![]()

1

Propaganda in the New State: The May Revolution (A Revolução de Maio)1

Propaganda in Portuguese cinema

Salazar frequently described the New State as an apolitical regime. He blamed the excess of political activity during the First Republic for the socio-economic chaos that he encountered when he began to govern: “For many years in this country, politics killed administration: partisan fighting, revolutions, intrigues, […] power for power’s sake have proved to be irreconcilable with the resolution of many national problems.”2 Salazarism responded to this impasse with a “politics without politics” or, even better, a “Government without politics” that “seemed like madness to many and was a blessing for all.”3 In many of his speeches, the statesman criticized the “democratic disorder”4 motivated by the “absolute sterility of politics considered as an end in itself.”5 He asserted that any multi-party system would unavoidably include lies and mistakes, in so far as each party proclaims that its doctrines are true, but they cannot all be equally valid, given their disparate and sometimes contradictory assertions.6 Salazar’s negative verdict regarding the feasibility of democracy is based on a conception of truth as universal. The democratic system placed this notion in doubt through trivial disputes among political parties, and as a result led to the nation’s decline.7 According to Salazar, “politics”—a term that in his vocabulary was synonymous with democracy’s vices—should therefore be replaced with an authoritarian regime grounded in immutable truths.

Salazar claimed that truth was the root of all his governmental decisions: “Like social life, politics and public administration should be based on truth: by temperament, by conviction, by an imposition of conscience, I advocate this way of directing and administering.”8 Salazar’s administration was founded upon the belief that “political truths”9 exist and are as real as scientific laws. The “politics of truth” that Salazar proposed contrasted with the “politics of lies and secrets” of the Republican government that preceded the New State.10 For the head of government, truth was indisputable, just like other equally eternal values such as the Good or Beauty: “We believe that Truth, Justice, Beauty, and the Good exist; we believe that individuals and nations rise up through the worship of these values, they become noble, become dignified […].”11 These qualities, which resemble Platonic ideas in their metaphysical immateriality, are considered so evident that they do not require explications or justifications.

José Gil points out that Salazar developed a “rhetoric without rhetoric”12 in his speeches, since the veracity of his statements should be so clear to the audience that any persuasive rhetorical device became unnecessary.13 This discursive simplicity is not overlooked by French journalist Christine Garnier, who reports that “[t]he President, in fact, never endeavored to please the masses. Few words.”14 Thus, when Salazar identified God, Fatherland, Authority, Family and Work as the pillars of his government, he emphasized at the same time that these “great truths” should not be questioned.15 Rather, Salazar’s core values, with their indisputable legitimacy, became a panacea for the crisis that the country traversed—a situation that, in turn, could only be overcome through a limitless trust in these principles. Therefore, Salazar postulated the existence of an apodictic, eternal truth that he established as a measure of all political activity and social structures.16 Respect for this truth would lead to the Good or, in other words, to a stable and prosperous society.

Although he emphasized that truth is obvious, Salazar admitted that its clarity may be muddled by misrepresentations or abusive interpretations. He considered it the duty of any political regime to inform and guide the public down the path of truth. Within the New State, this task fell to propaganda:

Some, still, consider propaganda as a subtle instrument that, gathering all of the contributions of science and art […] changes colors, disfigures the facts […] creates a truth, so clear, so incisive, so evident that everyone will judge it as genuine. […] this is not what propaganda means to us. / What is it, then? Whenever I spoke of this subject I always linked propaganda to the political education of the Portuguese people, and I assigned it two functions: first information, then political education.17

Salazar rejected the notion that propaganda produces a tendentious version of events, and instead he deemed it to be a means of information and political education.18 As he said in a speech given during the inauguration ceremony of the Secretariat of National Propaganda (SPN), political realities do not correspond to facts, but to the information that the public has access to: “In truth, however, as far as politics is concerned, all that appears to exist, actually exists. I mean to say, lies, fictions, fears, even if they are not justified, create spiritual states that are political realities: we must govern based upon these, with them, and against them.”19 An imbalance between reality and the perception that society has of it sometimes arises, and the role of propaganda is to bridge this gap in order to disseminate the truth. Salazar was careful to distinguish his version of propaganda from the propaganda practices of other totalitarian states of the 1930s, underscoring the need to “disregard identical services in other countries,” and to avoid “the exalted nationalisms that dominate them”—probably referring here to the propaganda services of Mussolini’s Italy and Nazi Germany.20 This is consistent with his definition of propaganda as the transmission of the truth, which, since it is evident, does not need artful embellishments.

In the already mentioned speech given for the inauguration of the SPN, Salazar stated that the Institution’s main goal would be combatting “error, lies, slander or simple ignorance, from within or abroad” under the banner of truth and justice.21 Even though a part of Portuguese propaganda was geared towards improving the image of Salazarism abroad via the translation of works about the government’s politics, the participation in international exhibitions, and the dissemination of images that highlighted the country’s natural beauty or historical sites, the majority of the SPN’s resources were channeled to internal matters.22 Some of its functions included control of the press and coordination of censorship services, organization of pro-government demonstrations, and financing of artistic projects. Cinema also fell within the scope of the SPN’s intervention, and the institution financed numerous documentary shorts.23 It also gave subsidies for the production of feature-length films, the majority of which focused on topics related to national history and popular culture.

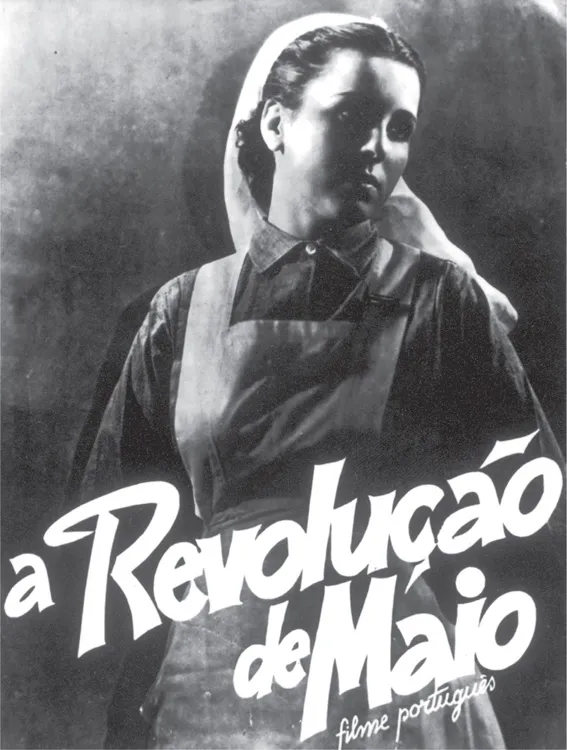

The film The May Revolution (A Revolução de Maio, 1937) was the only fictional feature-length film produced entirely by the SPN. This movie was created to celebrate the tenth anniversary of the 28 May 1926 Revolution that later led to the creation of the New State. It was directed by António Lopes Ribeiro,24 one of the personalities in cinema at the time who most openly supported the ideology of the New State, for which he received the epithet of “Salazarism’s official filmmaker.”25 Lopes Ribeiro was also responsible for various other films with a propagandistic slant, such as the fictional feature-length Spell of the Empire (Feitiço do Império, 1940), which we will analyze later, and documentaries about landmark events for the regime, such as presidential trips to the colonies, the bicentennial celebrations of 1940, and the inauguration of the National Stadium in 1944.26

The plot of The May Revolution openly discusses a political topic, namely the threat that communism posed to Salazar’s regime. It is virtually the only example of an explicitly political fiction film during the first decades of the New State. Furthermore, the movie stands out for its inclusion of documentary footage in the fictional plot, a technique that Lopes Ribeiro also used in Spell of the Empire. The May Revolution translates Salazar’s notion that the values of the regime were necessarily good and just into cinematographic language, deploying propaganda to inform the public about the truths underlying New State ideology. However, the film also shows that there was not always a peaceful coexistence of differing ideas about propaganda and truth within the regime.

The May Revolution seeks to establish an affective bond between Salazar and the people through the juxtaposition of fictional images with documentary sequences of the statesman being applauded by the multitude, thereby diluting the border between real events and the plot. The goal of this fusion of documentary and fiction is to transform reality itself, using the persuasive power of art to reshape the boundaries of the real. Propaganda is then no longer a mere reproduction of facts, as Salazar intended, since it becomes a method of influencing and even reconfiguring actuality.

Art’s role as an ideal model of socio-political reality was the subject of a thesis defended by António Ferro. A modernist intellectual and the director of the SPN from its creation until 1949, Ferro collaborated with Lopes Ribeiro as co-author of the film’s screenplay.27 For Ferro, the existence of a close relationship between the leader and the people was vital for the regime, and art, especially cinema, was the most efficient way to promote this link. Propaganda films like The May Revolution should not simply show eternal truths, but rather create their own truths, making it the Portuguese people’s responsibility to put this artistic blueprint into practice in their daily lives.

Salazar’s truth as ideology

The cinema of the New State systematically employed the topos of “conversion” in its attempt to win over the viewers’ support for the regime’s politics, as the historian Luís Reis Torgal emphasizes in his article about Salazarist cinematographic propaganda.28 The narrative of The May Revolution is no exception to the rule, in that it follows the transformation of the protagonist, César Valente (António Martinez), from a supporter of communism to a staunch believer in Salazarism. Several factors contribute to this transformation, among them his romantic involvement with a young girl, Maria (Maria Clara), whose father died while defending the regime. Yet, the main cause of the protagonist’s “conversion” lies in his discovery that the country progressed considerably during the years he was away from Portugal, which coincided with the first decade of the New State.

One of the first steps toward César’s transformation occurs when he visits the National Institute of Statistics. The sequence begins with a medium-long shot, filmed from a slightly high angle, in which the protagonist is alone in the middle of an enormous plaza facing a majestic staircase, surrounded by newly...