- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

In this monumental, authoritative history of Afghanistan, now updated, Jonathan L. Lee places the current conflict in its historical context and challenges many of the West's preconceived ideas about the country. Lee chronicles the region's monarchic rules and the Durrani dynasty, focusing on the reigns of each ruler and their efforts to balance tribal, ethnic, regional and religious factions, moving on to the struggle for social and constitutional reform and the rise of Islamic and Communist factions. He offers new cultural and political insights from Persian histories, the memoirs of Afghan government officials, British government and India Office archives, recently released CIA reports and WikiLeaks documents. Lee also sheds new light on the country's foreign relations, its internal power struggles and the impact of foreign military interventions such as the War on Terror.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

ONE

Afghan Sultanates, 1260–1732

The fame of Bahlol and of Sher Shah too, resounds in my ears Afghan Emperors of India, who swayed its sceptre effectively and well. For six or seven generations, did they govern so wisely, That all their people were filled with admiration of them. Either those Afghans were different, or these have greatly changed.

KHUSHHAL KHAN KHATTAK

Amongst the Afghan tribes it is indisputable that where one [tribe] possesses more men than the other, that tribe will set out to destroy the other.

SHER SHAH SURI1

MODERN HISTORIES of Afghanistan generally regard 1747 as the founding date of the modern state of Afghanistan.2 This is because in that year Ahmad Shah, a young Afghan of the ‘Abdali tribe, who later adopted the regnal name of Durrani, established an independent kingdom in Kandahar and founded a monarchy that, in one expression or another, ruled Afghanistan until 1978. In fact the history of Afghan rule in the Iranian–Indian frontier can be traced back many centuries before the birth of Ahmad Shah. Nor was Ahmad Shah the first Afghan, or member of his family or tribe, to rule an independent kingdom.

In 1707 Mir Wa’is, of the Hotak Ghilzai tribe of Kandahar, rebelled against Safavid Persia and founded a kingdom that lasted for more than thirty years. In 1722 Mir Wa’is’ son, Shah Mahmud, even invaded Persia and displaced the Safavid monarch and for seven years ruled an empire that stretched from Kandahar to Isfahan. Even after Mir Wa’is’ descendants were thrown out of Persia, they continued to rule Kandahar and southeastern Afghanistan until 1738.

In 1717, ten years after Mir Wa’is’ revolt, a distant cousin of Ahmad Shah, ‘Abd Allah Khan Saddozai, established the first independent ‘Abdali sultanate in Herat after seceding from the Safavid Empire and for a brief period both Ahmad Shah’s father and half-brother ruled this kingdom. The dynasty founded by Ahmad Shah in 1747 lasted only until 1824, when his line was deposed by a rival ‘Abdali clan, the Muhammadzais, descendants of Ahmad Shah’s Barakzai wazir, or chief minister. In 1929 the Muhammadzais in turn were deposed and, following a brief interregnum, another Muhammadzai dynasty took power, the Musahiban. This family was the shortest lived of all three of Afghanistan’s ‘Abdali dynasties: its last representative, President Muhammad Da’ud Khan, was killed in a Communist coup in April 1978. All these dynasties belonged to the same Durrani tribe, but there was little love lost between these lineages. Indeed, the history of all the Afghan dynasties of northern India is turbulent and their internal politics marred by feuds and frequent civil wars.

While dozens of tribes call themselves ‘Afghan’, a term which nowadays is regarded as synonymous with Pushtun, Afghanistan’s dynastic history is dominated by two tribal groupings, the ‘Abdali, or Durrani, and the Ghilzai. The Ghilzai, or Ghilji, as a distinct tribal entity can be traced back to at least the tenth century where they are referred to in the sources as Khalaj or Khallukh. At this period their main centres were Tukharistan (the Balkh plains), Guzganan (the hill country of southern Faryab), Sar-i Pul and Badghis provinces, Bust in the Helmand and Ghazni. Today the Ghilzais are treated as an integral part of the Pushtun tribes that straddle the modern Afghan–Pakistan frontier, but tenth-century sources refer to the Khalaj as Turks and ‘of Turkish appearance, dress and language’; the Khalaj tribes of Zamindarwar even spoke Turkish.3 It is likely that the Khalaj were originally Hephthalite Turks, members of a nomadic confederation from Inner Asia that ruled all the country north of the Indus and parts of eastern Iran during the fifth to early seventh centuries CE.4 The Khalaj were semi-nomadic pastoralists and possessed large flocks of sheep and other animals, a tradition that many Ghilzai tribes have perpetuated to this day.

The Khalji Sultanates of Delhi

During the era of the Ghaznavid dynasty (977–1186), so named because the capital of this kingdom was Ghazni, the Khalaj were ghulams, or indentured levies, conscripted into the Ghaznavid army.5 Often referred to as ‘slave troops’, ghulams were commonplace in the Islamic armies well into the twentieth century, the most well known being the Janissaries of the Ottoman empire. Ghulams, however, were not slaves in the European sense of the word. Unlike tribal levies, whose loyalties were often to their tribal leaders rather than the monarch, ghulams were recruited from subjugated populations, usually non-Muslim tribes, forced to make a token conversion to Islam and formed the royal guard of the ruling monarch, or sultan. The ghulams thus provided a ruler with a corps of loyal troops that were bound to him by oath and patronage and that offset the power of the sultan’s tribe and other powerful factions at court.

The minaret of the Ghaznavid Sultan Bahram Shah (1084–1157), one of two surviving medieval minarets outside Ghazni.

The ghulams were generally better trained and armed than any other military force in the kingdom and were the nearest thing to a professional army. Their commanders enjoyed a privileged status, often held high office and owned large estates. In a number of Muslim countries ghulams eventually became so powerful that they acted as kingmakers and on occasion deposed their master and set up their own dynasty. The Ghaznavids were a case in point. Sabuktigin (942–997), a Turk from Barskon in what is now Kyrgyzstan, who founded this dynasty, was a ghulam general who was sent to govern Ghazni by the Persian Samanid ruler of Bukhara, only for him to eventually break away and set up his own kingdom.6

Given that the Khalaj in the Ghaznavid army are referred to as ghulams it is very likely that they were one of many kafir or pagan tribes that lived in the hill country between the Hari Rud, Murghab and Balkh Ab watersheds. In 1005/6 Sultan Mahmud, the most famous of the Ghaznavid rulers, invaded, subjugated and systematically Islamized this region. As part of the terms of submission, the local rulers would have been required to provide a body of ghulams to serve in the Ghaznavid army. The Khalaj soon proved their worth, repelling an invasion by another Turkic group, the Qarakhanids, and subsequently in campaigning against the Hindu rulers of northern India.

In 1150 Ghazni was destroyed by the Ghurids, a Persian-speaking dynasty from the hill country of Badghis, Ghur and the upper Murghab, and by 1186 all vestiges of Ghaznavid power in northern India had been swept aside. The Ghurids incorporated the Khalaj ghulams into their army and it was during this era that they and probably the tribes of the Khyber area began to be known as Afghan, though the origin and meaning of this term is uncertain. Possibly Afghan was a vernacular term used to describe semi-nomadic, pastoral tribes, in the same way that today the migratory Afghan tribes are referred to by the generic term maldar, herd owners, or kuchi, from the Persian verb ‘to migrate’ or ‘move home’. It was not until the nineteenth century and under British colonial influence that Afghans were commonly referred to as Pushtun or by the Anglo-Indian term Pathan.

During the Ghaznavid and Ghurid eras many Khalaj and other Afghan clans were relocated around Ghazni, others were required to live in the Koh-i Sulaiman, or in the hinterland of Kandahar, Kabul and Multan, where they were assigned grazing rights. This relocation may have been a reward for their military service, but more likely it was a strategic decision, since it meant these tribes could be quickly mustered in the event of war. By the early fourteenth century Afghans were a common feature of the ethnological landscape of southern and southeastern Afghanistan. The Arab traveller Ibn Battuta, who visited Kabul in 1333, records how the qafila, or trade caravan, he was travelling with had a sharp engagement with the Afghans in a narrow pass near the fortress of ‘Karmash’, probably on the old Kabul–Jalalabad highway.7 Ibn Battuta damned these Afghans as ‘highwaymen’, but on the basis of the limited sources available it is likely these tribes expected payment for safe passage and the head of the caravan had failed to pay the customary dues. Significantly, Ibn Battuta notes that the Afghans of the Kabul–Jalalabad region were Persian-speakers, though whether they spoke Pushtu too is not recorded.

Other sources from this era portray the Afghans as a formidable warrior race. One author graphically compares them to ‘a huge elephant . . . [a] tall tower of a fortress . . . daring, intrepid, and valiant soldiers, each one of whom, either on mountain or in forest, would take a hundred Hindus in his grip, and, in a dark night, would reduce a demon to utter helplessness’.8 These Afghan ghulams certainly lived up to this reputation during their campaigns in India and the Ghurids rewarded their commanders with hereditary estates, or jagirs, in the plains of northern India. This led to a substantial migration of Afghan tribes from the hill country of what is now south and southwestern Afghanistan to the fertile, frost-free and well-watered lands of the Indian plains. Eventually the Khalaj, by this time referred to as the Khaljis or Khiljis, became so powerful that they placed their own nominee on the throne of Delhi. In 1290 they seized power and for the next thirty years ruled northern India in their own right.

The Khaljis and other Afghan tribes kept apart from their mostly Hindu subjects, living in cantonments, or mahalas, based on clan affiliation. Jalal al-Din Firuz, the first Khalji sultan, even refused to attend the court in Delhi and built a new capital a few kilometres away in the Afghan enclave of Kilokhri.9 This cultural isolation was reinforced by the practice of endogamy, for the Khalji would only marry women from their own tribe. As for the Khalji tribal leaders, they showed scant respect for the authority of the sultan and there were frequent clashes between them and the crown as the former fought the monarch’s efforts to curb their traditional right to the autonomous government of their tribes.10 The Khalji were also notorious for their blood feuds, which they pursued regardless of the consequences to the body politic. Rivals even fought each other in the court and, on one occasion, in the royal presence itself. The Khalji, however, were also a formidable military power. Sultan Jalal al-Din Firuz (r. 1290–96) and his successor Sultan ‘Ala’ al-Din, or Juna Khan (r. 1296–1316) even defeated the invading Mongol armies on several occasions and in so doing saved northern India from the ravages they inflicted on Afghanistan, Persia and the Middle East.

The last Khalji, Sultan Ikhtiyar al-Din, was assassinated in 1320 and a Turkish dynasty, the Tughlaqs, seized power, but the Afghans remained a force in the political and military life of northern India. Between 1436 and 1531 one branch of the Khalji dynasty ruled Malwa in modern Madhya Pradesh, while thousands of Khaljis owned large tracts of land in western India and dozens of their military cantonments were scattered throughout northern India from the Punjab to Bengal. The Afghans also continued to provide high-quality troops for the Tughlaq army and some held high military office.

In 1451 Bahlul Khan, an Afghan of the Lodhi clan, deposed the then sultan and founded a second Afghan sultanate, the Lodhi Dynasty, which ruled northern India for 75 years (1451–1526). Under the Lodhis, another wave of Afghans migrated into northern India and perpetuated the tradition of living in separate cantonments and the practice of endogamy. Ludhiana, now close to the frontier between India and Pakistan, for example, derives its name from having originally been a Lodhi cantonment. The Lodhis, while Muslims, were still only semi-Islamized. After Sultan Bahlul Lodhi conquered Delhi he and his followers attended Friday prayers in the main mosque to ensure that his name was recited in the khutba, which was an essential act of the Friday congregational prayer service. The imam, or prayer leader, observing how the Afghans struggled to perform the prayers according to prescribed rituals, was heard to exclaim: ‘what a strange (‘ajab) tribe has appeared. They do not know whether they are followers of Dajal [the Antichrist] or if they are themselves Dajal-possessed.’11

The Mughal conquest of India and Afghan–Mughal rivalry

The Lodhi dynasty came to an abrupt end at the Battle of Panipat in 1526, when the last sultan was defeated by the Mughal armies of Zahir al-Din Babur. Babur, a descendant of both Timur Lang and Chinggis Khan, thus became the latest in a series of Turkic rulers of India whose empire included Kabul and southeastern Afghanistan. Born in Andijan in the Fergana Oasis of what is now Uzbekistan, Babur’s father had ruled a kingdom that included Samarkand and Bukhara, but after his death Babur had been ousted from the region by the Shaibanid Uzbeks and fled across the Amu Darya, eventually taking Kabul from its Timurid ruler. Prior to his invasion of India, Babur had conducted a series of expeditions against the Afghan tribes of Laghman and Nangarhar as well as the Mohmands of the Khyber area, and the Ghilzais of Ghazni.12

Following his victory at Panipat, Babur did his best to reconcile the Afghan tribes that lay across the key military road between Kabul and the Punjab. To this end he married Bibi Mubaraka, daughter of Malik Shah Mansur Yusufzai, a member of one of the most powerful and numerous Afghan tribes. Dilawar Khan Lodhi, a member of the deposed dynasty, also became one of Babur’s most trusted advisers and was given the hereditary title of Khan Khanan, Khan of Khans. Other members of the Lodhi dynasty were appointed as governors or held high rank in the army. Despite this, there were numerous Afghan rebellions against Mughal rule. In 1540, following Babur’s death, there was civil war between his sons and eventually Farid al-Din Khan, an Afghan of the Suri clan, who had been a high-ranking officer under the Lodhis, ousted Babur’s son and successor Humayun from Delhi, and adopted the regnal title of Sher Shah Suri. The Sur dynasty Sher Shah Suri founded ruled much of northern India from 1540 to 1555. Humayun himself fled to Persia but after fifteen years in exile he finally regained the throne of Delhi and restored the Mughal supremacy.

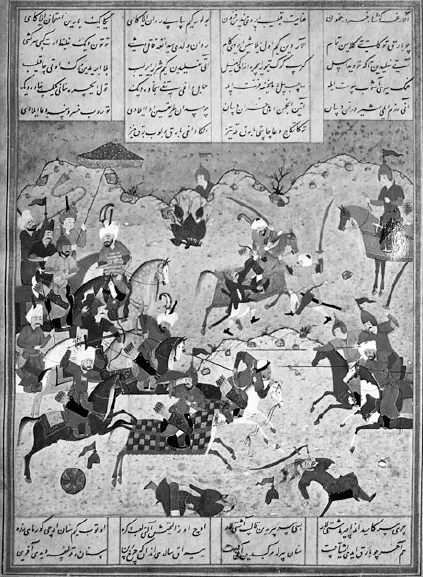

A Timurid miniature from Herat, early 16th century, depicting a battle scene.

Sher Shah Suri’s rebellion hardened Mughal attitudes towards the Afghan tribes. Humayun’s son and heir, Akbar the Great (r. 1556–1605), confiscated their jagirs and banned them from governorships and high military rank. Racial prejudice too ran deep, with Mughal historians regularly referring to Afghans as ‘black-faced’, ‘brainless’, vagabond’ and ‘wicked’.13 The suppressions, confiscations and general prejudice caused deep resentment, for many Afghans continued to serve the Mughal empire faithfully.

One response to this disenfranchisement was the rise of a militant millenarian movement known as the Roshaniyya (Illuminated), which posed a serious threat to Mughal rule in northwestern India for almost half a century.14 Its founder, Bayazid Ansari (1525–1585), or Pir Roshan, was fro...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Half Title

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- LIST OF CHARTS, TABLES AND MAPS

- TRANSLITERATIONS

- Preface to the Paperback Edition

- Introduction

- 1. Afghan Sultanates, 1260–1732

- 2. Nadir Shah and the Afghans, 1732–47

- 3. Ahmad Shah and the Durrani Empire, 1747–72

- 4. Fragmentation: Timur Shah and His Successors, 1772–1824

- 5. Afghanistan and the Indus Frontier, 1824–39

- 6. The Death of the ‘Great Experiment’, 1839–43

- 7. The Pursuit of ‘Scientific Frontiers’, 1843–79

- 8. ‘Reducing the Disorderly People’, 1879–1901

- 9. Reform and Repression, 1901–19

- 10. Dreams Melted into Air, 1919–29

- 11. Backs to the Future, 1929–33

- 12. A House Divided, 1933–73

- 13. Republicanism, Revolution and Resistance, 1973–94

- 14. ‘Between the Dragon and His Wrath’, 1994–2017

- Conclusion

- Afghanistan, 2017–21: A Reflection

- GENEALOGICAL CHARTS

- GLOSSARY

- A NOTE ON SOURCES

- REFERENCES

- SELECT BIBLIOGRAPHY

- ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- PHOTO ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

- INDEX

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Afghanistan by Jonathan L. Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Central Asian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.