms of social research, to the extent that people have built careers in one or the other, often polemicizing on the superiority of hard over soft or soft over hard research. Publishers have been quick to spot a market and have established book series and journals with the effect of perpetuating this distinction.

It is fair to say that much quantitative social research is centred around the social survey and the questionnaire, supported by SPSS and SAS as standard statistical software packages. This has set the standards of methodological training at universities, so that the term ‘methodology’ has come to mean ‘statistics’ in many fields of social science. In parallel, a large business sector has developed, offering quantitative social research for a multitude of purposes. But recent enthusiasm for qualitative research has successfully challenged the simple equation of social research and quantitative methodology; and a space has reopened for a less dogmatic view of methodological matters – an attitude that was common among the pioneers of social research (see, for example, Lazarsfeld, 1968).

Table 1.3 Differences between quantitative and qualitative research

In our own efforts, both in research and in teaching social research methods, we are trying to find a way of bridging the fruitless polemic between two seemingly competing traditions of social research. We pursue this objective on the basis of a number of assumptions, which are as follows.

No quantification without qualification

The measurement of social facts hinges on categorizing the social world. Social activities need to be distinguished before any frequency or percentage can be attributed to any distinction. One needs to have a notion of qualitative distinctions between social categories before one can measure how many people belong to one or the other category. If one wants to know the colour distribution in a field of flowers, one first needs to establish the set of colours that are in the field; then one can start counting the flowers of a particular colour. The same is true for social facts.

No statistical analysis without interpretation

We think it odd to assume that qualitative research has a monopoly on interpretation, with the parallel assumption that quantitative research reaches its conclusions quasi-automatically. We ourselves have not conducted any numerical research without facing problems of interpretation. The data do not speak for themselves, even if they are highly processed with sophisticated statistical models. In fact, the more complex the model, the more difficult is the interpretation of the results. Claiming the ‘herme-neutic circle’ of interpretation, according to which better understanding comes from knowing more about the field of research, is for qualitative researchers a rhetorical move, but one that is rather specious. What the discussion on qualitative research has achieved is to demystify statistical sophistication as the sole route to significant results. The prestige attached to numerical data has such persuasive power that in some contexts poor data quality is masked, and compensated for, by numerical sophistication. However, statistics as a rhetorical device does get around the problem of ‘garbage in, garbage out’. In our view, it is the great achievement of the discussion on qualitative methods that it has refocused attention in research and training away from analysis and towards the issues of data quality and data collection.

It seems that the distinction between numerical and non-numerical research is often confused with another distinction, namely that between formalization and non-formalization of research (see Table 1.4). The polemic around these types of research is often conflated with the problem of formalism, and based on the methodological socialization of the researcher. Formalism involves abstractions from the concrete context of research, thus introducing a distance between the observation and the data. In a sense, formalism is a general-purpose abstraction available for treating many kinds of data providing certain conditions are satisfied, such as independence of measures, equal variance and so on. The abstract nature of formalism involves such specialization that it can lead to a total disinterest in the social reality represented by the data. It is often this ‘emotional detachment’ that is resented by researchers of other persuasio...