![]()

ONE

THE SCINTILLATING ONE

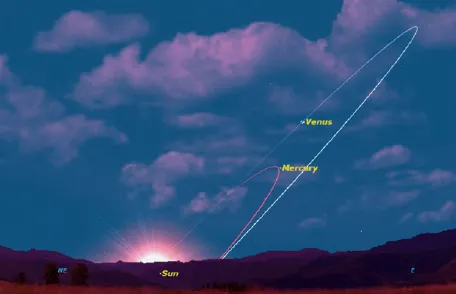

Elusive in the glow of twilight, Mercury never strays more than 28 degrees from the Sun, so that whenever it ventures to appear it is only as an elusive intruder into our skies that never skims far above the rooftops or hedges. It rises at most two hours before sunrise and sets two hours after sunset, so that it must be seen through the full thickness of the Earth’s atmosphere. At such times the small size of its planetary disc and the tumult of the air combine to set it to twinkling. Noticing this, the ancient Greeks referred to it as Stilbon – the ‘scintillating one’.

It used to be claimed that Nicolaus Copernicus (1473–1543) never saw it during his lifetime, owing to mists rising from the Frisches Haff near Frauenberg (now Frombork, Poland), in whose cathedral he was a canon. But the story is baseless – after all, as a young man Copernicus spent many years in the favourable climate of Italy, where conditions for viewing Mercury are better than in Poland. In England, conditions are more like those in Poland than Italy; thus a seventeenth-century writer, Goud, claimed that Mercury was an impious lackey of the Sun who rarely showed his head in England, rather like one on the run from his debtors.

In contrast to the Copernicus legend is the story of Gallet, a seventeenth-century cleric at Avignon, who was nicknamed the ‘Hermophile’ because he managed to see the planet with the naked eye more than a hundred times during his lifetime. Gallet’s record may have been good for conditions in southern France, but most alert amateurs will have easily exceeded it in a few years of observation.

|

Mercury, the swift-of-foot messenger god, seen here in Glasgow, Scotland. |

The trick to seeing Mercury is looking at the right times and having a reasonably unobstructed tour d’horizon. It is more often seen, no doubt, than recognized. Despite its supposed difficulty of detection, Mercury ranks among the planets known since earliest times. The fact that it was recognized by many of the star-watching peoples of antiquity is testified by the succession of names they gave to it. The ancient Egyptians, who apparently recognized that Mercury, like Venus, moves round the Sun, called it Sobkou. It was also known in the Nile Valley by a name equivalent to that of the Greek Apollo. The Sumerians called it Bi-ib-bou, the Assyrians and Chaldeans named it Goudoûd, while the Babylonians knew it as Sekhès, and Ninob, Nabou or Nebo. According to Eugène Michel Antoniadi, the last three signified that it was possessed of great and exceptional intelligence. Indeed, Nabou seems to have been the ruler of the universe, since he alone could raise the Sun from its bed.1

Venus, Mercury and the crescent Moon make a triangle in the sky. Mercury is the lowest, dimmest ‘star’, barely visible as a tiny dot to the left of the dark cloud. |

|

The orbits of Mercury and Venus, the two planets closer to the Sun than the Earth, shown with respect to our horizon. |

|

Among the Greeks, it was not only Stilbon, the scintillating one, but Hermes, the messenger of the gods of Mount Olympus, who announced the rising of the God of Day. (He is one and the same with the Roman Mercury.)

The observer who succeeds in catching sight of it soon becomes aware of the aptness of these appellatives, for Mercury is a world of rapid movement. The favourable opportunities for catching it occur for a week or two round the greatest elongations east or west of the Sun, which occur an average of six times each year. These elongations are not equally favourable, and because of the inclination of the ecliptic, for northern observers the best times to see the flushed little planet as an evening star occur in the spring, and as a morning star in the autumn, as noted earlier. Its movement from night to night is very evident as it quickly loops outwards from and back towards the Sun. If seen as an evening star, it will not return as an evening star for another 115.9 days (its so-called synodic period).

|

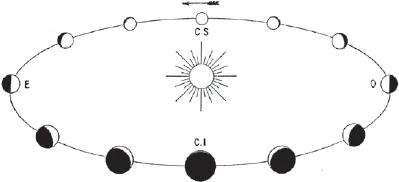

An inferior planet (for example, Mercury) and its positions with respect to the Sun and Earth. Note that maximum elongations bring the planet furthest away from the Sun in our sky. |

![]()

TWO

MOTIONS OF MERCURY

The ancient Greeks held that the Earth was the centre of the universe, and that the Sun and other planets revolved around it. (An exception was Aristarchus of Samos, who in the third century BCE advanced a heliocentric theory in which the Earth was an ordinary planet revolving around the Sun; there were, however, few takers at the time.)

The most elaborate form of the geocentric theory was put forward by Claudius Ptolemy, a Greek astronomer who lived in Alexandria, Egypt, site of the famous library, in the second century CE. His greatest astronomical work is the ή μεγίστη (Syntaxis – later known as the Great Syntaxis to distinguish it from a lesser collection of astronomical writings; the title was later rendered by the Arabs as al-majisti, the Greatest, and translated from Arabic to Latin as the Almagest, by which it is generally known). Next only to Euclid’s Elements, it has the distinction of having been the scientific text longest in use, and for over a thousand years remained the supreme authority on astronomy wherever Greek culture and learning survived.

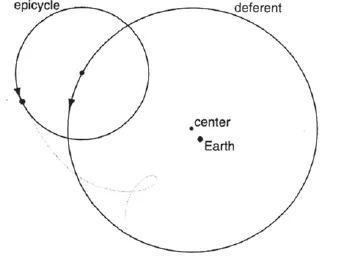

Ptolemy was a synthesizer who perfected the work of his great predecessors, such as Hipparchus of Nicaea (c. 190–c. 120 BCE) and Apollonius of Perga (c. 247–205 BCE), and so successfully that the technical details of their works are largely lost. In order to represent the apparent motions of the planets on the basis of an Earth-centred scheme, they devised a system in which a planet moves in a little circle (known as the epicycle), which in turn moves about a larger circle (the deferent) centred on the Earth. Ptolemy brought this system of epicycles and deferents to its fullest elaboration – thus it is usually referred to as the Ptolemaic system, even though Ptolemy did not, in fact, invent it. In its final form, it was admittedly rather complicated and artificial looking, but it represented the motions of the planets to within the limits of accuracy of the observations at the time, and in those terms it deserves to be judged. The Harvard historian Owen Gingerich has said:

It is difficult to convey the elegance of Ptolemy’s achievement to anyone who has not examined its details. Basically, for the first time in history (so far as we know) an astronomer has shown how to convert specific numerical data into the parameters of planetary models, and from the models has constructed a set of tables that employ some admirably clever mathematical simplifications, and from which solar, lunar, and planetary positions and eclipses can be calculated as a function of any given time.1

Ptolemy deserves special plaudits for his theory for the motion of Mars. Mars’s motions are so complicated that they earned it a reputation (in the first-century CE Roman natural history writer Pliny’s words) as the ‘untrackable star’. Ptolemy inherited from his predecessors the basic epicycle construction (by the same token that Bach inherited the fugue and Beethoven the sonata). It was the way he applied it that was ingenious.

As the epicycle turned, a point on its rim followed a looped path swinging in towards the centre of the larger circle, before moving outwards again in reverse. This rather complicated mechanism was required to explain the so-called retrograde motions of Mars and the other outer planets – around the time the planet appears opposite the Sun in the sky, it seems to move through a backward loop, before resuming its direct motion. As we now know, because Copernicus and Kepler showed us, the retrograde movement is merely a reflection – in the outer planet’s apparent path – of the Earth’s own orbit around the Sun.

Ptolemy’s epicycle-and-deferent model for the observed motion of planets with respect to the Earth. Note that the Earth is stationary in this model. | |

That orbit is actually an ellipse of rather high eccentricity, which makes the speed of Mars’s motion variable. An observable result is that it sometimes moves through its retrograde loops much faster than at others. Ptolemy managed to explain this (within the limits of accuracy of naked-eye observations) by putting his deferent circle slightly off-centre from the Earth, and adjusting it until he had the speed of Mars’s motion just right. Then – and here his tinkering touched on genius – he made it move uniformly not around the centre of the deferent but around another point introduced by Ptolemy in the second century BCE called the equant, so-called because it lay an equal distance on the opposite side of the centre from the Earth (this solution was referred to as the ‘bisection of the eccentricity’).

Gratified by his success with Mars, Ptolemy did not hesitate to apply it to the rest of the planets. He was successful – except in one bedevilling case: Mercury. Here it was the uncertainty of the observations that created difficulties for him. As we now know, Ptolemy would have done perfectly well had he represented Mercury’s motion with the same basic construction he devised for the other planets, but because it is almost impossible to observe in certain positions in its orbit from mid-northern latitudes – particularly at its morning elongations in April and its evening elongations in October – Ptolemy incorrectly deduced that there were two points at which the apparent diameter of Mercury’s epicycle would be greatest as seen from the Earth. To accommodate this assumption, he constructed a hypothesis in which the planet could make two close sweeps to the Earth. It worked just like a crank – the centre of the deferent moving about a little circle and thrusting the epicycle back and forth along a line. One cannot help admiring the Alexandrian astronomer’s ingenuity. Obviously this little planet, ...