6.1 Introduction

At present, a tremendous amount of attention is being focused on finding green alternatives to liquid- or gas-phase catalytic transformations. Ideally, the use of biomass as a feedstock for the chemical industry would be of benefit, and it would be even better if such catalytic transformations could occur on metal-free catalysts. Indeed, sustainable chemistry researchers have been demonstrating a high interest in metal-free catalysis.1

Both the academic and the industrial world are dedicating more attention to finding and improving alternatives to fossil-based carbon sources. The most straightforward candidate, due to its availability, low cost and abundance on Earth, is carbon.2–4 Carbon-based materials are widely used either as supports for metal-based catalysts, or as catalysts themselves.5 Metal-based carbon catalysts are active in the aerobic oxidation of alcohols,6–9 the selective reduction of nitroarene and the oxidative dehydrogenation of ethylbenze,10 among other examples. Returning to carbon as a catalyst, carbon is the ideal candidate because of its position in the periodic table. Diverse bonding states lead to different structural arrangements: sp1-hybridization results in a carbon chain structure, whilst sp2-hybridization leads to a planar carbon structure, and, finally, sp3-hybridization results in a tetrahedral carbon structure. For the target liquid phase reaction, tailoring the physical (surface area and porosity) and chemical (surface functional groups) properties of carbon catalysts is possible through careful and precise synthesis. Sustainable and proficient metal-free carbon catalysts are, therefore, excellent candidates. Corrosion resistance, no heavy metal pollution and environmental friendliness are some of the desired advantages.

Metal-free carbon catalysts, functionalized or not, would, therefore, be able to replace metals or metal-oxide-based catalysts in several reactions, such as hydrogenation and dehydrogenation reactions.11,12 Recent reviews13,14 have reported the use of metal-free carbon materials as catalysts (also called carbocatalysis) for liquid phase reactions. The catalyst design often determines the catalytic performance of these carbon materials. The design of the catalyst is tailored to the target liquid phase reaction (among them dehydrogenation, alcohol oxidation, transesterification, electrocatalysis and photocatalysis). Indeed, the expected catalytic properties of the catalyst suggest how the material surface should be prepared. Thus, the synthesis of these metal-free carbonaceous materials constitutes one of the key elements of a successful reaction. One prerequisite of such a catalyst preparation lies in the total absence of any trace metal elements inside the materials. Only when this condition is satisfied can the catalyst be called a “metal-free carbonaceous material”. The completion of such a condition is difficult, as almost all preparation methods for carbon materials include the use of metal. As an example, carbon nanotubes (CNTs) are obtained by chemical vapor deposition.15 Furthermore, to make these materials active for any reaction, active sites are of importance. The addition of functional groups (heteroatoms) results in a modification of the electronic properties. The insertion of functional groups inside or outside these carbon materials alters the nature (basic or acidic), as well as the physical properties, of the final metal-free carbonaceous materials and, thus, their catalytic performance.

The aim of this chapter is to summarize the main liquid phase reactions carried out with metal-free carbon materials.

6.2 Hydrocarbon Oxidation

The oxidation of hydrocarbons into oxygen-containing compounds to fine chemicals relies upon efficient C–H bond activation. In heterogeneous metal-based catalysis, breaking the C–H bond is possible in the presence of metals.

6.2.1 Cyclohexane Oxidation

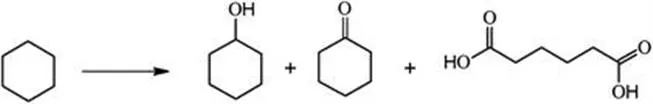

The oxidation of cyclohexane (see Scheme 6.1) is an important industrial reaction, which takes place on a metal catalyst16 or on a bimetallic catalyst.17 The oxidation of cyclohexane results in the production of cyclohexanone, cyclohexanol and adipic acid, which play a significance role in producing nylon polymers.18 The production of cyclohexanone and cyclohexanol is a major process in industrial chemistry, since these two products are chemical precursors for the manufacture of nylon-6 and nylon-6,6 fibres via oxidation to adipic acid.19 Jointly, however, with a cyclohexane conversion and a low selectivity to the target molecule, toxic organic acid waste is produced. Industrially, low cyclohexane conversion is maintained (4–12%) to raise a selectivity over 70% to alcohol and ketones.20

Scheme 6.1 Cyclohexane oxidation to cyclohexanone, cyclohexanol and adipic acid.

It is, therefore, of interest to find a substitute catalyst to fulfil this lack of conversion and selectivity. Some authors have investigated several different catalysts and suggested a series of carbon materials.21 Graphene (sp2-hybridized carbon) oxides, micrometer-sized diamond and nanosized diamond (sp3 bonding configuration) catalyzed the oxidation of the inert cyclohexane to the oxygenated chemicals at a pressure of 1.5 MPa oxygen. Because they contain various structural defects, such as vacancies, the authors also found that non-treated sp2-hybridized carbon materials are more active in the reaction mentioned above. Indeed, sp2 carbon could easily decompose the intermediate molecule C6H11COOH.

With the aim to improve the cyclohexane conversion, some research groups explored the idea of activating the carbon-based materials by doping with N atoms, for example. It is in this respect that Ma et al. utilized N-doped graphene as a catalyst and the cyclohexane oxidation proceeded with 24.7% yield.22 In order to achieve this result, they used oxygen and a small (3.0 mmol) amount of TBHP (tert-butyl hydroperoxide) as oxidants. Moreover, they demonstrated that the amount of N improves the catalytic performance significantly. Wang and co-authors also attributed the improved activity to the presence of graphitic sp2 nitrogen. Although the graphitic sp2 nitrogen is not directly correlated to the catalytic mechanism, it participates in the change of the electronic structure of the adjacent carbon atoms, as well as in the formation of reactive oxygen species.

The selective oxidation of cyclohexane to the organic acid, namely adipic acid, also faces challenges due to low activity and safety problems. Zheng et al. performed this reaction over nitrogen-doped CNTs with a 59.7% selectivity at 45.3% conversion.23 In addition to being active and selective, the catalyst was also stable over five runs.

6.2.2 Ethylbenzene Oxidation

Acetophenone (AcPO) is an intermediate material in the production of perfumes, pharmaceuticals, resins, alcohol, esters, and aldehydes. It can be derived from the selective oxidation of ethylbenzene (EB) (see Scheme 6.2).

Scheme 6.2 Selective oxidation of ethylbenzene to acetophenone.

Several catalysts are active for this reaction, such as MCM-41 molecular sieves with Mn and Co,24 NiAl hydrocalcite,25 and manganese nanocatalysts.26 These three catalysts require the addition of a small amount of TBHP as an oxidant.

However, the main drawbacks of using metallic species or an acidic solvent lie in the costs and the environmental impact. This has aroused more interest in finding a catalyst that can assuage these worries, one that is metal-free, cheap, environmentally friendly, recyclable, efficient and selective in the oxida...