- 368 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

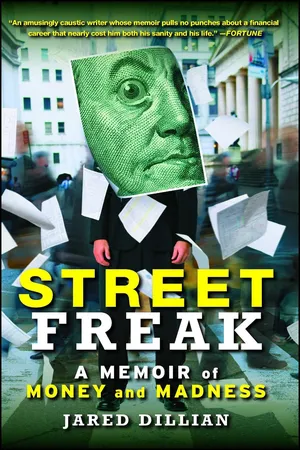

Like Michael Lewis’s classic Liar’s Poker, Jared Dillian’s Street Freak takes us behind the scenes of the legendary Lehman Brothers, exposing its outrageous and often hilarious corporate culture and offering a “candid look at the demise of a corporate behemoth” (Publishers Weekly).

In the ultracompetitive Ivy League world of Wall Street, Jared Dillian was an outsider as an ex-military, working-class guy in a Men’s Wearhouse suit. But he was scrappy and determined; in interviews he told potential managers that “Nobody can work harder than me. Nobody is willing to put in the hours I will put in. I am insane.” As it turned out, at Lehman Brothers insanity was not an undesirable quality.

Dillian rose from green associate, checking IDs at the entrance to the trading floor in the paranoid days following 9/11, to become an integral part of Lehman’s culture in its final years as the firm’s head Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) trader. More than $1 trillion in wealth passed through his hands, yet the extreme highs and lows of the trading floor masked and exacerbated the symptoms of Dillian’s undiagnosed bipolar and obsessive-compulsive disorders, leading to a downward spiral that nearly ended his life.

In his electrifying and fresh voice, Dillian takes readers on a wild ride through madness and back.

In the ultracompetitive Ivy League world of Wall Street, Jared Dillian was an outsider as an ex-military, working-class guy in a Men’s Wearhouse suit. But he was scrappy and determined; in interviews he told potential managers that “Nobody can work harder than me. Nobody is willing to put in the hours I will put in. I am insane.” As it turned out, at Lehman Brothers insanity was not an undesirable quality.

Dillian rose from green associate, checking IDs at the entrance to the trading floor in the paranoid days following 9/11, to become an integral part of Lehman’s culture in its final years as the firm’s head Exchange-Traded Fund (ETF) trader. More than $1 trillion in wealth passed through his hands, yet the extreme highs and lows of the trading floor masked and exacerbated the symptoms of Dillian’s undiagnosed bipolar and obsessive-compulsive disorders, leading to a downward spiral that nearly ended his life.

In his electrifying and fresh voice, Dillian takes readers on a wild ride through madness and back.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Street Freak by Jared Dillian in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Business Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Spartacus | October 2, 2007

The market has its own intelligence. It has a sort of malignant omniscience that dictates that the market will do whatever fucks over the most people at any given moment in time. It knows your positions, and it knows your fears. You are a sinner in the hands of an angry God, and your positions are going to pay. Like Santa Claus, sort of, except that the market doesn’t care who’s been naughty or nice; more often than not, naughty wins. The market cares who is the most exposed, who is the most out over his skis, and who has taken the most risk at any given moment. And once the market has ascertained the point of maximum pain, it will move, violently, in that direction, causing the greatest number of people to lose the most money.

It was moving that way for me today, having just been lifted on two million shares of IWM, an exchange-traded fund that tracks the fortunes of small capitalization stocks. The perpetrator this time was Spartacus, a monstrous hedge fund that managed billions of dollars in assets, run by only a dozen men and boys. Their trading desk consisted of a few Staten Island kids who had walked bass-ackward into a pot of gold, and was led by a Snidely Whiplash character, an evil genius Russian named Yevgeny. Yevgeny was rumored to have earned $50 million last year by picking off slowpoke retard ETF traders like me, hoovering money out of my P&L and into his in a brutal daily transfer of wealth.

Yevgeny didn’t give a damn that he was trading small cap stocks. He didn’t have an opinion as to whether small cap stocks would outperform large cap stocks on an economic basis. He was not making a strategic investment for the fund. For all he knew, he was trading May wheat. He cared about small cap only because it moved more than large cap; it was more volatile. And with greater volatility comes more opportunities to fuck people over. His trade was causing about $170 million to be rammed into two thousand tiny stocks, increasing the price of each of them by about .2 percent, getting two thousand CEOs momentarily excited for their companies’ prospects as they watched their tickers turn green on Yahoo! Finance—that is, until Yevgeny decided to turn around and sell.

This particular trade was already turning into a shit show, because when the fastidious, obsessive sales trader Andrew Duke quoted me, I thought I heard him ask for a price on one million shares. When the ticket arrived electronically on my screen, it read twice as much:

B IWM 2,000,000 SPRTC M048392049832

I knew I was in big trouble. I had lost $140,000 before I’d even printed the trade, given that the ETF had rallied several cents, and being short two million shares, I was losing $20,000 a tick. This was going to be an exercise in stuffing ten pounds of shit into a five-pound bag.

D.C. and I looked at each other. We had been working together long enough to be able to communicate by visual semaphore.

When I first met D.C., I didn’t like him. He was one of those perfect Ivy League mannequins, all J. Crew and hair helmet. He was also a Garden City guy. Garden City amounts to a massive Wall Street cult on Long Island, where any able-bodied male born within the city limits has a birthright to a job at a major investment bank. My disdain, at the beginning, was barely concealed. But D.C. was no ordinary cake eater. He was, literally, perhaps the best lacrosse player in the country. At five nine (generously) and 150 pounds, you wouldn’t figure him to be the world’s greatest athlete. He barely lifted weights and managed only the occasional run around Central Park. But he was, quite simply, the most coordinated human being on earth, and nearly ambidextrous at that. People who are gifted in one way are often gifted in others, and as a trader, D.C. was the silent assassin.

Once I began working with him in 2004, I liked him instantly. In addition to his physical gifts, he was the most competitive person I knew. I would occasionally tire of the Hundred Years’ War with the sales force. D.C. never backed down. He fought to make money on every single trade. And he was profoundly disappointed when he didn’t.

Perhaps the most interesting thing about D.C. was that he was exceedingly uninteresting. He had no deep, dark secrets, no skeletons in his closet, no illicit romances, no addictions, no nothing. It was impossible to believe that someone, especially in this business, could be that well adjusted. He was also a notoriously private person, so even if he was doing lines off a hooker’s fake tits at two in the morning in the W Hotel, I was never going to find out. In a way, his profound dullness made him just as much of a misfit as everyone else.

We were a great team: I had the raw smarts and the passion for finance, and he had the trading dexterity and the persistence. Occasionally, however, someone would sneak one past the goalie, and we would have to clean up the mess. This time, it was Spartacus, and this time, it was a million-dollar mess.

“Holy shit,” says D.C. I shrug. We’ll figure something out.

The market has its own chemistry, its own pressure. Traders, after enough time, learn to trade a market by feel. A trading floor is a room full of dogs, cats, and squirrels that can sense an oncoming storm. All morning, stocks had been like a manhole cover rattling around on the pavement, hinting at some imminent terrific explosion. When Yevgeny bought, the manhole cover shot up into the air.

I bought a million shares as fast and as sloppy as I could. Satisfied with my handiwork, I sat and trembled slightly as I watched IWM trade 20 cents above where I’d offered it. I lost $70,000 on the first million that I covered, and I was out $200,000 on the second million, which I hadn’t even touched yet. This is important, because I’d have to buy even more IWM in order to trade out of the dangerous position, and that would only make the losses worse. If you have one hundred thousand shares to buy, you’ll have to buy it at progressively higher prices to fill your order. The purchases you make at 10:30 drive up the cost of purchases you make at 10:35.

I was trying to restrain myself. The old me would have been pounding on the desk until I bruised the heels of my hand, and yelling, “Goddamn motherfuckers!” at the top of my lungs. But no matter what Spartacus or any of my other customers did, I was determined to act professionally and to not lose my cool. I had embarrassed myself one too many times with a hurricane of a temper tantrum on the trading floor, which was always followed up by an emotional hangover on the way home. The market, along with its malignant intelligence and chemistry, now had the new me: the cooler-than-the-other-side-of-the-pillow me, the future senior vice president and general sizeola Lehman Brothers trader.

I had two choices. I could hedge the trade now and lock in a sure $270,000 loss, which would destroy any profits we’d make for the rest of the day. Or I could wait to see what the market did and hope to buy back my IWM at a lower price later. The problem was, if I used a binomial tree to model each and every possible outcome, the likelihood of breaking even was less than one in twenty.

The probability was actually worse than that, given that it was Spartacus. The hedge fund was big enough and determined enough to push the market in their direction. When Spartacus bought, they didn’t buy just from one bank, they went around Wall Street and bought from everybody. I saw the prints going up.

09:52:02 IWM 1.0M 85.44 T

Only forty-two seconds later, another IWM transaction with another bank, and then another, each one driving the price higher …

09:52:44 IWM 2.0M 85.47 T

09:53:30 IWM 1.0M 85.55 T

09:54:11 IWM 2.0M 85.61 T

09:53:30 IWM 1.0M 85.55 T

09:54:11 IWM 2.0M 85.61 T

This is what we called “getting steamrolled” or “shitting on our print.” It meant that Spartacus had an order that was too large to give to a single counterparty, so they were splitting it up and spreading it around. It is good etiquette to give the entire order to one broker and let him work it over time to get the best price. It is bad etiquette to spray the street with your order flow like that—bad enough behavior to get you cut off from most places—but Spartacus denied it every time. They lied about their trades, even when there was a gargantuan pile of evidence against them. They were bad guys.

I turned to D.C., whom I always consulted in times of stress. “What do you think?” I asked him. He shook his head solemnly. This was out of his realm of experience, taking a $250K hickey before a trade was even half over.

“Okay,” I said to the speechless D.C., “I think Spartacus is trying to bully this market higher, and I think it’s going to run out of gas. No way am I buying back these IWMs—not until they get back to scratch.”

When I am in a losing trade, my body undergoes a physiological reaction. I cannot leave my seat; I feel chained to it. I hunch over my desk, staring at the screen, watching the chart go higher, tick for tick. I don’t really sweat, but I do tremble with fear and rage. I curse my life, and I hate myself in spite of the hundreds of thousands of dollars that I make. I am sick of being the doormat for all these arrogant hedge fund punks. I want to choke the living shit out of the sales trader that brought in the trade. I desperately need a drink. I feel the urge to verbally destroy the first person that talks to me. I start to think that torture is too good for some people. I hate everything and everybody, I see nothing but darkness, and the only thing that makes me feel better is even more hate; a higher, more cynical form of revulsion.

I watched the P&L on my GPM, the software which gave me a realtime view of my P&L: ($330,000). ($375,000). ($420,000). This is getting ridiculous. Am I just being stubborn? Or do I have a rational explanation for why I think the market is suddenly going to reverse in my direction? I can’t lock in a $420,000 loss. It can’t possibly get worse.

It gets worse. The market rallies more: ($610,000). ($700,000).

I had lost $700,000, and I hadn’t touched a share of the stock.

D.C. looked at me. “This is a disaster,” he said. “Yes,” I agreed, but I was frozen in my hunched-over position, staring at the chart, and I couldn’t manage to say much else. I felt like I’d swallowed a medicine ball.

It’s one thing to get run over on a trade. It’s another thing altogether to get run over for a whole percent in fifteen minutes. It’s unlikely for even entire asset classes—stocks or bonds as a collective entity—to move a percent in fifteen minutes. Such is Spartacus. You can’t just take the other side of their trades; you have to buy with. Once their trades start hitting the tape, every little weasel watching sees the prints and the price action and starts pushing it higher.

Then something miraculous happened. The market stopped going up. It began to consolidate. It seemed like it wanted to go higher, but it couldn’t. It was possible that Spartacus had bullied the market one too many times.

IWM started to trade lower. And lower. Now, the first instinct a trader has when he’s lost $700,000 is to close out the trade at down $600,000 and declare victory. I repeated to D.C., “I am not buying back a share of this thing until it gets back to unch.”

Now, unch, short for “unchanged,” is kind of an arbitrary level to aim for. Behaviorists, like the Nobel Prize winner Daniel Kahneman, believe that markets are driven by decision theory and information biases, and they call this “anchoring.” Nobody likes to lose money on a trade, so they’ll risk losing even more—an infinite amount—just to break even. It makes no sense to choose the price at which you got lifted as an anchoring point; in fact, it’s completely arbitrary. But this is what I was doing, and I knew it. I was ashamed of myself, but I was tired of losing money to these bastards, and I was going to break even on a trade if it killed me.

The P&L started to move my way: ($550,000). ($490,000). ($425,000). I began to ease the death grip on my mouse. I sat back in my chair a little bit. My neck muscles began to relax.

In some areas of the financial markets, it’s possible for both the buyer and the seller to make money on a trade. That may seem counterintuitive, but it happens quite a bit. In ETFs, however, it’s a zero-sum game. Stock goes up, buyer wins, seller loses. Stock goes down, seller wins, buyer loses. It turned my customers, even the friendly ones, into my enemies.

Every day I went to work and went to war with Spartacus. It was a war we could not win; most of the time we got run over on their trades, and if we ever made money on a trade, Spartacus would demand a price improvement, threatening to pull their business if we didn’t acquiesce. Heads I win, tails you lose. All I could do was try to minimize the damage. The fund had paid us $6 million in commissions this year, and we had lost all of it and then some; we found ourselves trying to use other customers to subsidize Spartacus’s losing business. I wanted them to just go away.

Andrew Duke didn’t want them to go away. He was the sales trader who had the unpleasant task of covering Spartacus within his larger book of bastards. He was a human shield. Tall and competent, Duke had worked his way up from being an “admin,” a glorified secretary, into a sales role. He was grumpy, and deeply cynical, like me. I liked him. But we were not friends. Wall Street had made us enemies.

Duke was compensated based on how much his customers traded with the firm. Whether they traded stock, ETFs, or options, his customers paid commissions. The more his customers traded, the more Duke got paid. Duke didn’t want Spartacus to go away. He wanted them to keep trading, even if it meant that, on balance, Lehman Brothers lost money to them. I was compensated by the profit and loss of my cozy little ETF desk, and I had no interest in losing money. It didn’t matter how much I complained to Duke that Spartacus was a loser—he was going to keep picking up the phone anyway.

Duke looked over at me. We made eye contact. He looked away. Duke knew that we’d gotten hosed on the trade, and he didn’t particularly want to have a conversation about it.

Meanwhile, IWM continued to fall. I started to jiggle my legs, which is what I did when I was happy. We were close to breaking even on the trade.

Enough is enough. I had a million shares to buy, and I started to bid, 100,000 shares at a time, in penny increments. Figure bid for a hundred. Ninety-nine bid for a hundred. Ninety-eight bid for a hundred. The market continued to fall. Come to Butt-head. I beckoned.

I finished buying stock. I looked up at GPM: ($70,000). We received $60,000 in commissions on the trade, so I had lost $10,000, which was essentially breaking even.

I high-fived D.C., which was sad, because we were high-fiving each other about losing money. I then walked over to Duke and stood behind him.

“How bad was it?” he asked.

“Take a guess.”

Duke winced. “I can’t even imagine,” he said. “Sorry about the mix-up, but I thought I pretty clearly said two million—”

“We lost ten grand,” I stated flatly.

Duke stood up and held out a hand. “Now, that is some trading. No way I would have been able to stay short that long.”

“Guess that’s why they pay me the big bucks.” In all honesty, Duke probably got paid more than me just to pick up the phone.

But I had gutted out a near seven-figure loss and made it all the way back to scratch, staring down one of the biggest hedge funds on the street. If trading had a hall of fame, I would be in it for that trade alone.

I got up from my desk. I had to hang a whizz—I’d swallowed down a giant coffee and been glued to the screens, white-knuckling the IWM trade for the better part of the morning. I walked down the aisle of salespeople and looked over their shoulders at their screens. A few had ESPN.com up. Takeareport.com. One girl was shopping for shoes.

Lazy. As I opened the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Prologue: Portrait of a Trader October 2, 2007

- Chapter 1: Spartacus October 2, 2007

- Chapter 2: Drive September 11, 2001

- Chapter 3: Vice Asshole Fall 2001

- Chapter 4: Found Money Winter 2002

- Chapter 5: Jay Knight Winter 2002–Spring 2002

- Chapter 6: Primate of the Year Summer 2002–Fall 2002

- Chapter 7: Dark Fall 2002–Winter 2003

- Chapter 8: T+1 Winter 2003–Summer 2004

- Chapter 9: Aggressive Summer 2004–Fall 2004

- Chapter 10: Thankyoudrivethru Fall 2004–Winter 2005

- Chapter 11: Piker Spring 2005–Fall 2005

- Chapter 12: Everything Is Not Going to Be OK Winter 2006

- Chapter 13: I Remember Winter 2006

- Chapter 14: Top Tick Spring 2006–Winter 2007

- Chapter 15: Grace Spring 2007–Winter 2008

- Chapter 16: Bad Trader Winter 2007–Summer 2008

- Chapter 17: Those Bastards Summer 2008–Fall 2008

- Epilogue

- Acknowledgments

- Copyright