eBook - ePub

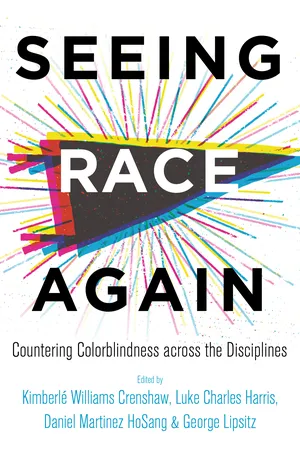

Seeing Race Again

Countering Colorblindness across the Disciplines

- 432 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

Every academic discipline has an origin story complicit with white supremacy. Racial hierarchy and colonialism structured the very foundations of most disciplines’ research and teaching paradigms. In the early twentieth century, the academy faced rising opposition and correction, evident in the intervention of scholars including W. E. B. Du Bois, Zora Neale Hurston, Carter G. Woodson, and others. By the mid-twentieth century, education itself became a center in the struggle for social justice. Scholars mounted insurgent efforts to discredit some of the most odious intellectual defenses of white supremacy in academia, but the disciplines and their keepers remained unwilling to interrogate many of the racist foundations of their fields, instead embracing a framework of racial colorblindness as their default position.

This book challenges scholars and students to see race again. Examining the racial histories and colorblindness in fields as diverse as social psychology, the law, musicology, literary studies, sociology, and gender studies, Seeing Race Again documents the profoundly contradictory role of the academy in constructing, naturalizing, and reproducing racial hierarchy. It shows how colorblindness compromises the capacity of disciplines to effectively respond to the wide set of contemporary political, economic, and social crises marking public life today.

This book challenges scholars and students to see race again. Examining the racial histories and colorblindness in fields as diverse as social psychology, the law, musicology, literary studies, sociology, and gender studies, Seeing Race Again documents the profoundly contradictory role of the academy in constructing, naturalizing, and reproducing racial hierarchy. It shows how colorblindness compromises the capacity of disciplines to effectively respond to the wide set of contemporary political, economic, and social crises marking public life today.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Seeing Race Again by Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Discrimination & Race Relations. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

ONE

Introduction

Kimberlé Williams Crenshaw, Luke Charles Harris, Daniel Martinez HoSang, and George Lipsitz

The essays in this volume reflect and engage the profoundly contradictory role of the university in constructing, naturalizing, and reproducing racial stratification and domination. Stretching from the racially specific projects of the past to the colorblind conventions of academic performance today, leading scholars in the social sciences, law, and humanities reveal in this book how disciplinary frameworks, research methodologies, and pedagogical strategies have both facilitated and obscured the social reproduction of racial hierarchy. The indictment of the knowledge-producing industry contained in these pages uncovers the chapters of racial history that remain undisturbed behind the walls of disciplinary convention and colorblind ideology. At the same time, the conditions of possibility out of which these essays were produced situate the university as a site in which antiracist projects can be seeded and developed. The disciplines not only produce racial power and inhibit racial knowledge, they also offer discursive tools and analytic moves that, properly contextualized, enable and enhance the telling of race and the reimagination of racial justice. In grappling with this duality, this collection embodies the twin objectives of the Countering Colorblindness project: to unpack and disrupt the racial foundations of the disciplines, and to aggregate and repurpose disciplinary insights into an alternative understanding of the social world.

This volume amplifies the methods and challenges that are foundational to critical race projects that interrogate the epistemic parameters of racial power in order to enable emancipatory possibilities both within the academy and in the social world beyond. Countering Colorblindness transcends the institutional and discursive boundaries that contain racial knowledge in multiple ways. The project is first and foremost transdisciplinary. The story it tells about the foundations of racial hierarchy and its contemporary disavowals across the university—in particular the traveling and uptake of particular orientations toward race between disciplines—can only become fully legible through the aggregated sum of its disciplinary parts. One cannot, for example, understand the narrowed ways in which racism has come to be imagined within law as the bigotry of specific individuals without engaging similar containments within sociology, social psychology, and the like.

Countering Colorblindness, however, transcends not only boundaries within the university, but boundaries between the university and civil society more broadly. The contemporary social conditions shaped by histories of white supremacy—education, health, criminal justice, employment, housing—are linked to the construction and disavowal of race within the academic disciplines themselves. Most institutions are now formally organized around the untested assumption that colorblindness is the exclusive measure of a fair and just organizational practice, an assumption that is predicated on and enabled by the privileging of colorblind solutions to color-bound problems within scholarly disciplines. Questions of racial discrimination, inequity, and injustice are typically framed as problematic only to the extent that the troubling conditions can be attributed to contraventions against the colorblind ideal. This resort to colorblindness is not solely an institutional-level response. As Eduardo Bonilla-Silva’s work has long documented, individuals now defend themselves against the slightest intimation that their preferences or decisions might be racially inflected with the all-purpose disclaimer that they neither see race nor take it into account.1

As a political project, colorblindness derives from a seeming naturalness and inevitability. It resonates with time-honored practices and ideals in Western thought and social relations. A long history of artistic expression and humanities scholarship has grounded aspirations for social justice in the elision of difference. The market subject of classical capitalist theory, the citizen subject of liberalism—and even the universal worker of Marxism and the universal woman of feminism—all rest upon an ideal of interchangeability wherein differences are said not to matter. These traditions teach that similarity should trump difference; that beneath the surface the appearance of “otherness” masks a common human condition.

Although many humane and egalitarian projects in history have been based on humanist concepts of liberal interchangeability, contemporary scholars have raised questions about the dangers of ignoring fundamental differences, particularly distinctions linked to social position, vulnerability, and power. While conceding that all of our fates are linked and acknowledging the sordid histories of parochial particularism, these scholars contend that some important differences do not disappear simply by affirming sameness. Furthermore, the identities celebrated as universal by the standards of humanism and liberalism are almost always actually dominant particulars masquerading as universals. Indeed, the abstract assertions of human interchangeability in law, economics, and politics tend to serve as mechanisms for occluding the seemingly endless differentiations, inequalities, and injustices of existing social relations.

In postulating a common human experience, many great traditions in art, law, and politics celebrate the symbolic transcendence of difference without offering or even suggesting the need for access to equitable opportunities or conditions. In these settings, differences become contaminated with a menacing otherness, an otherness that threatens the promise of an ideal egalitarian future. People with problems thus become identified as problems; and the members of groups who object to social inequality then become castigated for calling attention to differences that matter in their lives.

These perspectives make colorblindness seem a laudable goal. They make it appear as though the solution to vexing problems of difference is to simply stop acknowledging such differences. In this way, they cover over embodied inequalities with a disembodied universalism. Perhaps most importantly, they locate questions of social justice in a stark choice between egalitarian universalism on the one hand and a putatively parochial and prejudiced particularism on the other.

Against this deep philosophical background, today’s colorblindness easily trumps race-conscious interventions as more appealing and ultimately morally just. As a consequence, efforts to sustain investment in race-conscious research and policy face an uphill battle. A telling example of the malaise that exists in social justice discourse can be found in the ineffective efforts of social justice advocates to push back against colorblindness with concepts and strategies that are at best anachronistic. Moreover, much of the policy that is the object of policy debates bows to the colorblind imperative in the final analysis. As the legal scholar Mark Golub explains, “Anti-racist criticism too often has been defined by the object of its critique, and so offers inadequate tools for resisting it. Even when it is rejected, that is, color-blindness discourse sets the terms of debate, defines normative goals, and limits the scope of legitimacy for alternative formulations of racial justice.”2 In his exemplary research, however, Golub deploys careful, critical, and detailed analyses of landmark Supreme Court cases to reveal how the ideal of colorblindness as the default position for social justice actually functions as a color-conscious tool crafted to protect white preferences and privileges.

As colorblindness becomes increasingly entrenched as the common denominator in efforts to deny and transcend racial power, the parameters of racial discourse between the university and the general public reveal an interdependent relationship that is far closer than scholars often acknowledge. Colorblindness operates as the default intellectual and ethical position for racial justice in many corners of the academy and in public policy, imposing profound limitations on scholars, students, and the wider public. The compromised capacity of disciplines to respond effectively to the wide set of political, economic, and social problems that mark public life today demand new strategies that situate a critical understanding of race and racism at the center of knowledge production and public engagement.

Despite colorblindness’s appearance as a commonsense value and practice, it is an idea sustained more by the repetition of its use and by the power of those who invoke it than by a firm basis in reality, research, theory, or for that matter, the Constitution. Indeed, scholars from a variety of disciplines have produced powerful studies that contest its viability as a definitive determinant of social justice. This research disproves some of the central claims made for colorblindness, and casts considerable doubt about how a future wrapped around this ideal will unfold.

Yet even apart from this research, colorblindness at the most basic level mobilizes a metaphor of visual impairment to embrace a simplistic and misleading affirmation of racial egalitarianism. Its emphasis on color imagines racism to be an individualistic aversion to another person’s pigment rather than a systemic skewing of opportunities, resources, and life chances along racial lines. The blindness part of the metaphor presumes that visually impaired people are incapable of racial recognition and that recognition itself is the problem that racism presents. Yet as the research of Osagie K. Obasogie establishes, visually impaired people hold the same understandings of race that sighted people possess. They are neither more nor less likely to engage in racist judgments.3 Moreover, visually impaired people who are white enjoy the unfair gains, unjust enrichments, and unearned status of whiteness, while those who are people of color experience the artificial, arbitrary, and irrational impediments caused by racism and social prejudices against disability. Not only must the logic and salience of colorblindness as a metaphor be rejected, but so must the presumptions about normativity and disability that underwrite it.

Given the slender reed upon which the weighty denial of racial power rests, one might think that a powerful antidote to the widespread use of colorblindness might arise fully activated from the knowledge-producing industry. But despite the depth of scholarly understanding about the inadequacies of colorblindness as a theory, policy, cognitive possibility, or constitutional principle, this canon has gained little traction in efforts to draw attention to the racist realities that the colorblind perspective works to obscure. Consequently, the wealth of information produced in the academy pertaining to race—historical, economic, sociological, psychological, literary, and legal—has yet to converge into a coherent commonsense understanding of the world that we live in. Indeed, far from countering colorblindness, the prevailing practices around which privileged knowledge is produced and authorized operate to enhance the stabilizing dimensions of colorblind discourse. Thus, countering colorblindness requires an interrogation into the disciplinary, cultural, and historical dynamics that sustain a disaggregated, partial, and parochial knowledge base about one of the most vexing societal problems of our time.

The failure of the disciplines to produce a collective accounting of the realities of race in contemporary society occludes the more fundamental indictment upon which countering colorblindness rests. Behind the colorblind f...

Table of contents

- Imprint

- Subvention

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface and Acknowledgments: Praying to the Disciplinary Gods with One Eye Open

- 1 • Introduction

- Part One: Masks

- Part Two: Moves

- Part Three: Resistance and Transformation

- List of Contributors

- Index