This book is available to read until 23rd December, 2025

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Available until 23 Dec |Learn more

About this book

Los Angeles is undergoing a makeover. Leaving behind its image as all freeways and suburbs, sunshine and noir, it is reinventing itself for the twenty-first century as a walkable, pedestrian friendly, ecologically healthy and global urban hotspot of fashion and style, while driving initiatives to rejuvenate its downtown core, public spaces and ethnic neighborhoods. By providing a locational history of Los Angeles fashion and style mythologies through the lens of institutions such as manufacturing, museums and designers and readings of contemporary film, literature and new media, L.A. Chic provides an in-depth analysis of the social changes, urban processes, desires and politics that inform how the good life is being re-imagined in Los Angeles.

Throughout the book, Susan Ingram and Markus Reisenleitner dig up submerged and marginalized elements of the city's cultural history but also tap into the global circuits of urban affect that are being mobilized for promoting L.A. as an example for the global, multi-ethnic city of the future. Engagingly written, highly visual and featuring numerous photographs throughout, L.A. Chic will appeal to any culturally inclined reader with an interest in Los Angeles, its cultural history and modern urban style.

Throughout the book, Susan Ingram and Markus Reisenleitner dig up submerged and marginalized elements of the city's cultural history but also tap into the global circuits of urban affect that are being mobilized for promoting L.A. as an example for the global, multi-ethnic city of the future. Engagingly written, highly visual and featuring numerous photographs throughout, L.A. Chic will appeal to any culturally inclined reader with an interest in Los Angeles, its cultural history and modern urban style.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access L.A. Chic by Susan Ingram,Markus Reisenleitner, Susan Ingram in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Art & Fashion Design. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Chapter 1

Freeway vs Downtown

I drove east on Sunset but I didn’t go home. At La Brea I turned north and swung over to Highland, out over Cahuenga Pass and down on to Ventura Boulevard, past Studio City and Sherman Oaks and Encino. There was nothing lonely about the trip. There never is on that road. Fast boys in stripped-down Fords shot in and out of the traffic streams, missing fenders by a sixteenth of an inch, but somehow always missing them. Tired men in dusty coupes and sedans winced and tightened their grip on the wheel and ploughed on north and west towards home and dinner, an evening with the sports page, the blatting of the radio, the whining of their spoiled children and the gabble of their silly wives. I drove on past the gaudy neons and the false fronts behind them, the sleazy hamburger joints that look like palaces under the colors, the circular drive-ins as gay as circuses with the chipper hard-eyed car-hops, the brilliant counters, and the sweaty greasy kitchens that would have poisoned a toad. Great double trucks rumbled down over Sepulveda from Wilmington and San Pedro and crossed towards the Ridge Route, starting up in low-low from the traffic lights with a growl of lions in the zoo. Behind Encino an occasional light winked from the hills through thick trees. The homes of screen stars. Screen stars, phooey. The veterans of a thousand beds. Hold it, Marlowe, you’re not human tonight.

(R. Chandler 13)

This passage, occasionally left out of abridged versions of Raymond Chandler’s classic 1949 noir thriller The Little Sister, epitomizes the British expat’s bourgeois imaginary of Los Angeles during the 1930s and 1940s, which became inscribed in the genre conventions of noir (Fine 79; Reisenleitner, “L.A. Experience”). Just as Los Angeles was instrumental in defining the American manifestations of noir, so too was the noir genre instrumental in defining Los Angeles in popular culture for the global perception through much of the twentieth century: a city of freeways and suburbs. In the twenty-first century, however, the city has been working hard to change this perception, deliberately confronting and remedying its perceived character as the ultimate suburban nightmare of sprawl around a dangerous and criminalized inner-city, and it has found an effective ally in fashion (Figures 1.1 and 1.2).

At the time of writing this chapter, news about Americans electing Donald Trump as their next president and the immediate reactions in California and Los Angeles, which voted overwhelmingly in favour of Hillary Clinton and issued statements on progress and multiculturalism in response to the right demagogue’s victory (“California Senate Leader to Trump”), completely overshadowed the unprecedented approval of Los Angeles voters, by more than the required two-thirds majority (J. Chandler), of Measure M, a major sales tax increase intended to create the tax base for a significantly improved public transit system. Measure M will

Figure 1.1: Pop-up store in DTLA (photo: S. Ingram).

Figure 1.2: Pavement ornament in the Fashion District (photo: K. Sark).

pay for much-needed sidewalk improvements, pothole repairs, cycling infrastructure, bike share expansion, and a network of greenways […]. To envision how much of a change that Angelenos will see on their streets, Investing in Place notes that up to 8 percent of Measure M’s funds will go towards walking and biking investments, compared to the 1 percent allocated to walking and biking in LA’s current transportation spending.

(A. Walker)

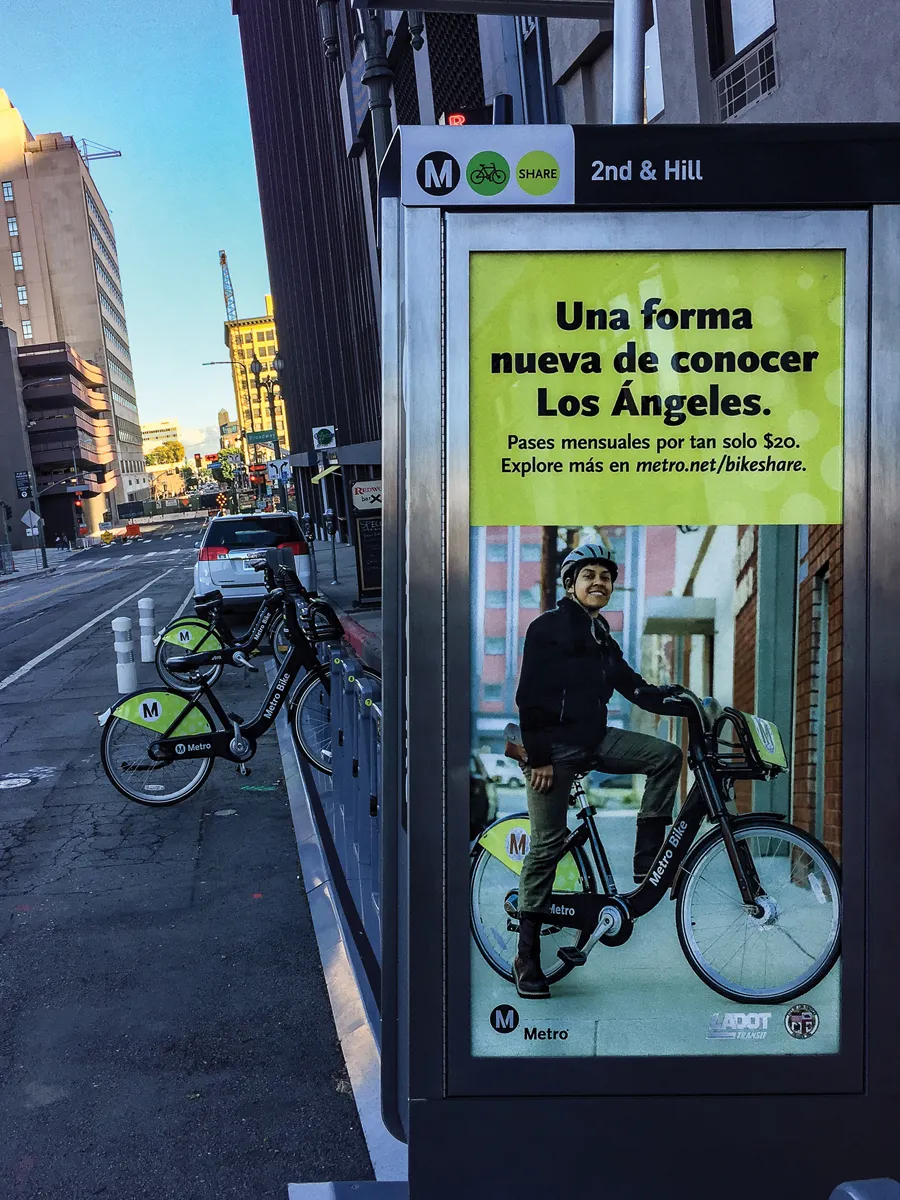

While political events in the wake of the Trump election seem to warrant the fear that “public space is now a more overtly hostile place to people of color, to women, to the LGBTQ community, and to the disabled” (Sulaiman), Angelenos’ endorsement of Measure M counters this fear by supporting Mayor Garcetti’s ongoing efforts (including his backing of Measure M) to re-imagine their city’s streets as walkable, bicycle-friendly, welcoming meeting spaces for the rich diversity that makes up Los Angeles’s inhabitants (Figure 1.3).

In this chapter, we explore some of the re-imagineerings of Los Angeles in the twenty-first century that have challenged the city’s image as an “autopia” and arguably laid the groundwork for the city’s trendiness on the global fashion stage. In the first section, we discuss how these re-imagineerings have been accompanied by struggles over public space, surveillance and gentrification, producing their own subversive reactions. Then we look at three cultural productions that thematize and illustrate the transformations and negotiations of the city’s imaginary from a suburban, noir city of quartz to a rapidly gentrifying centre of millennial creativity: Veronica Mars – The Movie, Naomi Hirahara’s Ellie Rush novels, and Furious 7, which was, at the time of writing, the most recent iteration of the Fast and Furious franchise. These case studies all mobilize genre conventions to expose the relationship between (sometimes conflicting) imaginaries of urban space, community formation, millennial lifestyle and gentrification, surveillance, and the limitations on free movement. The case studies can thus be seen as indicators of a specifically L.A. form of chic, drawing on the city’s histories while negotiating and contesting its transformations.

Figure 1.3: A new way of getting to know Los Angeles (photo: S. Ingram).

From suburban noir to downtown chic

The first comprehensive description of Los Angeles comes from a German cultural geographer, Anton Wagner, who famously explored the city by walking and photographing its neighbourhoods (Wagner, Los Angeles: Werden, Leben und Gestalt):

From August 1932 to February 1933, Wagner covered a swath of the Los Angeles Basin, roughly following the 110 freeway’s north-south trajectory from Pasadena to the Los Angeles Harbor, with jaunts to posh Beverly Hills, the rugged Santa Monica Mountains, and the outlying Pacoima Dam (to which he most likely hitched a ride with friends). A PhD candidate at the University of Kiel in Germany, Wagner took hundreds of photographs to use as research materials for his 1935 dissertation.

(Henderson and Silva)1

Wagner’s magnum opus is often interpreted as indicating that Los Angeles was a walkable city in the 1930s and only developed its sprawl after the Second World War. Such a view is somewhat misleading. Like most major cities in the American West, Los Angeles owes its growth not to the automobile, but to the emergence of transcontinental connectivity provided by the railway. Los Angeles had lobbied hard to be connected to the East Coast and the Midwest, where it drew its population from. The arrival in 1885 of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway’s subsidiary, the Southern Pacific, not only provided the transportation basis for the city’s first spurt of growth through immigration from the Midwest but also influenced the city’s urban/suburban morphology.2 A widespread urban rail system extended the transcontinental rail connections and took care of Angelenos’ transportation needs beyond the city centre. “By 1910, the city boasted impressive streetcar and interurban systems that allowed much of the population to move into suburban developments outside the downtown area” (Bottles 14). Among others, Reyner Banham, best remembered for redeeming the automobile with his adage “I learned to drive in order to read Los Angeles in the original” (Banham, Architecture 5), describes the impact of the railway lucidly and in detail, stressing the particular importance of the Huntington-owned Pacific Electric Railroad, an interurban line whose “Big Red Cars ran all over the Los Angeles area – literally all over” and which “pretty well defines Greater Los Angeles as it is today” (Banham, Architecture 64). Historian Eric Avila is even more explicit in his assessment that

the streetcar takes credit for shaping the distinctive form of the city in its early-twentieth-century incarnation. This brings us to perhaps one of the greatest misunderstandings about the history of Los Angeles: the streetcar and the tracks it rolled upon, not the automobile and the freeway, initiated the decentralized, sprawling pattern of urban growth that amateur historians mistakenly associate with the freeway.

(Avila, “Rethinking the L.A. Freeway” 36)

While the streetcars and interurban rail systems historically laid the foundation of suburbanization (rather than aligning the morphology of Los Angeles with pre-railway East Coast and European cities with historical, walkable centres), the existence and subsequent all but disappearance of public transportation is what the city is now drawing on to create a powerful mythology of, and nostalgia for, streetcars and pedestrian traffic that has been resurrected in recent years to precisely counteract an imaginary of Los Angeles as a city of suburbs (Figure 1.4).

Figure 1.4: Streetcar in The Grove shopping centre (photo: S. Ingram).

On 10 October 2013, Mayor Garcetti, a former visiting professor at the University of Southern California with degrees in Urban Planning and Political Science and at the time just 100 days in office, announced his “Great Streets Initiative”:3

The program focuses on improving street life as the “backbone” for urban planning. In his announcement, Mayor Garcetti reminded us of the walk-friendly history of this great city we all love – a city that was built by the Red Car, designed to encourage walking to transit, and support people of all backgrounds who lived in our communities – until we shifted our priorities to value our cars, how fast we could travel and how conveniently we could park. He plans to return to our roots and transform the main streets of up to 40 neighborhoods into vibrant, pedestrian-friendly destinations.

(lawalks)4

Garcetti tapped into a mythology that places the fault for the disappearance of the fabled streetcars, which supposedly made the city walkable, squarely on the big car manufacturers, an outcome of a widely publicized Senate Judiciary Committee investigation of 1973–74 that revisited, in the environmentally aware and increasingly anti-automobile atmosphere of the 1970s, the late 1940s anti-trust lawsuit against National City Lines (“General Motors Streetcar Conspiracy”).5 The 1974 committee report, authored by Radford Snell,

argued that automobile manufacturers conspired during the forties to destroy a thriving, efficient system of streetcars […] By purchasing controlling interests in urban railways, the corporations replaced electric trolleys with diesel and motor coaches. The inefficiency of the buses in turn led to the demise of a once healthy public transportation network, and left urban residents with the automobile as their only means of transport.

(Bottles 2)

The narrative of a big car companies’ conspiracy against public transportation resonated well with the public and popular culture, probably most famously resulting in Robert Zemeckis’s 1988 blockbuster Who Framed Roger Rabbit. However, Scott Bottles’s revisionist counter-narrative suggests that rather than resulting from a corporate conspiracy, this buyout was a last-minute effort to rescue an already moribund system that had become highly unprofitable (Bottles 240). Angelenos had already adopted the automobile as their preferred mode of transportation in the early decades of the twentieth century, defended car use vigorously and supported campaigns for the creation of improved urban infrastructure for the automobile. Bottles cites the example of Los Angeles City Council’s trying to enact a rigid no-parking law in downtown in 1920 in order to ease congestion (Bottles 15), a measure that had to be rescinded because of an outpouring of pro-auto public affect reminiscent of the smashing of parking meters in Cuba after Castro’s successful revolution in 1959. It was only in the environmentalist atmosphere of ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright

- Contents

- List of Illustrations

- Acknowledgments

- Introduction: L.A. Chic: Between Rags and Riches

- Chapter 1: Freeway vs Downtown

- Chapter 2: Santée Alley vs Santa Fe: Latinidad between Ramonaland and Latino Grit

- Chapter 3: L.A.’s Surf Chic: From Drop-Out Culture to Silicon Beach

- Chapter 4: Bling and the Realities of Compton and Calabasas

- Chapter 5: L.A. Fashion in Museums

- Chapter 6: Los Angelization à la Tom Ford: From American Gigolo to American Apparel

- Conclusion: Learning from Los Angeles, the Josephine Baker of Cities

- Works Cited

- Filmography