![]()

Part One

The Peredvizhniki Represent Themselves

![]()

1

Commercial Institutionalization, 1870–71

Be as cunning as serpents and as innocent as doves.

Grigorii Miasoedov quoting Matthew 10.16

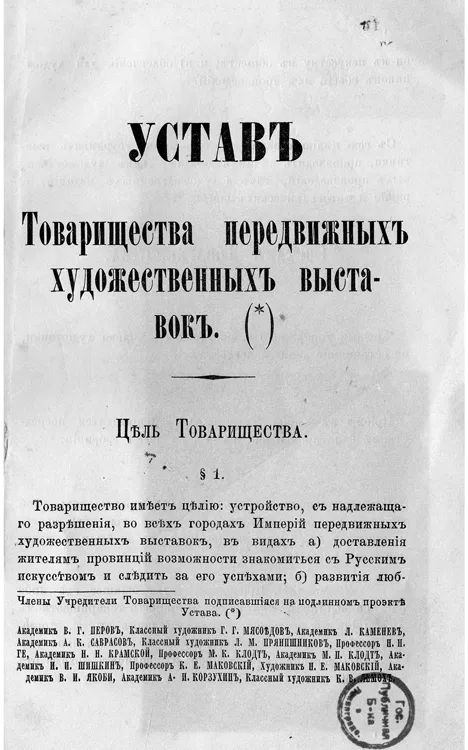

The Peredvizhniki’s foundation was anything but a spontaneous and unmistakably aesthetic decision. In the first – and for a long time the only – public document which declared the aims and methods of the newly founded group, the artists made it clear that they were creating a commercial exhibition enterprise. On 23 November 1870, an official charter registered the group under the compound name Tovarishchestvo peredvizhnykh khudozhestvennykh vystavok or the Partnership for touring art exhibitions (Figure 1; see also Appendix 1). The first paragraph of the charter stated that the Partnership had been formed with the aim of organizing regular commercial touring exhibitions of Russian art. The following paragraphs describe the organizational and economic mechanisms for achieving this aim. In particular, from the ‘Membership’ section it can be inferred that the Partnership was to be open to all practising artists, who could join it to exhibit and sell their works independently and directly. The management of the Partnership was to be shared between two bodies: the annual General Meeting of all members and the Executive Board, whose members were to be appointed annually and who would undertake the day-to-day administration of each touring exhibition. The section entitled ‘Funds’ implies that the Partnership planned to finance the touring exhibitions through the sale of tickets and publications and through a 5 per cent commission from works sold; this commission would, nevertheless, remain the property of the individual artists, comprising their share in the Partnership Fund. This section also explains the two major sources of income for the members: the sale of their individual works, and dividends from the annual net profit of the exhibitions. Finally, we also learn from this section that the Partnership was to hire a special person to accompany the provincial part of the tour – that is, right from the start it was an exhibition, not a group of artists, that was intended to travel. In short, in the charter the artists set out in considerable detail the organizational aspects and anticipated economic benefits from the new exhibition enterprise. The only specific evidence as to a possible artistic motive behind the launching of the Partnership is provided by the words ‘Russian art’ in the description of the type of exhibitions the artists were intending to organize. This description, however, seems to be all-purpose and aesthetically open in the entirely business context of the charter. And the fact that the founding members mention their official professional titles and designations, bestowed by the Imperial Academy of Arts’ ranking system, only served to reinforce the impression of legitimacy.1 Among the fifteen artists who signed the charter were three professors (the highest title): Nikolai Ge (St Petersburg), Mikhail K. Klodt (St Petersburg) and Konstantin E. Makovskii (St Petersburg); eight academicians: Vasilii Perov (Moscow), Lev Kamenev (Moscow), Aleksei Savrasov (Moscow), Ivan Kramskoi (St Petersburg), Mikhail P. Klodt (St Petersburg), Ivan Shishkin (St Petersburg), Aleksei Korzukhin (St Petersburg) and Valerii Iakobi (St Petersburg); three ‘Master artists’: Karl Lemokh (St Petersburg), Grigorii Miasoedov (Moscow) and Illarion Prianishnikov (Moscow); and one ‘Artist’: Nikolai E. Makovskii (St Petersburg).2 At the first General Meeting on 16 December 1870, this group of largely established artists gave itself another year to prepare for the inaugural exhibition.

Figure 1 The title page of the Partnership Charter registered in 1870.

Employing dry, precise and bureaucratic language, the charter was apparently all the artists openly said or wished to say about themselves in the beginning. Why is it that the Peredvizhniki proffered themselves as a commercial and aesthetically open undertaking, at the expense of any reference to their interest in promoting a specific artistic agenda (e.g. realism) which conventional art history would have us believe was their motivation?

To understand the artists’ behaviour and self-presentation, one first needs to realize that the new group, while taking advantage of a growing social mobility in the country, had to register its existence with the Ministry of the Interior, and thus had to act within the constraints imposed by the contradictory political culture of the time.

On the one hand, the Partnership emerged and took shape at a particularly opportune historical moment – only a decade after Alexander II’s major liberal reforms had modernized Russia’s social structure, stimulating mobility. In simple terms, one of the major after-effects of the reforms was the transformation of an estate (soslovnoe) society (judicially fixed nobility, clergy, urban residents and rural inhabitants) into a class society, the most distinguishing marks of which were and still are occupation, income and social capital. It was a shift towards a modern society where ‘the facts of education and individual initiative played a larger role in determining one’s prospects’.3 Historians agree that most reformers of the 1860s aspired to a transition from paternalistic control to the development of private and associative initiatives. As Gregory Freeze has remarked: ‘Aware that the state lacked the capability or even financial means to modernize, the reformers endeavoured to liberate society’s own vital forces and to create structures […] where local initiative could sponsor development.’4 This shift also had a direct effect on the arts: it was at this time that the ideology of ‘mutual assistance’ among art professionals and art lovers attracted a large following, which resulted in the formation of several of the societies and enterprises to be described here.

On the other hand, Joseph Bradley argues that ‘the legal status and political environment of Russian associations were precarious and to a great degree determined by an autocratic state’. As they were voluntary, any such professional associations – whether in science or, as in our case, in the arts – demonstrated the potential for the self-organization of society. For their normal activities included public speaking, the compiling and publicizing of reports, conducting meetings and the electing and rotating of its governing bodies, all of which exposed association members to ‘constitutional structures and parliamentary procedures’. Such private collective initiatives in a public space inevitably constituted a critical element in the effort to gradually emancipate society from the arbitrary rule of autocracy.5 In consequence, the Russian government’s overall regulating policy, as defined by the authoritarian state, remained the same. According to the law, which was emphasized and clarified in 1867, it was ‘forbidden to all and everyone to organize and introduce a society, partnership, brotherhood or any such gathering of people in a city without informing or receiving the approval of the government’.6 Even if the artists had no direct knowledge of this unambiguous article of the Charter on Anticipation and Prevention of Crime, the state’s attitudes to organized associations would have been wholly familiar to them. In registering a new society, therefore, the artists had to formulate a charter which specified the aims and means of the organization while simultaneously respecting the conditions imposed by the state. But this was not the only overlap between the fields of power and art.7 All printed materials were subject to censorship. With very few exceptions, ‘any work of print, when printed, before its public dissemination’ had to be submitted to the local censor, according to the Charter on Censorship and Print. Among the exceptions were exhibition advertisements, the approval ‘of any posters and small announcements’ being ‘delegated to local police authorities’ instead. Those aspects of the censorship rules that would have had a direct effect on the publishing activity of the Peredvizhniki remained the same throughout the entire period in question.8 The phrase ‘approved by the censor’ was applied to – and can be observed on – all printed materials, from the charter, to the catalogues and public reports of the Partnership. While their awareness of censorship does not entirely explain the artists’ reticence, it may offer a first insight into their approach: to provide only what was expected by the terms of registration.

The three surviving private letters of the artists reveal more of the earliest thinking behind the foundation of the Partnership within such an uneasy socio-political context. The first letter contains an outline of a charter along with a commentary. It was sent in November 1869 by six Moscow artists, including Miasoedov and Vasilii Perov, to the St Petersburg Artel of Artists, a form of artists’ cooperative. The second and third letters are from Miasoedov to Ivan Kramskoi – two leaders of the project in Moscow and St Petersburg respectively. The second letter, from February 1870, sets out some of the doubts and expectations of the artists, while the third, from September 1870, implies that the artists might use some of their personal contacts in the government to move the registration of the new organization forward. The fact that the registered version of the charter does not differ significantly from the draft version suggests that the artists spent the entire year discussing not so much its content as the possible consequences of its registration. Evidence for this can be found in the first two letters, which primarily concentrate on two issues: the necessity for a private and commercially independent exhibition enterprise – the first of its kind – and the political or, more precisely, the professional risks entailed in realizing such an initiative.9

The initiative of the ‘privatization’ of exhibition practice in an authoritarian country could be easily politicized, and the surviving correspondence demonstrates that Petersburg and Moscow artists were apparently divided over the evaluation of that kind of risk. Specifically, the Moscow-based artists felt enthusiastic about the new project, while it was those from the St Petersburg Artel who were rather apprehensive about any new undertaking.10 The Muscovite Miasoedov argued in the letter to Kramskoi in February 1870: ‘It is probably because we are ground down and full of timidity that the business seems more threatening than it actually is.’11 The artists of the two cities obviously shared common knowledge of recent developments in the field of art but clearly had different first-hand experiences. Seven years earlier, a controversial event had taken place in St Petersburg – the so-called Revolt of the Fourteen, led by Kramskoi – which evidently still traumatized some of the Petersburg painters, while being a source of rather pragmatic inspiration for their Moscow counterparts. Briefly, on 9 November 1863 fourteen students from the St Petersburg Academy had refused to participate in the Gold Medal competition because their request to be allowed to select their own subject had been ignored. The contestants withdrew from the Academy.12 It is almost certain that there was a ban on supporting the ‘revolt’ in the press, while police agents were instructed ‘to watch covertly the acts of these young men and the direction of the society they have launched [the St Petersburg Artel of Artists]’.13 The government, however, eventually legalized this enterprise comprising the former dissenters, perhaps because the protesters clearly wanted to avoid any politicization of their action.14 (Elizabeth Valkenier has argued with some justification that, unlike their contemporaries at the University of St Petersburg, students at the Academy of Arts were politically rather inexperienced and unengaged, due to their inferior education and social standing.15) The Moscow artists appear to have derived a positive lesson from this story. In the same letter, Miasoedov continued, expounding the benefits brought about by the ‘revolt’: ‘why would you, who protested so sharply, and had practical knowledge that your protest would not lead to anything bad (you are now decorated with titles, and supplied with commissions), not encourage the shy ones’ to take part in the Partnership. Ultimately, the arguments of the Muscovites won out, though Kramskoi and Karl Lemokh were the only former Artel members to join the new Partnership. In short, the recent historical developments in the art world apparently reinforced the sense of the Moscow artists that the risks in questioning the existing official monopoly on exhibitions were not too great, provided the artists do everything ‘according to the law’ and ‘without any fuss, but energetically’; with ‘no compromises and without beating a drum’ – in other words, to ‘be as cunning as serpents and as innocent as doves’.16 The founding members clearly wished to avoid any questions and complications during the process of government registration, and therefore their charter merely followed the generic requirements of an official government document.

Further evidence suggests, however, that such a pra...