![]()

1

Barry Lyndon and Aesthetic Time

Eternity itself rests in unity, and this image we call time.

Plato, Timaeus

A new relationship to time was the most significant change, and perhaps the defining development, of the French Revolution.

Lynn Hunt, Measuring Time, Making History

When it emphasizes the time in which things take place, their duration, cinema almost allows us to perceive time.

Jacques Aumont, The Image

Upon its US premiere in December of 1975, critics and audiences alike greeted Barry Lyndon with somewhat less fanfare than director Stanley Kubrick had hoped for. Although the film eventually met with modest success in Britain and in Europe, it was, according to Kubrick himself, speaking about his films in 1987, “the only one that did poorly from the studio’s point of view” (Cahill). Adapted from William Makepeace Thackeray’s mid-Victorian novel, The Memoirs of Barry Lyndon, Esq. (1856), the film pairs Ryan O’Neal, a box office darling at the time, and supermodel Marisa Berenson in a fictional tale of an Irish adventurer abroad in Europe in the eighteenth century. At the midpoint of the decade, when Kubrick’s film was released, moviegoers seemed more enamored of films that stridently announced their allegiance to the 1970s, including Dog Day Afternoon, One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Jaws, and Nashville, four titles that were, along with Barry Lyndon, contenders for the best picture Oscar for 1975. Whereas in the previous year, cineastes had been willing to entertain the nostalgic and cynical charm of Roman Polanski’s Chinatown (1974), in this newly post-Watergate, but not yet post-Vietnam, era, they seemed unable to make sense of Kubrick’s mannerist morality play, despite its scathing critique of the global military upheaval known as the Seven Years’ War (1754–63). That pan-European conflagration over empire and dominion prefigured the world wars of the twentieth century. Kubrick’s American audience members—who, if they knew about the war, had learned about it in school, parochially, as the “French and Indian war”—were, apparently, unable or unwilling to make connections between that conflict and the quagmire in Viet Nam.

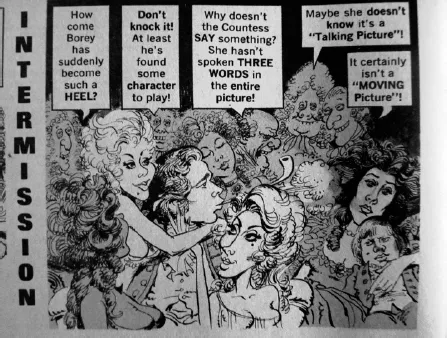

One media source clearly relished the numerous opportunities that Barry Lyndon afforded for critique. Whereas Pauline Kael groused about the “relentless procession of impeccable, museum-piece compositions” (49), the self-styled low-brow magazine named Mad consecrated Kubrick’s epic as a quintessential film of the 1970s in one of Stan Hart and Mort Drucker’s brilliant and anarchic parodies, a spoof entitled Borey Lyndon. As Figure 1.1 makes evident, the movie mavens of Mad indicted the film for its dearth of dialogue and its barely moving images. In their view, Barry Lyndon did not qualify as a film at all.

Figure 1.1 MAD spoof questions the status of “Borey Lyndon” as a moving picture. From MAD #185 copyright E.C. Publications, Inc.

Nominated for two BAFTAs and seven Academy Awards, the film won four Oscars for art direction, cinematography, costume design and music, becoming Kubrick’s most decorated film. Amidst the field of iconoclastic nominees that year, Barry Lyndon lost the Best Picture Oscar to Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, which garnered a total of nine nominations and won five awards. This evidence suggests that the industry recognized and respected the sumptuous spectacle that Kubrick had orchestrated. Oddly enough, however, a critical consensus centered on this highly stylized film’s claim to documentary realism. Prevalent in press accounts was mention of Kubrick and cinematographer John Alcott’s technological acrobatics, which involved retrofitting a camera with a 0.7f Zeiss lens originally created for NASA; the lens was used to film some scenes using only candlelight. This rarefied technological achievement, along with Kubrick’s attention to the details of setting and costumes, was understood by some as serving the goal of “re-creating” the textures and temporalities of a century that no living person had witnessed. TIME magazine critics Martha Duffy and Richard Schickel were not alone when they described the film as a “documentary of eighteenth century manners and morals” (163).

André Bazin, whose observations regarding the relationship between photographic images and reality remain salient well into the digital age, famously made a distinction between directors who put their faith in reality versus those who put their faith in the image (“Evolution” 24). The visual regime of Barry Lyndon makes it abundantly clear that Stanley Kubrick put his faith in the reality of the image. At the same time, his modernist skepticism whittled away at Bazin’s binary construct from both sides. The film’s most apparent conceit is that social relations and aesthetics are mutually determinative, an idea expressed in part through the film’s emphasis on the relationship between eighteenth-century British painting and colonial empire.

For many readers, the name Stanley Kubrick conjures up visions of imagined American futures rather than the somewhat inaccessible past of eighteenth-century Ireland, England, and Europe. His best-known films, including Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb (1964), 2001: A Space Odyssey (1968), and A Clockwork Orange (1971), have shaped more than one generation’s ideas about human progress in the twenty-first century, as anticipated from a vantage point at the middle of the twentieth. No matter how outlandish the technological innovations, linguistic inventions, and fashion sense of Kubrick’s near-future dystopias, his mordant certainty that folly underlies the human will to power remains their animating principle.

In Kubrick’s universe, the past and the future are never very far apart: the unforeseen but inevitable consequences of human action unfold through time as they suddenly, or eventually, attain the status of historical events. Witnessing the mingling of past and future in films such as Dr. Strangelove and A Clockwork Orange may enable some viewers to experience Heidegger’s ekstase (ecstasy)—the feeling of standing outside oneself in time. The uncanny precariousness of that state precludes any sense of comfort with the here and now, however. In fact, the unease associated with the multiple modes of temporality at work in Kubrick’s films gives us cause to question the organization of past, present, and future as successive moments in time.

Despite the strong association between Kubrick and speculative fiction that his iconic works have established, the majority of his films draw upon the quotidian, everyday, milieus of late twentieth-century America. The narratives of Killer’s Kiss (1955), The Killing (1956), Lolita (1962), The Shining (1980), Full Metal Jacket (1987), and Eyes Wide Shut (1999) play out in a present-tense world of America’s urban streets, tourist highways, racetracks, military bases, and moldering grand hotels. Kubrick’s final film, adapted from Arthur Schnitzler’s Traumnovelle, relocates a 1926 story from Vienna to New York’s upper west side in the 1990s, exploring what at the time was called the yuppie lifestyle. The director’s views on the possibility of progress in the span of a single century can be inferred from the fact that the narrative was not revised to mark the temporal shift between the 1920s and the 1990s. Kubrick reportedly felt that relationships between men and women had changed little during that period (Raphael 26–7).

Whether or not Kubrick’s films are firmly situated in the twentieth century, they all question the assumption that humankind as a species has made progress over time. This occurs most strikingly and directly, perhaps, through an engagement with technologies that augur the end of chronological time in Dr. Strangelove and 2001. Stanley Kubrick’s interest in science, both empirical and speculative, is well known. In keeping with the physicists’ concept of T-symmetry—which claims that, at the microscopic level, the laws of physics are invariant under the condition of time reversal—Kubrick’s work often, and sometimes scandalously, implies that the direction of “time’s arrow” might be merely academic and that the difference between moving backward and forward is not always so easy to ascertain.

As texts that trouble human time, Kubrick’s films participate in a rethinking of temporality that D. N. Rodowick associates not only with philosopher Gilles Deleuze’s time-image, but also with a larger postwar project spanning biology and physics. Rodowick writes, “the relation between time and thought is imagined differently in the postwar period, as represented in the signs produced by the time-image no less than by changes in the image of thought in biological sciences and in the image of time introduced by probability physics” (13).

Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon makes time by engaging with ideas about the passage of time. From even before its initial release, the film was subjected to a discourse concerned with problems of time: its production period was seen as excessive, its running time prodigious, and its generic pedigree as a costume drama outdated. Not surprisingly, perhaps, the film has been marked by this emphasis, although detailed analyses of the film tend to focus on its spatial attributes and its formal beauty.

In some ways, the film has been cast as a victim of its time. Barry Lyndon has been seen as disadvantaged by the decade of its release—the 1970s—and also by its running time of 184 minutes. Not a bawdy picaresque in the vein of Tom Jones (Richardson 1963), a film to which it is often compared, Barry Lyndon is a stately drama released at the midpoint of a decade whose cinema has become celebrated primarily for gritty realism, rapid editing, and showy camera techniques. In point of fact, a number of films of remarkable length were made during the 1970s, including Ryan’s Daughter (Lean 1970) at 195 minutes; The Godfather (Coppola 1972) and The Godfather, Part II (Coppola 1974) at 175 and 200 minutes, respectively; Scenes From a Marriage (Bergman 1973) at 167 minutes; Nashville (Altman 1975) at 159 min; 1900 (Bertolucci 1976) at 345 minutes; and Berlin Alexanderplatz (Fassbinder 1980) at 931 minutes.

A number of these directors have been retroactively designated the progenitors of “slow cinema,” a development within the international cinema of the 1990s and 2000s that Jonathan Romney associates with the work of Béla Tarr, Aleksandr Sokurov, Hou Hsiao-hsien, Pedro Costa, Apichatpong Weerasethakul, and Albert Serra (“Are you sitting”). In his 2003 address to the 46th San Francisco International Film Festival, Michel Ciment constructs a historical trajectory for this “cinema of slowness, of contemplation,” and specifically mentions Barry Lyndon as part of a group of “antidote films” that rejected the rapid pace of Hollywood films made in the 1960s (“The State”). Ciment asserts Kubrick’s bona fides as both a technologist and a contemplative artist, as if the two temperaments were incompatible, and as if an interest in technology presupposes a desire for speed: “Kubrick, himself a master of technology, has produced antidote films such as 2001: A Space Odyssey, Barry Lyndon, and Eyes Wide Shut, with their provocative slowness” (“The State”). Slow films exhibit an “intrepid and rigorous formal invention” (“Are you sitting”) in Jonathan Romney’s view and “downplay event in favor of mood, evocativeness and an intensified sense of temporality” (“In Search” 43). In these films, in contrast to a contemporary American cinema that has “lost interest in awe and mystery,” Romney finds, “the spiritual is at least a potential force” (“In Search” 43). These claims do not merely apply to contemporary cinema; they also appropriately describe Barry Lyndon.

Despite Ciment’s remarks about Barry Lyndon, Kubrick’s film rarely surfaced amidst the lively polemic that developed within cinema studies around the pleasures of the protracted pace. After Sight and Sound, editor Nick James indicated that he appreciated “the best films of this kind,” but considered slow films to be “passive-aggressive, in that they demand great swathes of our precious time to achieve quite fleeting and slender aesthetic and political effects” (5), blogger Harry Tuttle lambasted James in Unspoken Cinema (“Slow films”). Tuttle’s broadside, in turn, elicited a response from Steven Shaviro, who compared the contemplative cinema of the 2000s to that of the 1970s and found it lacking. Shaviro considered the twenty-first century crop of slow films “nostalgic and regressive” because they “give older cinematic styles [. . .] a new zombiefied life in death” (“Slow cinema versus fast films”).

At the time of its release, and in the years since, Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon has been subjected to similar criticisms. In both commercial and scholarly terms, the film never fully recovered from doubts expressed by the public, the critics, and the academic philosophers. The mixed critical and popular response to the film was not unusual for Kubrick’s work, as Thomas Elsaesser has eloquently noted, writing that Kubrick’s films generally “me[et] with indifference and incomprehension, and, only later, with hindsight, [reveal] their place in a given generic history” (140). Whereas Judith Crist praised Barry Lyndon’s beauty in The Saturday Review (61) and TIME’s Duffy and Schickel called it an “art-film spectacle” (160), The New Yorker’s Pauline Kael resisted the film’s static compositions and apparent commitment to historicism, seemingly annoyed by the film’s “refusal to entertain us, or even to involve us” (52). Her views were echoed humorously in the MAD parody discussed earlier, which itself suggested that the film was an emblem of high culture seriousness and thus, implicitly, nostalgic, regressive, and deserving of mockery. Through my examination of modes of temporality in Barry Lyndon, I hope to reconsider some of the charges leveled against the film, and particularly, that it is boring and hermetic, in light of recent characterizations of slow cinema as a contemplative form. In its slowness, and its attentiveness to diverse temporal modes more generally, the film affords viewers opportunities for verbal and visual as well as for emotional and intellectual engagement.

Moving from the low culture of MAD and popular film criticism to high theory, I turn to Fredric Jameson and Jean Baudrillard, who weighed in with critiques that foreground Barry Lyndon’s formal beauty and yet also implicitly consider the film’s relationship to (its own) time. Jameson writes about Barry Lyndon only in the context of Kubrick’s subsequent film, The Shining, thus framing his discussion within a relationship of sequence and succession, and treats the former work as an exemplar of the historical crisis within postmodernism. He suspects that Barry Lyndon’s “very perfection as a pastiche intensifies our nagging doubts as to the gratuitous nature of the whole enterprise” (“Historicism” 92). In making reference to pastiche, the textual juxtaposition of historical references unencumbered by critical judgment, Jameson relegates the film to the status of an empty imitation, a technically proficient copy. Baudrillard also complains about Barry Lyndon’s cold perfection: without “a single error,” he writes, the film simulates rather than evokes (45). Its “very perfection is disquieting” (45). As it does for Jameson, Barry Lyndon, for Baudrillard, stands for an entire generation of cultural production: it represents “an era of films that in themselves no longer have meaning strictly speaking” (46). Reexamining Barry Lyndon through an analysis of its modes of temporality calls attention to the way that the perceptions of the film’s “perfection,” its surface beauty, and its obsolescence are historical artifacts themselves. I would argue that Kubrick’s film generates meaning precisely through parody—with an irony that exposes the politics underlying practices of visual culture within modernity.

Not surprisingly, given the challenges it posed to American cinema-goers of the 1970s, Kubrick’s magnum opus “failed in the laboratory of commerce” as Thomas Doherty delicately puts it (B10). “Demanding and uncommercial” in the eyes of Robert Kolker (6), Barry Lyndon proved to be Kubrick’s least lucrative cinematic endeavor, grossing only $20 million in the United States against a production budget of $11 million; in comparison, Cuckoo’s Nest took in $112 million with a budget of just over $4 million (IMDb.com).

Over the course of three decades, which included a rerelease in 1977, Barry Lyndon was rarely screened in the United States and descended into obscurity. In Stanley Kubrick Companion, James Howard observes “Barry Lyndon rivals A Clockwork Orange as the least visible of the director’s works” (143). This is actually saying a great deal, as Kubrick asked Warner Brothers to withdraw A Clockwork Orange from circulation in the United Kingdom in the early 1970s after controversies arose involving supposed copycat crimes. In The Complete Kubrick, David Hughes underscores the extent of the critical and popular neglect of Barry Lyndon: