eBook - ePub

Inclusive Growth

The Global Challenges of Social Inequality and Financial Inclusion

- 139 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Inclusive Growth

The Global Challenges of Social Inequality and Financial Inclusion

About this book

Inclusive growth ensures the benefits of a growing economy extend to all segments of society. Unleashing people's economic potential starts with connecting them to the vital networks that power the modern economy. Implementing inclusive growth is a means of democratizing productivity and it is essential to reduce the widening gap between the wealthy and the poor in both developed and developing economies.

This book arose out of a research partnership between the Mastercard Center for Inclusive Growth and Singapore Management University (SMU). It demonstrates the logic of inclusive growth, explaining its principles and the enabling models that define it. It also examines the means to creatively address financial and social inclusion and thus improve social equality. The focus is to provide basic rights for all in society to access and participate in the vital networks of services and know-how that are the indispensable enablers of increasing productivity in modern economic production. Business, government, and civil society must devise implement effective initiatives so that inclusive growth is achieved through the global democratization of productivity.

Inclusive Growth: The Global Challenges of Social Inequality and Financial Inclusion will appeal to researchers and faculty in management and business schools, leaders with a moral and ethical sense of social responsibility, as well as academics interested in economics, economic policy, and economic development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Inclusive Growth by Howard Thomas,Yuwa Hedrick-Wong in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Economics & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Enabling Models of Inclusive Growth from Financial Inclusion to Democratizing Productivity

Introduction

The Puzzle of Economic Growth: The Widening Gap between Richer and Poorer Countries

During World War II, a group of Allied airmen who were shot down captured and imprisoned in a Nazi Prisoner of War camp, engineered an ingenious breakout; an event that inspired the 1963 film The Great Escape. It is also the title of a 2013 book by the economics Nobel Laureate Angus Deaton about another extraordinary escape: the decline in global poverty across the world over the last half century.

The full title of Deaton’s book is The Great Escape: Health, Wealth, and the Origins of Inequality (Deaton, 2015). It meticulously documents the economic and social progress made with an abundance of data at both the micro- and macro-levels.

In addition to focusing on standard economic measures Deaton combines data on health with income to create a more holistic perspective; an approach that enables him to assess more rigorously the illusive concept of well-being. The book encapsulates the virtues of vision, rigor, and creativity that Deaton has consistently displayed in his scholarship with the compelling conclusion that the achievement in poverty reduction in the past half century is real and historically unprecedented.

This is corroborated by the progress made in achieving the United Nations Millennium Goal of cutting the 1990 poverty rate in half by 2015. As it turned out, the world achieved this target in 2010, five years ahead of schedule. According to data by the World Bank, nearly 1.1 billion people have been moved out of extreme poverty (defined as living on less than $1.90 a day) since 1990. China in particular was responsible for a significant element of this by lifting almost 400 million out of poverty. In 2013, 767 million people lived on less than $1.90 a day, down from 1.85 billion in 1990 (World Bank Group, 2018).

And yet, in the midst of so much progress, the world remains extremely divided between the rich and the poor with a wide disparity in the “wealth of nations.” For example, in 2015 Switzerland had the highest per capita GDP in the world at $80,802, followed by Norway at $74,342, and the United States at $56,049. In sharp contrast, Burundi had the lowest per capita GDP at $268. The Central African Republic was the second lowest at $325, and Niger the third lowest at $361. In other words, the richest country is 301 times richer than the poorest country on a GDP per capita basis.

Africa accounts for 15 of the 16 countries with the lowest GDP per capita in the world (Afghanistan is the only non-African country in this group) (IMF WEO Data, 2018). And the gap between the richest and poorest countries has continued to widen at the same time that hundreds of millions of people were escaping poverty.

An even more disheartening picture emerges through the lens of “wealth account,” which is a more comprehensive measure than GDP. While GDP is a flow concept, summing up how much is produced, consumed, and invested each year, the wealth account estimates the sum of productive assets in a country.

Four key types of capital are included in the estimate: produced capital (e.g., physical infrastructure, machinery, and tools); financial capital (e.g., net foreign assets); human capital (estimated as the present value of the future earnings of the labor force); and natural capital (the sum of values of natural resources).

While GDP growth fluctuates – often wildly during financial crises – the wealth account of a country is a more stable measure of its growth and development prospects, especially when estimated on a per capita basis.

The latest estimates of wealth per capita, which cover 141 countries over the period 1995–2014, unveil a deeply divided world (Lange, Wodon, & Carey, 2018). There is a significant overlap between countries with the lowest GDP per capita and the lowest wealth per capita. In fact, Burundi, which has the lowest GDP per capita, has also seen its wealth per capita shrink the most among the countries measured during the period. Other sub-Saharan African countries such as Democratic Republic of Congo, Nigeria, Zimbabwe, and Cote d’lvoire also experienced declining wealth per capita. Note that outside of Africa, notably Portugal, Spain, and Greece also experienced shrinkage in wealth per capita due to their extraordinarily high unemployment in the aftermath of the Eurozone Crisis.

The fact is that much of the progress documented in Deaton’s The Great Escape over the past 50 years can be attributed to a single country – China.

Deaton has pointedly observed that we do not yet have all the answers as to how and why so many are left behind, and why the gap between the richest and the poorest is still widening. Deaton’s work shows that advancing inclusive growth remains the foremost challenge of our time.

To advance inclusive growth, we need to address the puzzle of a simultaneous increase in disparity and a decline in poverty. Why are so many people in the world steadily getting ahead while others are being left farther and farther behind? Why do market forces seem to be working well in some places but not so well elsewhere? And why are different countries in the same region (and indeed different regions in the same countries) experiencing dramatically diverse trajectories in economic growth and poverty reduction, often in spite of similar macroeconomic policies, institutions, and regulatory regimes?

This economic growth puzzle has compelled a deep reevaluation of many conventional theories and approaches. And, in so doing, it has stimulated a rethinking of fundamental constructs of economic growth itself. Expert advice on accelerating economic growth over the last 50 years has run the gamut from macro policy prescriptions such as the IMF’s structural adjustment programs to industrial policy for nurturing infant industries and more grassroots-oriented microfinance and direct assistance to the poor plus an emphasis on investment in education and health. The weak results of 50 years of effort have been aptly described by William Easterly, an American economist specializing in economic development, as “the elusive quest for growth” (Easterly, 2002).

Economic Complexity, Productivity, and Economic Growth

At the heart of the puzzle is the challenge of understanding productivity. The standard economic models traditionally treated productivity as somehow “external” to the economic system, something that just happens as a result of technological changes. Before long, however, even the most pig-headed economists came to realize that sound economic analysis is needed to account for technology and productivity. What evolved next is the so-called endogenous growth models that explicitly incorporate technological progress as part of the economic system. There are two main variants:

The first is to tie the rate of technological progress to certain macroeconomic conditions, such as investment in human capital, research and development expenditures, and indicators related to macroeconomic stability and so on.

A second variant focuses on entrepreneurial behavior and conditions under which market competition is intense, which can lead to further creative destruction. While representing a major improvement over their predecessors, the endogenous growth models remain inadequate, being very top-down and they can take us only so far in decoding the dynamics of productivity growth.

In the past decade, advances in a new field of research known as economic complexity, led by Ricardo Hausmann and his team at the Center for International Development at Harvard University in the US, has made it possible to understand better how technology and productivity interact and drive economic development.

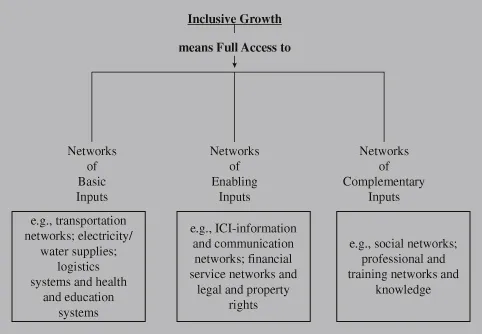

The research on economic complexity highlights a key feature in today’s economic process – the need for economic agents, be they individuals, firms, or even countries, to collaborate in order to be productive. Such collaboration typically takes the form of being connected to a range of vital networks that are powerful enablers for raising productivity. The fact is that modern economic production requires a very large set of complementary inputs (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1. Inclusive Growth, Access and Eliminating Barriers to Inclusion. Source: Hedrick-Wong and Thomas (2018).

At the most basic level, we need to be connected to networks that supply us with clean water and power, and affordable transportation networks that move us efficiently and affordably before we can even participate meaningfully in the economy.

Then there are the critical networks for accessing information and for obtaining important services such as health, education, banking, and finance. There are also the more intangible, but no less critical, social, and professional networks for accessing skills and the know-how that resides in people’s minds. How well an economic agent is connected to these vital networks determines fundamentally how productive it can be.

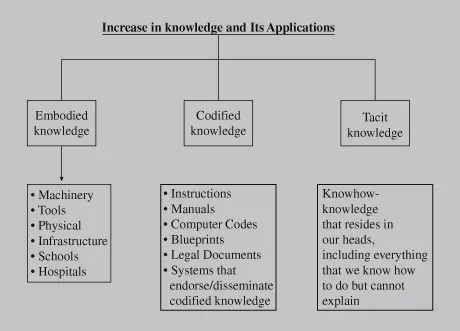

These networks can also be understood as the conduits through which knowledge is transmitted and shared. Depending on the nature of that knowledge, the network characteristics themselves will also differ as will conditions affecting access to these networks.

We can think of knowledge in three different dimensions: embodied knowledge in the form of tools; codified knowledge in the form of information, blueprints, recipes, and manuals; and tacit knowledge, which takes the form of collective know-how (Figure 1.2).

Figure 1.2. Dimensions of Knowledge. Source: Hedrick-Wong and Thomas (2018).

This decomposition of knowledge allows us to examine systematically how, in regard to each of these dimensions at the grass roots level, individuals are able or unable to access the knowledge they need in order to reach their full productive potential (Hausman, Hidalgo, & Bustos, 2013; Hidalgo, 2015). Such an approach in turn opens up a whole new way of thinking about inclusive growth.

In the dimension of embodied knowledge, which includes all tools, machinery, and physical infrastructure, it is easy to see how many people in poor countries are simply not able to access these networks. Simply, there may not be enough of them or they may even be non-existent. For example, in the Sahel region in Africa, rural women spend on average about three hours a day just to fetch enough water for their families to use for the day because their homes are not connected to any form of reliable water supply. They typically have to walk long distances to a source of water and then physically carry the water home. It’s not hard to imagine how much productivity is being reduced daily for these rural women.

A lot of the networks of physical infrastructure are also interdependent: without roads, it is difficult to connect a village to electricity (even allowing for sufficient electricity supply, which is typically not the case) and without electricity all sorts of labor-saving devices and tools will not work. The exclusion from accessing better tools and more efficient infrastructure is a primary reason that the poor are kept at a very low level of productivity. In other words, they are stuck in a poverty trap. A good example is available from Lim’s (2018) PhD research in which he stresses that the lack of access to basic farming and fishing tools is the main cause of poverty in rural communities in Northern Samar in the Philippines.

In the dimension of codified knowledge, which includes essential services such as finance, health care, and public services that are made possible by having effective institutions, many networks for service delivery typically have very high fixed costs and low variable costs. For example, in financial services based on the conventional banking business model, a relatively high fixed cost is incurred in serving a new customer. And the poor being poor, they are unlikely to generate sufficient business volumes to justify the high fixed cost incurred in serving them. So, they are excluded.

Imagine a talented young entrepreneur from a poor rural background in Uganda who has started a very promising small business. His or her customer base is growing rapidly and merits expansion. But lacking family connections and without any significant collateral, the entrepreneur cannot get qualified for any business loans. This exclusion from the network of financial services is why productivity is stuck at a level far below the true potential. One further example of this is the way iCare Benefits, a profit and purpose-driven social enterprise, has enabled the “official or non-casual” workforce in Vietnam to gain access to “no interest” credit to enable women to buy consumer durables in households like refrigerators, washing machines, and smart phones to free up their time to participate in the labor force and use their time more productively.

The third dimension – know-how – is even more problematic. Know-how is everything that we know how to do but cannot explain. Skiing is a know-how. We learn how to ski by skiing not by studying the physics of skiing. A ski instructor cannot download his/her skills directly to a student skier. Consequently, the diffusion of collective know-how is far more difficult than the diffusion of embodied and codified knowledge. Yet more sophisticated and higher value-added economic activities typically require many more inputs in terms of know-how. Lack of access to know-how is a serious constraint of productivity growth and economic development.

Know-how has two properties that make it especially tricky. First, it resides only in people’s brains, not in books of computer codes, so it cannot be downloaded from the Internet. It is a capacity to perform a task that does not involve explicit comprehension. We learn about various know-hows through a long process of imitation – sometimes we work with experienced people and repeat what they do and sometimes we learn from our own mistakes. Second, the growth of know-how in a society is not based mainly on each person knowing more but instead on each person knowing different things. To a large extent, knowledge grows via networks of complementary inputs through increased diversity and by connecting people who know different things.

In modern economic production, the more complicated the task, the more important is the dimension of know-how relative to embodied and codified knowledge. Exclusion from accessing networks of complementary inputs in the form of know-how is therefore particularly detrimental to productivity. Because the networks of complementary inputs in the dimensions of tacit knowledge are made up of people, not machinery or electricity supply, discrimination on the basis of gender, class, caste, region, dialect, religion, and so on can play a big role in suppressing productivity.

From this perspective, the poor are poor precisely because they are stuck in low-productivity activities. In poor countries, workers, micro-entrepreneurs, businesses, and even entire industries are often shackled to low-productivity operations due to the absence of many of the critical conditions that would have enabled workers to learn new skills and get better jobs, micro-entrepreneurs to thrive, small businesses to expand, and bigger firms to finance acquisition of productive assets and to access new and promis...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Title Page

- Chapter 1 Enabling Models of Inclusive Growth from Financial Inclusion to Democratizing Productivity

- Chapter 2 What Is “Financial Inclusion”?

- Chapter 3 How Digital Finance and Fintech Can Improve Financial Inclusion1

- Chapter 4 What Is Social Inclusion and How Financial and Social Inclusion Are Inextricably Linked1

- Chapter 5 Pathways to Inclusive Growth: Social Capital and the Bottom of the Pyramid1

- Chapter 6 The Role of Social Enterprises and Entrepreneurship in Driving Inclusive Growth1

- Chapter 7 The Role of Women Entrepreneurs in Inclusive Growth

- Postscript: Reflections and Future Directions

- Appendix 1

- Appendix 2

- Appendix 3

- Index