![]()

CHAPTER 1

Do You Want to Drive the Bus?

Leaders Often Underestimate Leadership

200 Souls

The year was 1945. My grandfather, together with millions like him, returned home from the war to a bleak welcome. His family’s house in South East London had been extensively damaged in the war. My father and aunt (then just children) and my grandmother were in dire need of warmth, nourishment, and a roof over their heads. The arrangement in those days was that everyone returning from the front had the right to take up the job that he or she had held before the war, but unfortunately, my grandfather’s former employer no longer existed. It had been razed to the ground during the Blitz. Without the safety net of a social welfare system (such support was years off), my grandfather’s position was precarious, and it was obvious: his family’s mere survival depended upon him finding employment–and fast.

He applied, it is said, for hundreds of jobs. It was not that he was not employable. He had skills, experience, and no end of drive, but he was not alone. There were literally hundreds of thousands like him searching for and applying for the same positions. In such a saturated market, standing out from the crowd can prove very difficult. Nevertheless, eventually, he returned home one day with the news that he had been offered a job. My grandmother, whom I sadly only had the pleasure to know briefly while I was a small child, was apparently a woman of few words. Family lore says that she was only known to show her emotions on a couple of occasions in her life. The day my grandfather came home with the job offer was one of those times.

My grandmother danced around the front room with the children, smiling across her face as she sang, We’re saved … everything is going to be alright … Daddy has a job…. However, my grandfather did not have a job. He had indeed been offered a position to work as a London bus driver, but he had turned down the offer. He had not taken the job.

Apparently, that was the second time in her life that my grandmother showed her emotions.

With sheer consternation, she harangued my grandfather for what she viewed as an awful decision. How could he turn down such a job offer, such a gift? How could he put his family’s welfare on the line with such a decision? She pleaded. My grandfather, whom I never met as he sadly died before I was born, solemnly responded to his wife’s vociferous appeals:

Darling, I turned down the job, because I did not want the responsibility of 200 souls on my bus.

After much consideration, I, personally have come to the firm conclusion that I am hugely impressed by my grandfather’s decision. He had the strength of conviction to make such a difficult decision despite acute awareness of the potential ramifications for others (his family). He put his values before potential material gain when he decided that he did not want to bear such a large responsibility. Some may see such a move as cowardly or feeble, but not I. For me, he had reflected on and made the most important and wide-ranging decision a professional can make, namely:

Do I want to take on the responsibility?

Leaders bear the burden of responsibility, irrespective of industry. In my nearly two decades as a management consultant and coach, I have unfortunately heard regret expressed by hundreds of leaders, from many different industries.

Sometimes, I wish I had never become a manager! This is not what I had thought it would be like…I am not cut out for this…I wish I had more time for my family…I take these issues home with me…it consumes me…being a leader has made me ill. Et cetera.

My message here is not that leadership and management are solely bad stars to follow and should not be recommended as career paths. On the contrary, leadership can be powerful, exciting, stimulating, and hugely rewarding. Leaders have the chance to make a difference.

The message here is that leadership is not for everyone.

Maybe you are just embarking on your professional career, maybe you are looking forward to imminent promotion to your first leadership role, or maybe you are already in such a role. Wherever you currently find yourself on your professional or leadership journey, I implore you to seriously self-reflect and ask yourself whether you truly want the responsibility and all the trappings and challenges that come with leadership. Before you read the rest of this book, you should be able to honestly answer the question:

Do I want to drive the bus?

Would You Push the Big Guy?

There is an exercise that psychology professors sometimes run with their first semester undergrads:

Imagine you are casually going for a walk, minding your own business when you hear the sound of a train in the distance. You turn, and from your position, you can see the train fast approaching. Suddenly, your attention is piqued by a group of youths (seven or eight of them) playing on and near the track (Figure 1.1). They appear to be oblivious to the approaching locomotive. You call out to them to move, but they cannot hear you. Just as you are calculating whether or not you will have the time to run to them to warn them yourself (you will not), you notice that you are standing next to the controls that switch the points. If you were to switch the points, the train would follow the side track and the youths would be saved.

Figure 1.1 Would you switch the points?

In a freakishly similar situation, you find yourself, days later, by another train track. You again witness 7 to 8 people dangerously on or by the rain track (Figure 1.2). A train is fast approaching and will surely kill them all. They cannot hear you. You cannot make it to them fast enough. But, you can switch the points. However, there is a young child on the side track, on the track that you would divert the train to, if you switched the points. You cannot warn or reach either the lone girl or the group of youths. What will you do?

Figure 1.2 Would you switch the points?

Days later (you seem to be having some bad luck on your walks in the country), you find yourself in the same situation again (Figure 1.3). The same as before, but in this case, the single person on the side track is someone very dear to you (for example your mother, partner, or sibling).

Figure 1.3 Would you switch the points?

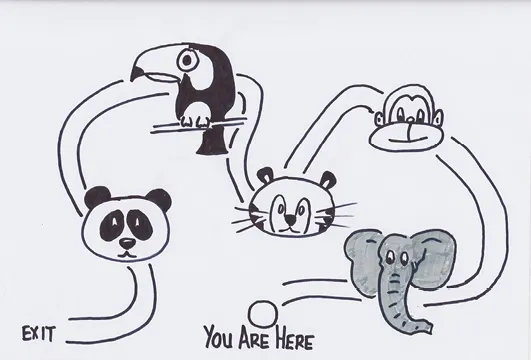

Several days later (déjà vu?) you have decided to change your route through the woods, and instead wander along the top of the hill, overlooking the train track (Figure 1.4). Tragically, you witness a similar situation: a group of people is playing on the track, but this time, you cannot reach the controls to the points in time. You cannot verbally or physically warn the kids that the train is coming. Their fate appears doomed. However, near you, you see a huge man. He must be nearly seven-feet tall and weigh several hundred pounds. He is a powerhouse of a man. Strong, ripped, massive. You quickly surmise that, if you were to push the man from his vantage point on the hill, he would fall in front of the train causing the driver to brake or his large body would slow the speed of the train enough to save the loitering teenagers.

Figure 1.4 Zoo map: you are here

Would you push the big guy?

Admittedly, the preceding situations are extreme. Let us hope neither you nor I nor anyone we know is faced with such intense dilemmas. But, the truth remains that, were we to find ourselves in such high-pressure scenarios, we would have to make a decision. One way or the other.

Reacting to the previous scenarios, almost all subjects asked, choose to switch the points to divert the train to the side track in the first example. When asked, most respond that they would intervene if they felt that their actions could benefit the group. Only a small percentage of respondents say that they would do nothing at all. Indeed, I have also run the example with numerous groups myself, and one or two over the years have answered thus: It was their stupid decision to sit near a train track, so why should I get involved in their lives.

But, the vast majority chose to switch the points. When faced with the second of the dilemmas (1.2.2), the majority, also here, claim that they would switch the points. The most common defense of their actions sounds something like this:

If I were forced to make such a decision, I would choose to save the many over saving the one. Seven lives are more valuable than one.

Interestingly, the water is muddied considerably when people are asked how they would act in situation 1.2.3. The mos...