![]()

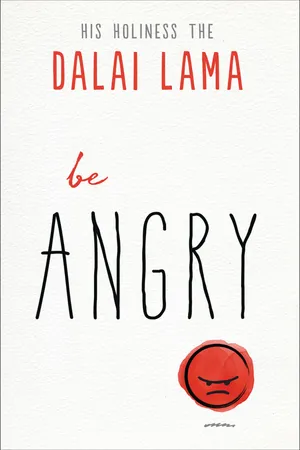

ANGER

In the real world, exploitation exists, and there is a great and unjust gap between rich and poor. The question is, from a Buddhist perspective, how should we deal with inequality and social injustice? Is it un-Buddhist to feel anger and indignation in the midst of such circumstances?

This is an interesting question. Let's begin by looking at the matter first from a secular point of view—education. What do we teach about anger?

I often say we should have more serious discussion and research about whether or not our so-called modern education system is adequate enough to develop a healthier society.

Some American scientists I know are seriously concerned about social problems. Over the years, we have had many discussions about the value of compassion, and several of these scientists conducted an experiment with university students.

For a period of two to three weeks, they had the students practice attentive, deliberate meditation (mindfulness), and after the two or three weeks of meditation, the scientists investigated what changes had taken place in their subjects. They reported that after this period of meditation practice, the students became calmer, had greater mental acuity and less stress, and had increased power of memory.

The University of British Columbia in Canada has created a new institution that is conducting research on how to cultivate warmheartedness in students within the modern educational system. At least four or five universities in the United States are acknowledging that modern education lacks something in this regard.

Research is finally being conducted to address this problem and propose ways to improve the system.

Unless there is a worldwide movement to improve education and give more attention to ethics, this work will take a very long time, and it will be very difficult.

Of course, in Russia and China the same dangers exist, and in India, too. India may be a little better off because of its heritage of traditional spiritual values, even if they probably do not think about this question in terms of logic or reason.

Japan is a modernized country and therefore Westernized, so Western problems are also occurring in Japan. With the adoption of a modern educational system, traditional values and family values have suffered. In the West, the power of the Church and its support for the family has declined, and society has suffered the consequences. In Japan, too, the influence of religious institutions has faded, and with it, families have suffered.

Now let's talk about what role religious people can play in solving social problems. All religious institutions have the same basic values—compassion, love, forgiveness, tolerance. They express and cultivate these values in different ways. And religions that accept the existence of God take a different approach from those, like Buddhism, that don't. The current pope is a very sophisticated theologian, and though he is a religious leader, he emphasizes that faith and reason must coexist.

Religion based on faith alone can end up as mysticism, but reason gives faith a foundation and makes it relevant in daily life.

In Buddhism, from the start, faith and reason must always go together. Without reason, it is just blind faith, which the Buddha rejected. Our faith must be based on the Buddha's teachings.

The Buddha first taught the Four Noble Truths, the basis of all Buddhist doctrine, according to which the law of cause and effect governs all things.

He rejected the idea of a god as creator of all things. Buddhism begins with the logical understanding that all happiness and suffering arises from specific causes. So Buddhism is rational from the start, particularly the schools of Buddhism based on the Sanskrit tradition, including Japanese Buddhism—that is, the Buddhism that carries on the great Nalanda University tradition from ancient India.

“BUDDHISM BEGINS WITH THE LOGICAL

UNDERSTANDING THAT ALL HAPPINESS

AND SUFFERING ARISES FROM

SPECIFIC CAUSES.”

According to the Nalanda tradition, everything should be understood according to reason. We must first be skeptical and doubt everything, as we do in the modern world. Skepticism produces questions, questions lead to investigation, and investigation and experimentation bring answers.

Buddhists do not believe the teachings of the Buddha merely because he expounded them. We approach the teachings with a skeptical attitude, and then we investigate whether they are true. Once we know that a teaching is truly correct, then we can accept it.

Buddhist teachings are not mere mysticism; they are based on reason.

Japanese Buddhism has diverged considerably from that reason-based approach. For example, in Zen Buddhism, the goal is to transcend verbal logic. In the Nembutsu faith [of the Pure Land sects], the goal is to entrust ourselves completely to the saving power of Amida Buddha.

“SKEPTICISM PRODUCES

QUESTIONS, QUESTIONS LEAD TO

INVESTIGATION, AND INVESTIGATION

AND EXPERIMENTATION

BRING ANSWERS.”

Because Japanese Buddhists emphasize transcending logic and surrendering oneself, they tend to say that logical statements are not really Buddhist and assume that people who think in a logical way have achieved only a low level of Buddhist understanding or have not yet completely surrendered themselves.

When these Buddhists say things like, “Don't confuse yourself with logic. Just have faith,” that gives monks an excuse to stop investigating their own experi...