- 44 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

This study looks into the role of special economic zones in strengthening the competitiveness of economic corridors in the Greater Mekong Subregion (GMS). It examines factors behind the success of special economic zones and the role they can play in GMS economic corridor development. The analysis is based on a company-level survey in the Mae Sot special economic zone and interviews with clients operating in other zones throughout the GMS. The report offers policy recommendations for GMS ministers on how the zones can contribute toward improving competitiveness of economic corridors and thereby promote economic development.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Role of Special Economic Zones in Improving Effectiveness of Greater Mekong Subregion Economic Corridors by in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business General. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

II. HISTORY OF SPECIAL ECONOMIC ZONES IN THE GREATER MEKONG SUBREGION

SEZs have a long history in some GMS member countries. An early stage in the PRC’s “open door” policy saw the creation of four SEZs in coastal cities in 1980, and since then hundreds of special zones with a variety of titles have been established.

Viet Nam has also been active in creating special zones, and in 2014 reported having a total of 27 border economic zones (ADB 2014, 9), although Aggarwal (2011) and others have observed that some SEZs are inactive.5 By 2015, all GMS countries had embraced SEZs in principle, although it is not always clear how successfully they have been implemented.

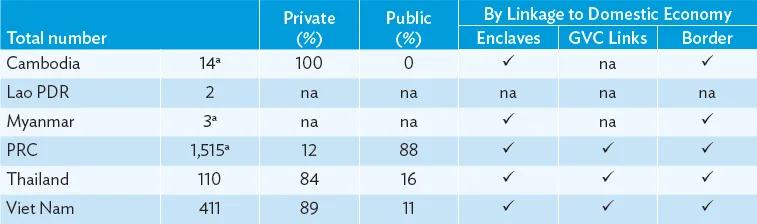

Table 1 summarizes the types of SEZs and their linkages to domestic economies.

Table 1: Types of Special Economic Zones in Greater Mekong Subregion Member Countries

a = Includes public–private partnerships.

na = not available in the source, GVC = global value chain, PRC = People’s Republic of China.

Note: PRC includes all of the PRC, not just the Greater Mekong Subregion.

Source: Asian Development Bank (2015, 71).

In contrast to the longer experience of the PRC and Viet Nam with SEZs, Cambodia, the Lao PDR, and Myanmar only embraced the concept in the 21st century, and Thailand started to promote border SEZs in 2015. The history of SEZs in these latter four GMS countries is described in the next four subsections: Cambodia introduced legislation for SEZ promotion in 2005 (section II.A); the Lao PDR also introduced SEZ legislation in the early 2000s, but implementation has been slower and more uneven than in Cambodia (section II.B); Thailand has successful industrial zones within 100–150 kilometers (km) of Bangkok, e.g., along the eastern seaboard and at Ayutthaya, but only began promoting border SEZs in 2015 (section II.C); and Myanmar has established SEZs, but it is difficult to follow their progress systematically (section II.D). Section II.E describes the situation with respect to SEZs along GMS corridors. The section concludes by noting some issues related to evaluating the success of SEZs.

A. Special Economic Zones in Cambodia

Cambodia established the legal framework for SEZs with a 2005 decree.6 By 2014, 9 SEZs were operating and 20 more had been authorized. Of the nine operational SEZs, three were at Sihanoukville Port (in the GMS Southern Economic Corridor but not at a border); three at Bavet (in the GMS Southern Economic Corridor at the Viet Nam border); and one each in Phnom Penh, Poipet, and Koh Kong (the latter two in the GMS Southern Economic Corridor at the Thai border). In 2014, 67,889 workers, overwhelmingly young women, were employed in the nine SEZs. They differ greatly in size, with 439 factories in the Phnom Penh, Bavet, and Sihanoukville SEZs, but only two in the Poipet O’Neang SEZ and four in Koh Kong. Employment in the two SEZs on the Thai border was 415 workers at Poipet and 988 workers at Koh Kong.

The SEZs are primarily export-processing zones, where firms import almost all their intermediate inputs and sell almost none of their output on the domestic market. This helps to explain the preference for locations near Sihanoukville Port or in the segment of the GMS Southern Economic Corridor from Phnom Penh to Vung Tau deep-sea port. In this context, the Poipet and Koh Kong SEZs are of less interest to producers.

The SEZs are privately owned and managed: the operator is required to have at least 50 hectares (ha) of land and is responsible for roads, electricity, and water supply. The state provides a one-stop service with representatives of all relevant government agencies on site, for which the zone operator pays a fee. Firms locating in an SEZ must first obtain approval; this requires a minimum $500,000 investment in fixed assets, which means that almost all firms in SEZs are foreign owned. Their privileges include guarantees of no price or foreign exchange controls, free remittance of foreign currency, exemption from import duty and value-added tax (VAT), a 20% corporate tax rate, and tax holidays of 9 years for the zone developer and of variable length for other firms. However, these privileges are not necessarily exclusive to firms in SEZs, as firms outside the zones are entitled to apply for the privileges.

In Cambodia, SEZs play a role as enclaves that provide a stable business environment, reasonable infrastructure and public utilities, and less red tape, rather than places where producers respond to tax or other financial incentives. However, implementation is not always as promised. Warr and Menon (2015, 10–11) report complaints from SEZ-based firms that the one-stop service is not one-stop and electricity supply can be unreliable. More recent evidence (e.g., from the firm survey in section IV.B) suggests less dissatisfaction with one-stop services, but ongoing dissatisfaction with infrastructure.7 Implementation is also an issue with respect to tax privileges, e.g., reimbursement of VAT can take a long time (as of June 2016, only one investor had successfully managed to get a VAT reimbursement from the government).

The Cambodian experience illustrates the specificity of SEZs: in this case, they are little more than export-processing zones. The SEZs have been successful in providing jobs that would otherwise probably not exist, but there are virtually no linkages to the domestic economy or opportunities for skill upgrading. Although the SEZs are located along GMS corridors, they are not intended to promote border areas or facilitate trade across borders. The more successful SEZs are simply at points convenient to the nearest deep-sea ports, while border SEZs on GMS corridors (Poipet and Koh Kong) have lagged.

B. Special Economic Zones in the Lao People’s Democratic Republic

In the Lao PDR, the first SEZ decrees date back to 2002–2003.8 However, systematic SEZ legislation lagged behind Cambodia, with the first national steps not taken until 2009–2011. There is uncertainty about how many SEZs exist: although there are more than the two shown in Table 1, only the Savannakhet and Golden Triangle SEZs appear to be active.9

The Savan–Seno SEZ was established in 2002–2003, but there was little activity until after the Second Thai–Lao Friendship Bridge opened in early 2007. The bridge is a key link in the GMS East–West Economic Corridor; and substantially improved connectivity between Savannakhet, the second city of the Lao PDR, and Thailand. For several years after the bridge was opened, activity in the SEZ was largely restricted to a hotel and casino complex. In 2008, a Malaysian company signed an agreement to develop Savan Park as a manufacturing-based SEZ, but development of the infrastructure necessary to attract investors to the park took several years. By March 2016, the Savan–Seno SEZ had 47 licensed investors and appeared to be flourishing.10 Its experience is analyzed in section IV.A.

National legislation for SEZs appears in Chapter 5, Special Economic Zones and Specific Economic Zones, of the 2009 Law on Investment Promotion. Additional clarification is contained in subsequent regulations and decrees, in particular the October 2010 national SEZ decree that led to the establishment in December 2010 of the National Committee for Special Economic Zones in the Prime Minister’s Office; the committee has since been transferred to the Ministry of Planning and Investment. The Asian Development Bank (ADB) provided support in a 2007 technical assistance project that was implemented in 2009–2011, with the aim of encouraging and strengthening local capacities and the country’s overall SEZ regulatory environment.

In an evaluation of the SEZ program and ADB technical support, Lord (2012) gave a lukewarm assessment. He focused almost exclusively on the Savan–Seno SEZ and made negative references to the economic and social consequences of casinos, which could also apply to the Golden Triangle SEZ. However, a few years later, it is clear that the Savan–Seno SEZ is diversifying beyond the casino, which may have even been a positive initial catalyst. This progress is assessed in section IV.A.

C. Special Economic Zones in Myanmar

The legal framework for SEZs in Myanmar is the Myanmar Special Economic Zone Law of 2014.11 The focus has been on Dawei, Thilawa, and Kyaukpyu SEZs, which are all coastal locations, with reference also to potential bord...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Tables, Box, and Maps

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- Executive Summary

- I. Introduction

- II. History of Special Economic Zones in the Greater Mekong Subregion

- III. Case Study: Mae Sot (Tak)

- IV. Effectiveness of Special Economic Zones

- V. Harnessing Special Economic Zones for Border Development

- VI. Conclusion and Policy Recommendations

- References

- Footnotes

- Back Cover