![]()

1

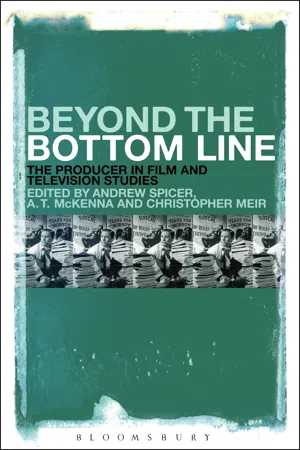

Introduction

Andrew Spicer, A.T. McKenna and Christopher Meir

The financial side of art has always proved problematic for academics and critics alike, as if fetish objects are somehow sullied by the profit motive. With the producer being so closely associated with bottom-line concerns, this apparent distaste for money matters within the academy could go some way to explaining the producer’s relative absence from Screen Studies literature. However, although scholarly work on producers is remarkably sparse compared to, say, work on directors, depictions of producers in popular culture are plentiful. The producer, then, is not an unappealing figure. As a regular feature of movies, novels, cartoons, legends and anecdotes, the producer is often caricatured, but usually with a degree of affection. Nonetheless, while the grubbiness of bottom-line concerns may be attractive in tall tales and lampoon, they are still not adequately addressed by scholarship which often fallaciously dichotomizes art and finance. The producer, then, such an essential component of any production, remains a largely misunderstood and under-analysed figure.

It is not the purpose of this collection to romanticize the producer still further, nor is it merely to explode myths. Our purpose is to understand the role of the producer or, more precisely, the roles of the producers. The producer can define studios, genres, even national cinemas, but will also bring the artistic expressions of limited appeal from auteurs or boutique collectives to a screen. Given that the ‘role’ of the producer may comprise many different roles, in order to better understand producers, we feel that an edited collection, gathering together a range of different approaches and perspectives, is the ideal format to address this topic. Recent years have seen an increasing number of academic articles and monographs devoted to producers, yet this is the first collection devoted to the subject. Because this collection incorporates a wide variety of approaches and contexts, it is, we feel, a timely addition to this growing field of study. Moreover, this collection demonstrates how, by analysing the producer, these approaches and contexts can provide deeper insights into several of the dominant debates within Screen Studies, including those pertaining to authorship, creativity, media historiography, national and transnational media cultures as well as many others.

The producer is easy to caricature but the role is difficult to define. In the 1970s, Gore Vidal observed, ‘It is curious … how entirely the idea of the working producer has vanished. He is no longer remembered except as the butt of familiar stories: fragile artist treated cruelly by insensitive cigar smoking producer.’1 This volume seeks to remedy that ‘vanishing’, but first we must deal with the caricature identified by Vidal because it is so potent in the popular imagination. To this end, the first section of this Introduction, ‘Unreliable histories and self-made scapegoats’, provides a short historiographical account of the development of the familiar cliché of the producer and how this has contributed to their undervaluation. The second section, ‘Media industry studies’, places the producer within the broader field of media production studies and directly addresses the idea of the working producer through a broad definition of this most mysterious of roles. The third and final section, ‘Contributors and contexts’, provides a summary account of all chapters that comprise this volume, places them within wider academic discourse, and suggests some productive avenues for future work.

For this first edited collection of work devoted to the producer, we sought contributions with a wide variety of approaches and contexts in order that the reader has a rich resource to deepen their understanding of the producers’ role. Given that much of the work published on producers in recent years has focused on Hollywood, we have deliberately chosen to downplay this field of study to provide an internationalist and pan-historical volume. Nonetheless, to address fully the enduring stereotype of the producer in a historiographical sense, it is to Hollywood that we must first journey.

Unreliable histories and self-made scapegoats

To find the root of Gore Vidal’s familiar stories, the producer as cigar-smoking tyrant, we must look to Irving Thalberg. In 1922, Thalberg fired director Erich von Stroheim from Merry-Go-Round. It was a David and Goliath struggle, with the producer, not the director, in the David role. Thalberg had tried to fire von Stroheim from projects before but von Stroheim’s starring roles in the films he directed made it impossible. However, von Stroheim’s duties on Merry-Go-Round were entirely behind the camera and this made his dismissal less difficult, albeit, not easy. Thalberg, studio manager of Universal and barely 23 years old, went into battle with one of the most powerful directors in Hollywood and, by doing so, cemented his own reputation and made Hollywood movies a producers’ medium for its Golden Age.2 Producer power in the studio system was personified by Thalberg, a slight, slim non-smoker; the big cigar, the big desk and the big belly of caricature came later. The caricature came about as a result of many forces, including social, intellectual and cultural prejudices, but also from movies, the film industry and producers themselves (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1 Portrait of Irving Thalberg in the 1920s. Courtesy of Photofest

Thalberg was the inspiration for Munro Stahr, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s protagonist of The Last Tycoon, the mercurial genius who understood ‘the whole equation’ of movie-making. To understand an equation, it is useful to break it down into its component parts. In an ideal world, a capacity for compartmentalization allows the producer to be the overseer. They are the first in and the last out, and will maintain overall control of a project and carry the burden of ‘real world’ administrative and financial concerns. In performing this role, the producer creates space for the component creative personnel to focus on and fulfil their task more effectively. Michael Klinger, for example, once engaged in a lengthy correspondence to acquire rights to René Magritte’s L’Assassin Menace, so that Mike Hodges could use the image for a fraction of a second in Pulp (1972).3

In a more cynical world, the producer is duplicitous, if not multiplicitous. This producer confines operatives to their component part, and so controls perception and restricts access to the ‘whole equation’. The duplicitous producer profits from atomization of personnel and maintains overall control of ‘real world’ concerns such as money. Joseph E. Levine, for example, once summoned Mel Brooks into his office and explained, ‘Mel, my job is to get the money for you to make the movie. Your job is to make the movie. My job is to steal the money from you. And your job is to find out how I do it.’4

Both idealist and cynical views of the producer have been true at different times, at the same time, and in the same person. Importantly, in both these anecdotes it is the producer who appears more capable, more competent and more adept at understanding the world than the sheltered director. A reductive analysis, perhaps, but it is one that informs producer historiography. To return to Vidal, it is not only the cruel producer that informs the familiar stories, but also the fragile artist. The dichotomy between art and commerce may be fallacious, but it is a stalwart of many of the portrayals that inform popular understanding of the producer.

In 1941, Hollywood produced one of the most widely quoted and best loved lampoons of film bosses in Sullivan’s Travels, with its famous scene of studio money men repeatedly demanding assurances that successful but disillusioned screenwriter John Sullivan’s proposed picture about the sufferings of the average man will have ‘a little sex in it’. The producers try to convince Sullivan to stick with the escapist comedies that have proved so popular, and made ‘a fortune’, but Sullivan wants to make O Brother Where Art Thou? a ‘commentary on modern conditions. Stark realism. The problems that confront the average man … a canvas of the suffering of humanity!’ As he pitches his movie to the studio executives, it becomes clear that Sullivan’s background is one of wealth and privilege, while the studio men come from poverty and hardship. This realization causes Sullivan, crestfallen, to crumple into a chair and berate himself for having the temerity to imagine he could hope to understand the wider world. In pitching pecuniary street wisdom against artistic idealism, this deftly constructed routine finds a parallel in Leo C. Rosten’s observations of the studio system. Noting the widespread prejudice against Hollywood’s nouveau riche in the 1940s, Rosten suggests:

When the name of a movie magnate is uttered, one of the first associations to spring into the mind of the listener is ‘tailor’ or ‘button-hole maker.’ The implicit assumption … is that ...