- 280 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

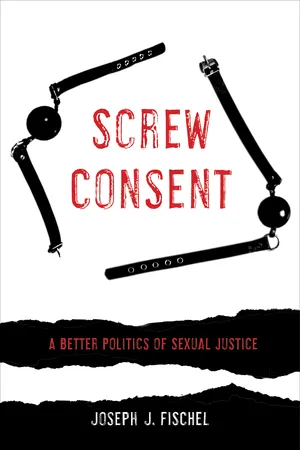

About this book

When we talk about sex—whether great, good, bad, or unlawful—we often turn to consent as both our erotic and moral savior. We ask questions like, What counts as sexual consent? How do we teach consent to impressionable youth, potential predators, and victims? How can we make consent sexy?

What if these are all the wrong questions? What if our preoccupation with consent is hindering a safer and better sexual culture? By foregrounding sex on the social margins (bestial, necrophilic, cannibalistic, and other atypical practices), Screw Consent shows how a sexual politics focused on consent can often obscure, rather than clarify, what is wrong about wrongful sex.

Joseph J. Fischel argues that the consent paradigm, while necessary for effective sexual assault law, diminishes and perverts our ideas about desire, pleasure, and injury. In addition to the criticisms against consent leveled by feminist theorists of earlier generations, Fischel elevates three more: consent is insufficient, inapposite, and riddled with scope contradictions for regulating and imagining sex. Fischel proposes instead that sexual justice turns more productively on concepts of sexual autonomy and access. Clever, witty, and adeptly researched, Screw Consent promises to change how we understand consent, sexuality, and law in the United States today.

What if these are all the wrong questions? What if our preoccupation with consent is hindering a safer and better sexual culture? By foregrounding sex on the social margins (bestial, necrophilic, cannibalistic, and other atypical practices), Screw Consent shows how a sexual politics focused on consent can often obscure, rather than clarify, what is wrong about wrongful sex.

Joseph J. Fischel argues that the consent paradigm, while necessary for effective sexual assault law, diminishes and perverts our ideas about desire, pleasure, and injury. In addition to the criticisms against consent leveled by feminist theorists of earlier generations, Fischel elevates three more: consent is insufficient, inapposite, and riddled with scope contradictions for regulating and imagining sex. Fischel proposes instead that sexual justice turns more productively on concepts of sexual autonomy and access. Clever, witty, and adeptly researched, Screw Consent promises to change how we understand consent, sexuality, and law in the United States today.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

CHAPTER 1

Kink and Cannibals

or Why We Should Probably Ban American Football

Fetishists fetishize consent. Practitioners and sympathetic scholars routinely defend and celebrate kinky sex—BDSM1—for the moral primacy it places upon consent. Certainly BDSM is praised for other reasons too—for eroticizing otherwise flaccid publics, for contravening stale norms of “harmonic” intimacy, for helping practitioners work through earlier traumatic experiences, and for theatricalizing and thereby subverting hierarchical social relations (e.g., Bauer 2014, 3; Califia 1994 [1980], 172–74; Henkin 2007). But nearly all advocacy for BDSM starts with consent as moral square one. Whether conceptualized as a “contract,” a “safe word,” or something far more communicatively cumbersome, consent not only exonerates but also extols BDSM sex. This is consent unbound.

It is time to tie it up.

As the first of two chapters describing the insufficiency of consent for adjudicating sex, this one makes the following five arguments: (1) consent should not green-light any sexual conduct whatsoever simply because the conduct is sexual; (2) while BDSM defenders analogize kinky sex to physical contact sports in support of the former’s legitimacy, the (dis)analogy in fact makes a stronger case for the illegitimacy of the latter, especially American football; (3) (yet) in sex, as in football, the sufficiency threshold for consent should not be, ipso facto, either the seriousness of any given physical injury or an affront to human dignity, as some critics propose; (4) we can begin to excavate alternative sufficiency thresholds to seriousness and dignity by turning to two contradictions within consent-centric, pro-BDSM literature; (5) these contradictions are resolved once consent is checked and once other abstractions—already articulated within the BDSM lexicon—are entrusted with more power. Not incidentally, these other abstractions—mutuality, communication, care for others, power exchange, and so on—sound with a feminist commitment of sexual autonomy and a feminist reconstruction of sexual access.

CHEWING PENIS

On March 9, 2001, two German men in their forties, Armin Meiwes and Bernd Brandes, together attempted to dine on Brandes’s fried penis. Meiwes and Brandes had met online earlier that month, after Meiwes had posted an advertisement soliciting men who wished to be eaten, to which Brandes eagerly responded. Brandes traveled by train to Meiwes’s farmhouse, whereupon the two men had sex before Brandes consumed copious quantities of alcohol and sleeping pills, apparently in anticipation of the ensuing pain of having his penis removed. Meiwes cut off Brandes’s penis after he failed to bite it off, frying the penis when it proved too tough to eat raw. Now charred and inedible, Meiwes fed what was left of Brandes’s member to the dog. Brandes spent the next several hours in a warm bath bleeding out before Meiwes stabbed and killed him with a kitchen knife. Meiwes cut Brandes into pieces, stored some of the remains in the freezer, and buried the skull and bones of the deceased in his backyard. In the months following, Meiwes would periodically dine on Brandes flesh with his “best cutlery” and a glass of red wine (Harding 2003).

Scandalizing this scandal further, Meiwes “had recorded every bloody detail of the slaying on video,” a video in which Brandes evidently and continually consents to his dismemberment and death (although there is some question about the validity of consent given Brandes’s blood loss and intoxication) (Barcroft TV 2016). Following a tip-off, police went to Meiwes’s farmhouse and discovered the frozen flesh and bones of Brandes, as well as the video.

In a German criminal court, Meiwes was convicted of manslaughter, not murder; Brandes’s voluntariness—his consent—in part mitigated Meiwes’s culpability (Harding 2004). However, on appeal Meiwes was convicted of murder and sentenced to prison for life. The court held that consent could not be a defense to murder (Fickling 2006).

Obviously, “chewing penis” is neither the only nor chiefly objectionable activity that went down that eventful night, though I imagine the subheading grabbed your attention. Yet the incident—explosively reported alike in popular media (e.g., Eckardt 2004; Bovsun 2015) and in academic journals (e.g., Bergelson 2007, 166–67; Y. Lee 2007, 2982–88)—flags three dilemmas: the first on the limits of consent, the second on the normative significance of bodily injury, and the third on the multiple meanings of penis removal (and death). In truth, these three dilemmas are but shaves off the first: the insufficiency of consent, however valorized and sexified, for adjudicating sexual conduct between or among (the legal fiction of rational, competent, adult) human beings.

The fetishists’ fetishizing of consent looks like this: as consent transforms what would be rape into “sex” (Hurd 2005, 504; Baker 2009, 97), so consent transforms sex with violence, scenes of hierarchy, role-playing, or other forms of explicit power exchange into kink (Weinberg 2016, 15).

For example, in his ethnography of what he terms “dyke + queer BDSM” practitioners, Robin Bauer (2014) reports that “the one feature that all interview partners agreed was crucial for an activity to count as BDSM [was] consent” (13). Bauer quotes well-known practitioners who insist, against charges of sadomasochistic sex as violence, that “what we are doing is consensual. Period” (Moser and Madeson 1996, 71, quoted in Bauer 2014, 75).

For another example, in her visual and discursive analysis of kink and black female sexuality, Ariane Cruz (2016), even as she demagnetizes consent from its presumptive normativity, nonetheless reports that “black women BDSMers suggest that [. . .] consent is not only possible but also pleasurable and affectively empowering” (45).2

For a third, acute example of consent fetish, consider the words of well-known kink practitioner and advocate Carol Truscott (1991): “Consensual sadomasochism has nothing to do with violence. Consensual sadomasochism is about safely enacting sexual fantasies with a consenting partner. Violence is the epitome of nonconsensuality” (30).

And for a fourth and final example of consent’s staying power over kink community and politics, visit the National Coalition for Sexual Freedom’s (NCSF’s) “Consent Counts” project site.3 Founded in 1997, NCSF is a nationwide kink support and advocacy coalition that has, over the past few years, initiated its Consent Counts project, which “seeks to decriminalize consensual BDSM which does not result in the infliction of serious bodily injury” (NCSF 2013). Toward that effort, NCSF has filed amicus briefs in cases involving allegedly consensual kink, has petitioned state legislatures, and has lobbied the American Law Institute to recommend that BDSM conduct be permitted a consent defense under the revised Model Penal Code (more on the Model Penal Code below). “It’s all about consent,” the coalition’s website asserts, “and the law should reflect that” (NCSF n.d.).

Let us assume, in light of these four examples, that Bernd Brandes consented with sound mind to the removal of his penis and his death at the hands of Armin Meiwes. Let us assume too that neither intoxicants nor blood loss corroded Brandes’s consent, for “sooner or later we are doomed to encounter a mentally competent person who would wish to be killed or injured” (Bergelson 2007, 186; see also Baker 2009, 103–4). Whether conceptualized as a moral concept or a legal construct, consent is unhelpful for indicting this cannibalistic erotic encounter, an encounter that strikes me as, without question, morally and legally indictable, unless one adopts the most stringent libertarian posture (to be fair, NCSF argues for consent as a defense to kink that “does not result in serious bodily injury,” a qualifier that I will argue in the third section is necessary yet overinclusive and underinclusive; NCSF 2015). The German Cannibal case readily reveals that consent cannot be dispositive; it cannot be sufficient (Westen 2004, 129). The case also reveals that a definitional core of BDSM is readily confused as an ethical core (Hanna 2001, 240). For if we are disinclined to green-light non-eroticized but consensual activity involving gross or even fatal injuries, why should sex make all the difference? If I ask my friend to push me off a skyscraper, most would agree that she should not do so, and that if she did so, my asking to be pushed might mitigate but not eliminate any responsibility on her part (Bergelson 2007, 236; Hanna 2001, 241). Are we really willing to say that if pushing me off the building aroused me (or her), the push (and death) would be morally kosher (Baker 2009, 97–98; McGregor 2005, 243)? Why should “sex”—or sexualizing, really—be so transformative? It should not, even accounting for the specialness sex and intimacy find in many people’s lives (and in the U.S. Constitution; see Lawrence v. Texas [2003]; cf. Spindelman 2003). Indeed, courts in the United States and elsewhere have generally agreed on this point when ruling on cases involving BDSM sex (or rather, cases involving consent as a defense to alleged BDSM sex). In Anglo-American jurisdictions, defendants are usually charged with some form of assault (not sexual assault), for which consent is typically not recognized as a defense (Haley 2014, 636–40; NCSF 2015).

Some critics contend that prosecuting BDSM as assault rather than sexual assault delegitimizes BDSM sex as sex (e.g., Haley 2014, 640–41; Kaplan 2014, 121–22). On this reading, it is not that the legal classification of BDSM as assault reflects the assaultive social reality of BDSM sex but that the legal classification of BDSM as assault purposively discards the sexual social reality of BDSM sex.

Other critics have pointed out that judicial findings of harm (under allegedly consensual circumstances) are thinly guised pretexts for eroto- and homophobia (Khan 2014, 225–303). This judicial sleight of hand is nowhere more infamously on display than in the “Spanner” case in the United Kingdom, in which several men were convicted on various counts of assault for engaging in rough, kinky sex with a younger, submissive man (R. v. Brown [1994]). The graphically described conduct (for example, sterilized fishhooks inserted into the submissive’s penis) is discomfiting, but the injuries sustained were neither permanent nor incapacitating postcoitus (Egan 2006, 1615, 1629). Moreover, despite gestural concern for the welfare of the submissive (who refused to testify against the defendants), the justices’ statements drip with derision, homophobia, and AIDS panic.4 Adding heteronormative insult to queer injury, a defendant was held not guilty of similar conduct (for example, branding the alleged victim’s buttocks) three years later, in large degree because the victim was a woman and the defendant’s wife (R. v. Wilson [1996]; Khan 2014, 237–42). In US jurisdictions, kink advocates point to cases in which defendants have been charged, and some convicted, for assault despite the fact that the BDSM activity did not reach the “serious bodily injury” threshold of the criminal statute. “In one case—particularly notorious in the BDSM community—a woman was prosecuted for assault for consensually spanking another woman with a wooden spoon” (NCSF 2015). The harm of an activity (nipple clamping, for example) is moralistically overstated as “serious” in order to classify it as assaultive (Kaplan 2014, 122; NCSF 2015).

I recount these sex-positive objections to concede that my seemingly simple normative claim—consent, on its own, should not morally or legally green-light any eroticized activity whatsoever, however injurious or impeding—is proposed not in a social vacuum but against a sexual regulatory landscape historically hostile to sexual minorities. Yet bad cases make for bad normative propositions.5 Law professor Cheryl Hanna (2001) points out that the Spanner case is an outlier, “sensational and rare” (263). In most cases in the United States and Canada, the facts follow this pattern: the defendant—almost always male—alleges the conduct in question to have been rough sex that the victim—almost always female—consented to (“asked for”). “In the vast majority of cases that make it into the criminal justice system, consent is questionable at best” (Hanna 2001, 248). In these cases of likely rape, prosecutors charge defendants with assault, not sexual assault, effectively bypassing the he said–she said dispute that women typically lose (Hanna 2001, 269–70; see also State v. Gaspar [2009]).6 One might take issue with this prosecutorial reach-around, and one might concede that phobia underwrites too much judicial reasoning about sex, but Hanna’s observation reveals that the paradigmatic “BDSM case” that makes its way to appellate courts is not kinky-consensual-sex-that-judges-and-juries-are-repulsed-by but rather rape-that-men-claim-as-rough-sex (see also McGregor 2005, 245; Westen 2004, 71–74). In any case, however we come down on these judicial opinions and prosecutorial practices, the central conceptual point I wish to press remains unchallenged: consent, on its own, is insufficient to exonerate any and all forms of sexualized conduct.

One could claim that I am caricaturing the BDSM position, as there are other tools in the kink toolbox besides consent with which to scrutinize erotic cannibalism and erotic murder. BDSM communities have long been in the business of moral advertising to countervail dominant misperceptions and misrepresentations of kink. BDSM’s most widely recognized and longest-running public campaign is SSC, which stands for “safe, sane, and consensual” (d. stein n.d.; Langdridge and Barker 2007).7...

Table of contents

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: When Consent Isn’t Sexy

- 1. Kink and Cannibals, or Why We Should Probably Ban American Football

- 2. The Trouble with Mothers’ Boyfriends, or Against Uncles

- 3. The Trouble with Transgender “Rapists”

- 4. Horses and Corpses: Notes on the Wrongness of Sex with Children, the Inappositeness of Consent, and the Weirdness of Heterosomething Masculinity

- 5. Cripping Consent: Autonomy and Access

- Conclusion: #MeFirst—Undemocratic Hedonism

- Appendices

- Notes

- Court Cases Cited

- Bibliography

- Index

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Screw Consent by Joseph J. Fischel in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Law & Gender & The Law. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.