![]()

![]()

CHAPTER 1

AREA AS CURRENCY

How Much Biocapacity Does a Person Need?

Everyone, big or small, has an Ecological Footprint. How much nature people need depends on what they eat, how they dress, what their home is like, how they move around, and how they get rid of their waste. All of that can be measured. The resulting data allows us to determine the area of biologically productive land and water that is required to grow food, produce fiber for clothing, build houses to shelter people, and absorb their waste. We can measure the carbon dioxide from burning coal, gas, and oil. In the end, we all live on what the “global farm” provides, and we can accurately measure what the farm provides, and what people consume.

Everyone understands money. People with money have more options, and possibly fewer worries, at least material ones. Those with enough money can live how and where they like. Everyone welcomes them. As long as they can pay, no one will show them the door. We can do many things with money. For example, we can compare things. Money also tells us how much everything costs. Once we know the prices, we can relate them to our income. How long do I have to work so I can afford this mobile phone? How much do I earn, compared to my expenses? Compared to last year? Or compared to the income of someone in Singapore?

Ecological Footprint accounting is a tool that, like money, asks the core question: How much nature does everything cost? How much biocapacity is required for a glass of orange juice, and how much for a liter of gas? And we can go further: How much nature does a person need? A person’s Footprint is a “currency” which is spent to provide services, to offer space for our buildings, to produce goods and to dispose of them. For a person, their Footprint is the sum total of all they require, including their waste (because waste too draws on nature). What the Euro, Dollar, or Yuan is to money, the hectare — or more precisely the global hectare — is to the Ecological Footprint.1

How the Footprint Works: Just Think of a Farm

The productive area of a farm is the farm’s biocapacity. What it can produce is determined by the area, as well as the productivity of each acre. In the US, pastures are sometimes measured in “cow-calf acres” — how many cow-calf pairs can be maintained on one acre. It is both the area and its productivity that counts.

The Ecological Footprint estimates how much farm it takes to produce what we consume, including everything we eat, all the fiber and timber we use, all the space to house our roads and buildings, and to absorb all our CO2 waste from burning fossil fuel. There is competition for our farm’s productive areas as a farmer can’t graze cows where she places her house, and can’t plant tomatoes where she builds her pond.

A farm family may want to know how hungry they are for food, materials, heating fuel compared to what the farm can provide. We can create the same comparisons to the world, countries, regions, cities, and even individuals.

Humanity’s biggest farm is our planet. Thanks to Ecological Footprint accounting, we come to realize that the way we operate our “farm” now is out of balance, as our collective demand exceeds by at least 70% what our planet’s ecosystems replenish.

Nature can make up for the difference by depleting stocks. Examples are cutting timber faster than it regrows, emitting more CO

2 than the planet’s ecosystems absorb, pumping up more groundwater than is being recharged, or catching more fish than restocks. This business model only works so long — whether for farmers or humanity as a whole.

As you look at the world from a biological perspective, you start to recognize that every country is essentially a farm with forests, pastures, cropland, etc. How big is this farm compared to the resource demand of its residents?

Illustration: Phil Testemale

Just as different currencies can be set off against each other, so can the Footprint’s area units. This is the point: that there is a single unit — a tertium comparationis — that everything refers to. Obviously, not every global hectare is identical, only sufficiently similar. But the same is true for money since one dollar for a person with minimum wage means something quite different than one dollar for a billionaire.

Therefore, in the same way one financial figure cannot describe the health of an economic entity, mapping the entire ecological reality with just one number is obviously crude and insufficient. In fact, Ecological Footprint accounting is not suggesting it is mapping the entire ecological reality. Rather it puts emphasis on biological resources (as we will discuss in more detail). The reason is that biological resources are materially more limiting for the human enterprise than the non-renewable resources like oil or minerals. For instance, while the amount of fossil fuel still underground is limited, even more limiting is the biosphere’s ability to cope with the CO2 emitted when burning it. The burning and coping are competing uses of the planet’s biocapacity. Similarly, minerals are limited by the energy available to extract them from underground and concentrate them.

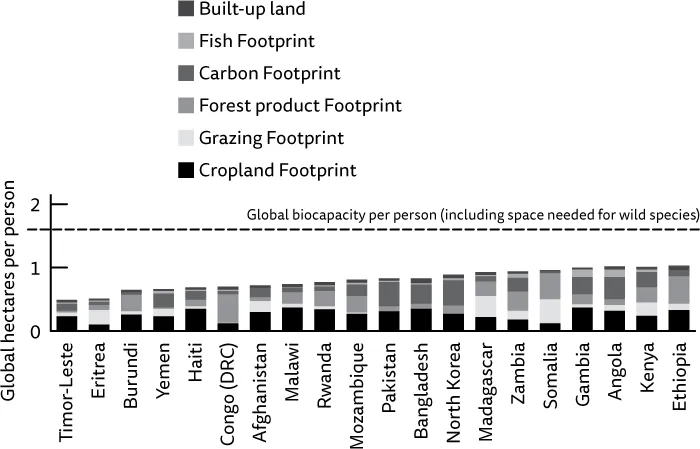

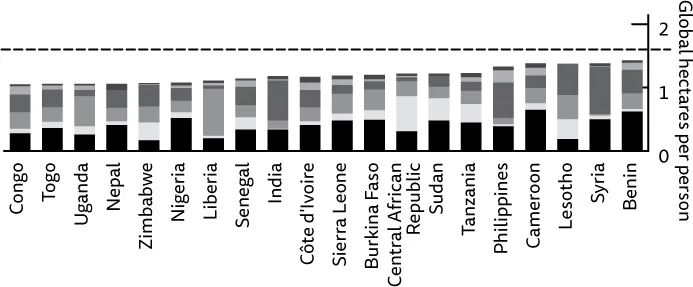

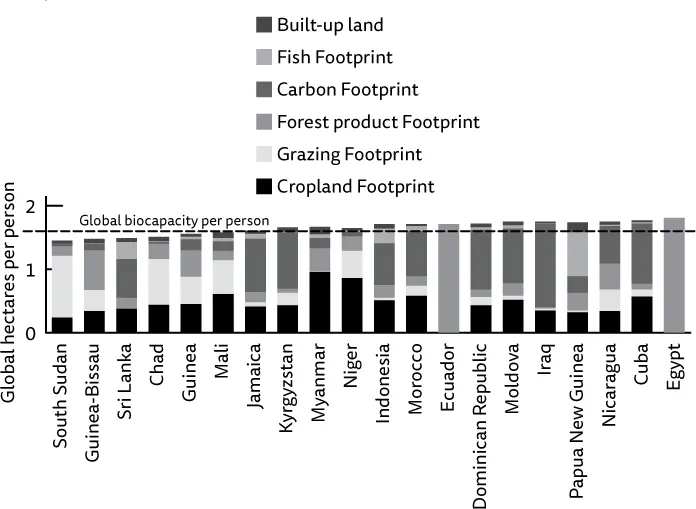

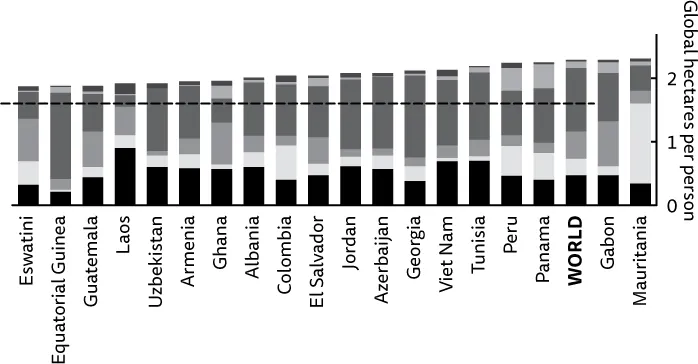

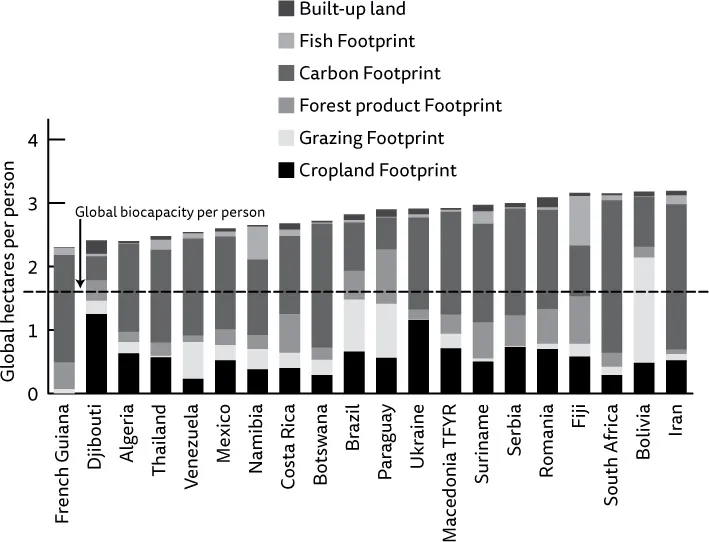

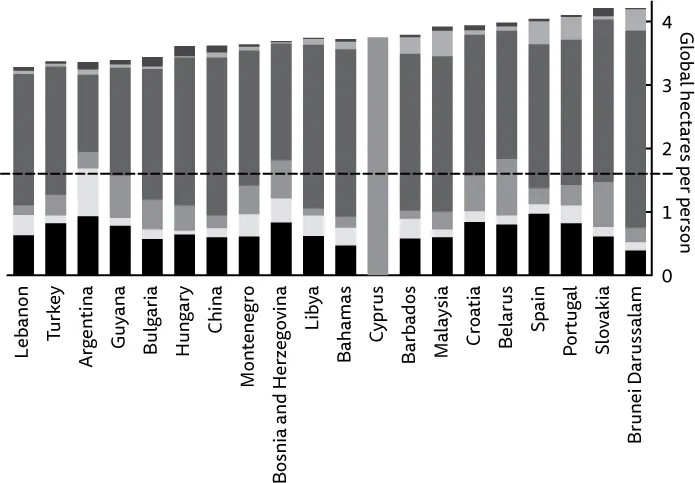

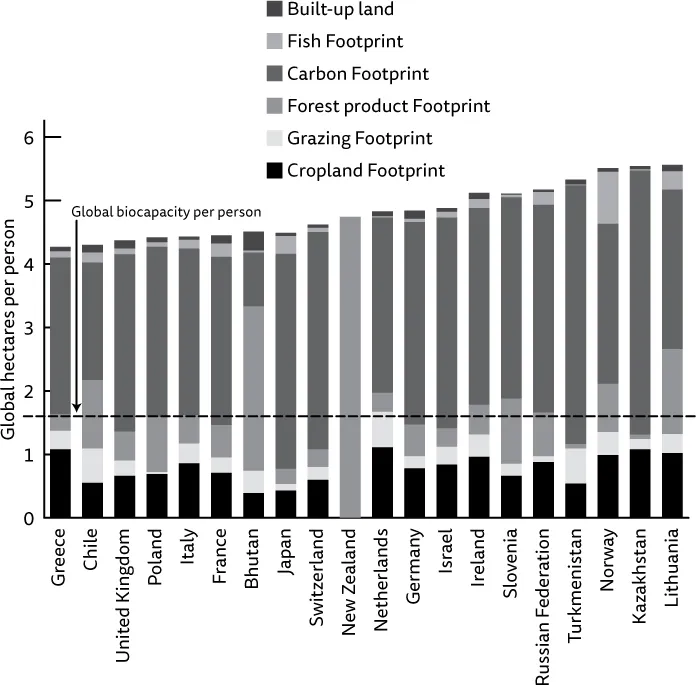

Figure 1.1. Ecological Footprint in global hectares per person, by country, 2016 data. In 2016, the world’s biocapacity averaged 1.63 global hectares per person. Credit: Global Footprint Network — National Footprint and Biocapacity Accounts 2019 edition, data.footprintnetwork.org.

Since biology and area are interconnected, Ecological Footprint accounts take areas of biologically productive land or water as their measurement unit. As we will see, such a simple unit makes communication more accessible, and our situations more understandable. Prices allow people to communicate with others about the high or low cost of a good. The Footprint enables us to have productive dialogues about the different ways we consume nature: about high or low consumption, about its impact on this or that ecosystem — summarized as one single number, the sum of all our demands on nature.

Let’s visit a department store. Just as the goods on offer carry price tags that identify their monetary value, and just as food products come with information about nutrients and ingredients, all products could come with an additional number that identifies the biocapacity that has gone into the product. The front of the price tag would tell us what we must pay, while the back would tell us how much nature was used. A block of cheese, a pair of jeans, a holiday trip — everything can be measured in biocapacity: what size of area is required to provide this product or service? For cheese, it is mainly the grazing land a cow needs to produce milk and of course the energy needed to turn milk into cheese. For jeans, it is the cotton field. Trips are enabled by many things, from aviation or car fuel to electricity for the trains, food, maintenance and cleaning of the hotel and washing of the linen. For many city dwellers, electricity may seem to come magically from the socket and milk from a carton, but behind everything we use there is a piece of nature.

Here, too, we have a parallel to money: as long as we have enough, all seems well and we take it as a given. But what if there isn’t enough? To have no biological capacity feels not that different from having no money. If, for example, you are stranded in a foreign city without cash or credit card, what will you eat? Where will you sleep?

What would happen if nature all of a sudden could no longer provide its wonderful services? If there wasn’t enough water to support life and economic activity in the first place? What if the oceans’ fishing grounds shrank or even collapsed while demand for fish continued to rise and fish became rarer and more expensive? What if the fields in one’s backyard couldn’t produce enough to sustain one’s family and people — like many in rural Bangladesh — didn’t have the money to buy additional food? What if the forests and oceans one day all of a sudden no longer absorbed carbon dioxide but instead released the gas they had stored into the atmosphere? What then?

Money is our core economic measure for assessing value. But money can do more than simply measure value: it is also a means of payment and, as such, gets passed from person to person. The Footprint can’t do that. We can exchange the fruits of biocapacity, for example by importing timber and exporting meat. People or trade statistics may not recognize that, since it is not actual Footprints units that get traded. Rather, we can measure the Footprints of timber and meat that is traded.

Money is also a kind of storage system for one’s assets (as in a savings account or a portfolio), but that, too, is different with the Footprint. Nature’s assets always exist in nature itself, and the Footprint, as an accounting method or a code number, only measures and identifies them. Whereas money is recognized if not idolized as valuable, nature’s capital is undervalued. We behave as if nature were infinite and inexhaustible in its provision of riches to humanity. In the long term, however, it is nature that is the most valuable asset, whereas money is just a symbol.

Of course, things exist that we cannot buy, such as true love. We cannot assign it a monetary value. Another example is the atmosphere. People have developed the habit of treating our atmosphere as a free garbage dump for their emissions. As with money, there are areas where the Footprint does not apply. A rock, for example, has no Footprint. It simply is, and its existence requires no measurable consumption. Animals, on the other hand, do have a Footprint; they breathe, drink, and feed, consume biocapacity and hence area. A fish eaten by a seal is no longer available to us, or only indirectly when in turn we eat the seal or use its pelt.

How much biocapacity do we need? In order to eat, to clothe ourselves, to build our houses and heat them, also to travel and to transport any goods, we need the supplies that nature provides. In the process, we leave behind solid, liquid, and gaseous waste. Nature has to cope with that too. As we move through the world, we leave behind our “Footprint.” Some of us tread with heavy steps, while others have such a small and light step they hardly touch the ground. But every human being, big or small, leaves a trace as long as they live. It is this trace that the Footprint metaphor refers to.

The Ecological Footprint measures not only the demands an individual puts on nature but can equally be applied to the population of cities, nations, or humanity as a whole.

Let’s take fossil energy as an example: Since the Industrial Revolution, we have availed ourselves of massive amounts of nature’s resources of coal, oil, and gas, when in fact these are non-renewable resources, or to be more precise, resources that renew themselves only over enormous periods of time. We extract them from the Earth’s crust and bring them to the surface and hence into the biosphere. For Footprint calculations, the amount of coal or oil underground does not enter into the equation. After all, these materials are not part of living nature but came to be over millions of years; in that sense, they are assets more like a piece of gold or a painting by Picasso. Also, they turn out to be rather plentiful compared to what the biosphere can handle. It is by using coal or oil that we consume nature, and this consumption is what Footprints measure.2 When such quantities of fossil energy are burned, carbon dioxide is released. And then our biosphere has to cope with that, because this is new carbon dioxide that previously was not part of the natural cycles.

To prevent an increasing concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere that will lead to a long-term destabilization of our climate, that additional carbon dioxide should be removed — but, so far, only a small portion has been removed. The remainder we leave for nature to cope with it. A good percentage of the excess carbon dioxide is now being absorbed by the oceans (and further acidifies them), some is absorbed by ecosystems on land, but some land uses also lead to net emissions. A lot of the carbon dioxide is left in the atmosphere and accumulates. The Footprint method therefore asks: how big an area, how much forest, is necessary to absorb the remaining amount of carbon dioxide? Research shows that an average hectare of forest on this planet, if managed for climate protection, can annually absorb roughly the same amount of carbon dioxide as is released by burning 900 liters (or 240 gallons) of gasoline.3

Over the past 200 years, the atmosphere’s carbon dioxide level has risen by about ⅓ from 278 ppm to more than 410 ppm, and more if we include other greenhouse gases. We are obviously not dedicating enough of the planet’s biological capacity — mainly forests and oceans — to sequester the combustion residues as quickly as we generate them.4 One reason is that there are many other competing demands for the planet’s biological capacity as well. Plus, there isn’t enough to do that: Recently, the carbon Footprint has become so large that it alone is now exceeding the Earth’s regenerative capacity.

Still, if we deploy area to sequester more carbon dioxide, we could have considerably less biocapacity left for other purposes, such as the production of food, fiber, or fuelwood, or the creation of urban areas. Grazing and crop agriculture can i...