- 512 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

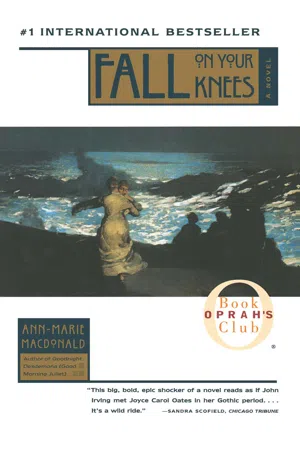

Fall On Your Knees

About this book

The Piper family is steeped in secrets, lies, and unspoken truths. At the eye of the storm is one secret that threatens to shake their lives -- even destroy them.Set on stormy Cape Breton Island off Nova Scotia, Fall on Your Knees is an internationally acclaimed multigenerational saga that chronicles the lives of four unforgettable sisters. Theirs is a world filled with driving ambition, inescapable family bonds, and forbidden love.Compellingly written, by turns menacingly dark and hilariously funny, this is an epic tale of five generations of sin, guilt, and redemption.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

Book 1

THE GARDEN

To Seek His Fortune

A long time ago, before you were born, there lived a family called Piper on Cape Breton Island. The daddy, James Piper, managed to stay out of the coal mines most of his life, for it had been his mother’s great fear that he would grow up and enter the pit. She had taught him to read the classics, to play piano and to expect something finer in spite of everything. And that was what James wanted for his own children.

James’s mother came from Wreck Cove, the daughter of a prosperous boat builder. James’s father was a penniless shoemaker from Port Hood. James’s father fell in love with James’s mother while measuring her feet. He promised her father he wouldn’t take her far from home. He married her and took her to Egypt and that’s where James was born. Egypt was a lonely place way on the other side of the island, in Inverness County, and James never even had a brother or sister to play with. James’s father traded his iron last for a tin pan, but no one then or since ever heard of a Cape Breton gold rush.

It used to make his father angry when James and his mother spoke Gaelic together, for his father spoke only English. Gaelic was James’s mother tongue. English always felt flat and harsh, like daylight after night-fishing, but his mother made sure he was proficient as a little prince, for they were part of the British Empire and he had his way to make.

One morning, the day before his fifteenth birthday, James awoke with the realization that he could hit his father back. But when he came downstairs that day, his father was gone and his mother’s piano had been quietly dismantled in the night. James spent six months putting it back together again. That was how he became a piano tuner.

All James wanted at fifteen was to belt his father once. All he wanted at fifteen and a half was to hear his mother play the piano once more, but she was dead of a dead baby before he finished the job. James took a tartan blanket she’d woven, and the good books she had taught him to read, and tucked them into the saddlebag of the old pit pony. He came back in, sat down at the piano and plunged into “Moonlight Sonata.” Stopped after four bars, got up, adjusted C sharp, sat down and swayed to the opening of “The Venetian Boat Song.” Satisfied, he stopped after five bars, took the bottle of spirits from his mother’s sewing basket, doused the piano and set it alight.

He got on the blind pony and rode out of Egypt.

The Wreck Cove relatives offered him a job sanding dories. James was meant for better things. He would ride to Sydney, where he knew there’d be more pianos.

Sydney was the only city on Cape Breton Island and it was many miles south, by a road that often disappeared, along an Atlantic coast that made the most of itself with inlets and bays that added days to his journey. There were few people, but those he met were ready with a meal for a clean clear boy who sat so straight and asked for nothing. “Where you from, dear, who’s your father?” Mostly Gaelic speakers like his own mother, yet always he declined a bed or even a place in the straw, intending that the next roof to cover his slumber be his own. Moss is the consolation of rocks, and fir trees don’t begrudge a shallow soil but return a tenfold embrace of boughs to shelter the skinny earth that bore them. So he slept outside and was not lonely, having so much to think about.

Following the ocean a good part of the way, James discovered that there is nothing so congenial to lucid thought as a clear view of the sea. It aired his mind, tuned his nerves and scoured his soul. He determined always to live in sight of it.

He’d never been to a city before. The cold rock smell of the sea gave way to bitter cooked coal, and the gray mist became streaked with orange around him. He looked way up and saw fire-bright clouds billowing out the stacks of the Dominion Iron and Steel Company. They cast an amber spice upon the sky that hung, then silted down in saffron arcs to swell, distend and disappear in a falling raiment of finest ash onto the side of town called Whitney Pier.

Here homes of many-colored clapboard bloomed between the blacksmiths’ shops and the boiler house of the great mill, and here James got a fright, never having seen an African except in books. Fresh sheets fluttered from a line, James guided the pony onto asphalt, across a bridge where he looked back at the burnt-brick palace a mile long on the waterfront, and contemplated the cleanliness of steel born of soot.

Plaits of tracks, a whiff of tar, to his right a dreadful pond, then onto Pleasant Street where barefoot kids kicked a rusty can. He followed the screech of gulls to the Esplanade where the wharfs of Sydney Harbour fanned out with towering ships from everywhere, iron hulls bearded with seaweed, scorched by salt, some with unknowable names painted in a dancing heathen script. A man offered him a job loading and unloading—“No thank you, sir.” New rails in a paved street mirrored cables that swung along overhead and led him to the center of town, an electrical train carriage sparked and clanged right behind him, the sun came out. Charlotte Street. Fancy wood façades rose three stories either side, ornate lettering proclaimed cures for everything, glass panes gloated there was nothing you could not buy ready-made, McVey, McCurdy, Ross, Rhodes and Curry; Moore, McKenzie, MacLeod, Mahmoud; MacEchan, Vitelli, Boutillier, O’Leary, MacGilvary, Ferguson, Jacobson, Smith; MacDonald, Mcdonald, Macdonell. More people than he’d ever seen, dressed better than Sunday, all going somewhere, he saw ice cream. And at last, up the hill where the posh people lived.

The pony sagged beneath him and cropped the edge of someone’s fine lawn as James came to the conclusion of his traveling thoughts. He would have enough money to buy a great house; for ready-made things, and a wife with soft hands; for a family that would fill his house with beautiful music and the silence of good books.

James was right. There were a lot of pianos in Sydney.

His Left Eye

The first time James saw Materia was New Year’s Eve 1898, at her father’s house on the hill. James was eighteen.

He’d been summoned to tune the Mahmouds’ grand piano for the evening’s celebration. It was not his first time in the Mahmoud house. He’d been tending their Steinway for the past year, but had no idea who played it so often and so energetically that it needed frequent attention.

The piano was the centerpiece in a big front room full of plump sofas, gold-embroidered chairs, florid carpets and dainty-legged end tables with marble tops. A perpetually festive chamber—even slightly heathen, to James’s eyes—with its gilt mirrors, tasseled drapes and voluptuous ottomans. Dishes of candy and nuts, and china figurines of English aristocracy, covered every surface, and on the walls were real oil paintings—one, in pride of place over the mantelpiece, of a single cedar tree on a mountain.

James would be let in the kitchen door by a dark round little woman who he initially assumed was the maid, but who was in fact Mrs. Mahmoud. She always fed him before he left. She spoke little English but smiled a lot and said, “Eat.” At first he was afraid she’d feed him something exotic and horrible—raw sheep, an eyeball perhaps, but no—savory roast meat folded in flat bread, a salad of soft grain, parsley and tomatoes with something else he’d never before tasted: lemon. Strange and delicious pastes, pickled things, things wrapped in things, cinnamon. . . .

One day he arrived to find Mrs. Mahmoud chatting in Gaelic with a door-to-door tradesman. James was amazed but glad to find someone with whom to speak his first language, since he knew few people in Sydney and, in any case, Gaelic speakers were mostly out the country. They sat at the kitchen table and Mrs. Mahmoud told him of her early days in this land, when she and her husband had walked the island selling dry goods from a donkey and two suitcases. This was how she had learned Gaelic and not English. Mr. and Mrs. Mahmoud had made many friends, for most country people love a visit, the mercantile side really being an excuse to put on the kettle. Often the Mahmouds carried messages across counties from one family to another, but good news only, Mrs. Mahmoud insisted. Just as she did when she read a person’s cup—“I see only good.” So when she peered into the tea leaves at the bottom of James’s cup he was neither frightened nor skeptical, but felt himself drawn in with an involuntary faith—which is what faith is—when she said, “I see a big house. A family. There is a lot of love here. I hear music. . . . A beautiful girl. I hear laughter. . . . Water.”

When the Mahmouds had saved enough, they had opened their Sydney shop, which thrived. Mr. Mahmoud had bought his wife this splendid house and told her to stop working and enjoy her family. And yet James never saw a sign of the family. Her children were all at school, and the big boys were at the shop with her husband. Mrs. Mahmoud missed her Gaelic friends in the country and looked forward to grandchildren. She never spoke of her homeland.

* * *

On this New Year’s Eve day, Mrs. Mahmoud greeted James with Bliadhna Mhath Ūr but didn’t show him into the front room, remaining in the kitchen to work alongside the hired Irish girl, who had a lot to learn. He proceeded there by himself, quite comfortable now in this house, took off his jacket and got to work.

He had already removed a few ivory keys and was bent under the lid behind the piano’s gap-toothed smile, so he didn’t see Materia when she stepped into the archway.

But she had seen him. She had spied him from her upstairs bedroom window when he came knocking at the kitchen door below, toting his earnest bag of tools—a blond boy so carefully combed. She had peeked at him through the mahogany railings carved with grapes as he entered the front hall and hung his coat in the closet beneath the stairs—his eyes so blue, his skin so fair. Taut and trim, collar, tie and cufflinks. Like a china figurine. Imagine touching his hair. Imagine if he blushed. She watched him cross the hall and disappear through the high arch of the big front room. She followed him.

She paused in the archway, her weight on one foot, and considered him a moment. Thought of plucking his suspenders. Grinned to herself, crept over to the piano and hit C sharp. He sprang back with a cry—immediately Materia feared she’d gone too far, he must be really hurt, he’s going to be really mad, she bit her lip—he clapped a hand over one eye, and beheld the culprit with the other.

The darkest eyes he’d ever seen, wet with light. Coal-black curls escaping from two long braids. Summer skin the color of sand stroked by the tide. Slim in her green and navy Holy Angels pinafore. His right eye wept while his left eye rejoiced. His lips parted silently. He wanted to say, “I know you,” but none of the facts of his life backed this up so he merely stared, smitten and unsurprised.

She smiled and said, “I’m going to marry a dentist.”

She had an accent that she never did outgrow. A softening of consonants, a slightly liquid “r,” a tendency to clip not with the lips but with the throat itself. What she did for the English language was pure music.

“I’m not a dentist,” he said, then rushed pink to his ears.

She smiled. And looked at the loose piano teeth scattered at his feet.

She was twelve going on thirteen.

Had she hit E flat things might never have progressed so far, but she hit C sharp and neither of them had any reason to suspect misfortune. They arranged to meet. He wanted to ask permission of her mother but she said, “Don’t worry.” So he waited for her, shivering on the steps of the Lyceum until he saw her come out the big front doors of Holy Angels Convent School across the street. The other girls spilled down the steps in giggling groups or private pairs, but she was alone. When she caught sight of him she started running. She ran right into his arms and he swung her around like a little kid, laughing, and then they hugged. He thought his heart would kill him, he’d had no clue what it was capable of. His lips brushed her cheek, her hair smelled sweet and strange, an evil enchantment slid from him. The salt mist coming off Sydney Harbour crystallized in the fuzz above his lip and alighted on his lashes; he was Aladdin in an orchard dripping diamonds.

She said, “I got five cents, how ’bout you, mister?”

“I have seventy-eight dollars and four cents in the bank, and a dollar in my pocket, but I’m going to be rich someday.”

“Then give me the dollar, Rockefeller.”

He did and she led him to Wheeler’s Photographic on Charlotte Street, where they had their picture taken in front of a painted Roman arch with potted wax ferns. He felt, before he learned anything about where she came from, that the photograph had made them one.

They continued on to Crown Bakery, where they shared a dish of Neapolitan ice cream and melted their initials onto the window. He said, “I love you, Materia.”

She laughed and said, “Say it again.”

“I love you.”

“No, my name.”

“Materia.”

She laughed again and he said, “Am I saying it right?”

She said, “Yes, but it’s cute, it’s nice how you say it.”

“Materia.”

And she laughed and said, “James.”

“Say it again.”

“James.”

It was when she said his name in her soft buzzy way that his desire first became positively carnal—he blushed, convinced everyone could tell. She touched his hair, and he said, “Do you want to go home now?”

“No. I want to go with you.”

They walked to the end of the Old Pier off the Esplanade, and looked at the ships from all over. He pointed. “There’s the Red Cross Line. Someday I’m going to get on her, b’y, a...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Permissions

- Dedicated

- Silent Pictures

- Book 1

- Book 2

- Book 3

- Book 4

- Book 5

- Book 6

- Book 7

- Book 8

- Book 9

- Reading Club Guide

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Fall On Your Knees by Ann-Marie MacDonald in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Literature & Women in Fiction. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.