![]()

CHAPTER 1

Introduction to Formaldehyde

1.1 Formaldehyde—The Origins of Life on Earth

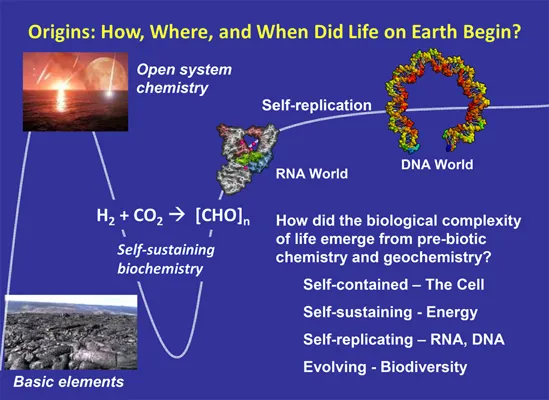

The importance of formaldehyde’s contribution to life must be acknowledged, although this book focuses on toxicities and adverse health impacts of formaldehyde exposure. In recent years, research has indicated that formaldehyde is the likely source of organic carbon solids in the solar system, possibly helping to create organic compounds and molecules that led to life on Earth.1,2 It is well established that RNA preceded DNA and protein enzymes in playing roles in both inheritance and catalysis in the evolution of life.3 This compelling fact begs the question of where RNA originated. What pathways led from prebiotic inorganic chemistry and geochemistry to the biochemistry of life? Figure 1.1 delineates the biochemical conditions and feasible pathways that enabled molecules to cross the frontier from organic chemistry to life. Through open system chemistry, where reactants from different stages of a pathway are allowed to interact, scientists have uncovered early chemical processes that may have led to the emergence of information coding nucleic acids on early Earth.3 These processes were enabled by catalysts that accelerated reaction rates, pruned networks, and developed positive feedback loops. Hence, life was “selected” from a possible universe of small organic molecules, one of which was formaldehyde.

Figure 1.1 Hypothesis for the origins of life on Earth. Reprinted with permission from NSF.4

Formaldehyde is a common molecule throughout the universe.4 Due to its reactivity and abundance, researchers have theorized that interstellar formaldehyde might have had a role in the creation of organic molecules found inside asteroids and comets,5,6 which in turn are suspected to have been responsible for providing early Earth with essential materials such as carbon.7 Most recently, research has shown that organic solids in comets and chondrites were likely derived from a formaldehyde polymer.8 The study concludes: “The origin of a significant fraction of organic solids in primitive solar system objects can logically be attributed to formaldehyde polymerization. Formaldehyde is relatively abundant in the galaxy and also in comets.”8

1.2 Endogenous and Exogenous Formaldehyde

A naturally occurring chemical, formaldehyde can be produced in myriad ways. Endogenous formation arises primarily due to the aldehyde’s role as an important metabolic intermediate that is present in all cells.9 Industrial applications demand the exogenous synthesis of the staple chemical, due to its widespread uses (see Section 1.3 below). In this section, the different ways in which formaldehyde is formed will be discussed.

1.2.1 Endogenous Production of Formaldehyde

In most organisms, including humans, naturally produced formaldehyde is physiologically present as a metabolic byproduct in all bodily fluids, cells, and tissues.10 The endogenous formaldehyde can be produced via numerous sources, including amino acid metabolism, methanol metabolism, lipid peroxidation, and demethylation of DNA, RNA and histone.9,11 Formaldehyde concentrations in human plasma range from 13 to 97 µM.12 The endogenous concentration in the blood of humans, monkeys and rats is approximately 2–3 mg L−1 (100 µM).13,14 Endogenous formaldehyde and its oxidation product, formic acid, are intermediates in the ″one-carbon pool″15 used for the biosynthesis of purines, thymidine, and some amino acids. As a naturally occurring metabolite in many living organisms, formaldehyde is also found at high background levels in many types of food, such as shiitake mushrooms and a variety of seafood. There have also been instances of formaldehyde found in beer, fruit, and vermicelli noodles,16 where it occurs either naturally from an endogenous source or as a result of contamination from exogenous exposure.17 For example, formaldehyde added to chicken feed to prevent birds from contracting salmonella poisoning18 may contaminate the chicken meat and egg. Similarly, endogenous formaldehyde levels in farmed fish may elevate due to the addition of formaldehyde as a preservative.19

Formaldehyde has survived multiple evolutions from natural selection and its ubiquitous presence in all cells inspires the question: what is the key physiological role of formaldehyde? In many instances, it may act as a building block molecule in the production of various biological compounds.20,21 In other cases, formaldehyde may act as a methyl donor through the “one-carbon pool”.22,23 Currently, a novel hypothesis has been proposed that it may act as a second or third messenger in signal transduction pathways,23 which needs to be further explored and confirmed. The full extent of the major physiological role of formaldehyde remains a mystery.

1.2.2 Exogenous Synthesis of Formaldehyde

Formaldehyde has the chemical formula CH2O and is the simplest, yet most reactive, aldehyde.10,24 It has a strong, pungent odor and exists as a colorless gas at room temperature. While Aleksandr Butlerov, a Russian chemist, first synthesized the chemical in 1859, it was August Wilhelm von Hofmann, a German scientist, who identified it in 1867, as the product formed from passing methanol and air over a heated platinum spiral.25

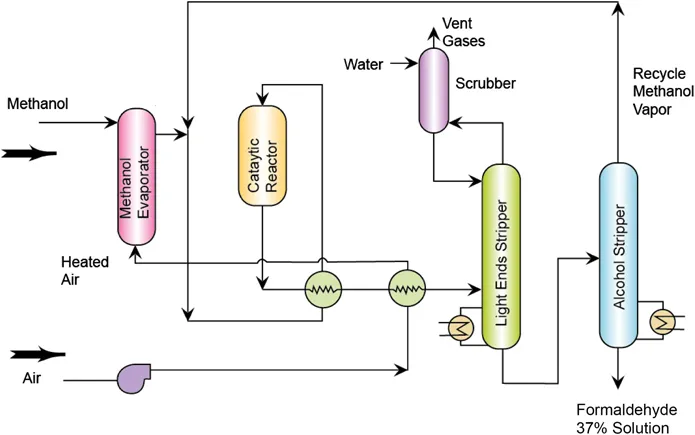

Although there are many possible ways to synthesize formaldehyde, this method is still the basis for the industrial production of formaldehyde today, where methanol is oxidized using a metal catalyst (Figure 1.2). In the dehydrogenation process, the highly endothermic reaction takes place in the presence of iron and chromium oxides. The vapors are absorbed in water, producing formalin in solution. In contrast to the dehydration process, the oxidation process is highly exothermic. Air is heated and sent to a methanol evaporator, where the gases react. The gases are then heated and reacted in the presence of silver and molybdenum oxides. The product gases are sent to a light end stripper and then an alcohol stripper, where formalin is produced. Some unreacted methanol is also recovered and recycled.26

Figure 1.2 Formaldehyde production from methanol and heated air follows two routes: the dehydrogenation and the oxidation process. Reprinted with permission from NPTEL.26

Soon after the technical synthesis of formaldehyde by the dehydrogenation of methanol was achieved, its suitability for numerous industrial applications was discovered. By the early 20th century, an explosion of knowledge in chemistry and physics, coupled with the demand for more innovative synthetic products, set the scene for the birth of a new material—plastic—which dramatically increased formaldehyde usage. Driven by high volume synthetic polymer production, the role of formaldehyde in plastic formation led to it becoming a major industry chemical.

1.3 Industrial Uses of Formaldehyde

Four major types of industrial formaldehyde were developed during the 20th century. Casein formaldehyde, used to make small plastic items such as buttons, buckles, and knitting needles, became popular. It was also critical in the production of phenolic resins, the first completely synthetic plastics, which were made by condensing phenol and formaldehyde in the presence of a catalyst. From the 1920s to the 1940s, phenolic resins—popularly known as “Bakelite,” developed in 1907 by the Belgian-born American inventor, Leo H. Baekeland—were used to make electrical insulators...