![]()

1

Introduction

For those who want to overthrow the system that oppresses them, it helps to learn and remember and to be inspired by others who have tried to do the same.

A revolution took place in Portugal. We can date this precisely: between 25 April 1974 and 25 November 1975. The revolution was the most profound to have taken place in Europe since the Second World War. During those 19 months, hundreds of thousands of workers went on strike, hundreds of workplaces were occupied sometimes for months and perhaps almost 3 million people took part in demonstrations, occupations and commissions. A great many workplaces were taken over and run by the workers. Land in much of southern and central Portugal was taken over by the workers themselves. Women won, almost overnight, a host of concessions and made massive strides towards equal pay and equality. (Strikes towards equal pay were also made by men in favour of women – it was a class approach not just gender.) Thousands of houses were occupied. Tens of thousands of soldiers rebelled. Nobody predicted that so many would try quickly to learn and put into practice the ideas that explode from those who are exploited when they try to take control of their own destiny. Portugal 1974–1975 was not an illusion. We have to remember, celebrate and learn from Portugal. That is why this book has been written.

This is not the first book which tries to capture and celebrate our achievements. I am deeply indebted to some of the work and research that has been done already.

The history of the Portuguese Revolution, as with the history of any revolution, is the history of the State, which could no longer govern as before and the history of those who were no longer willing to be governed in the same way. This book deals with a part of the construction of an alternative, of those who were no longer ‘willing to be governed’ as they had been before.

People changed. They changed because they refused to fight in the war, because they demanded a say in where the crèche was located or in the accounts of the companies. They changed because they learned the meaning of direct democracy in many forms: possibly because of direct person-to-person and face-to-face democracy, or the vote of a raised hand in the residents’ commissions, committees of struggle, occupied lands, workers’ commissions, soldiers’ assemblies, and general meetings of workers or students.

New forms of democracy were forged, as they always are when people become engaged in struggles. Democracy becomes our weapon. It is far more than merely putting a cross on a ballot paper once in a while.

Never before in the history of Portugal did workers have such a consciousness of being workers and of being proud of it: ‘There is only serious freedom when there is peace, bread, housing,’ they sang.1

The revolution profoundly changed Portugal. But the revolution did not change the relations of production in a lasting way. The State recovered, the regime stabilised itself and governments operated without the involvement of the masses of people who had helped make the events in 1974–1975.

The revolution was defeated. It was not crushed like that in Chile the year before or the uprisings in Hungary in 1956. As always, the victors write and rewrite history. The scale and magnificence of the struggles below and the capacity to involve is overwritten and lost. Some have likened it to a hallucinogenic dream, others a forgotten dream and yet others an impossible dream. It is almost as if nothing really happened – as if we have nothing to learn.

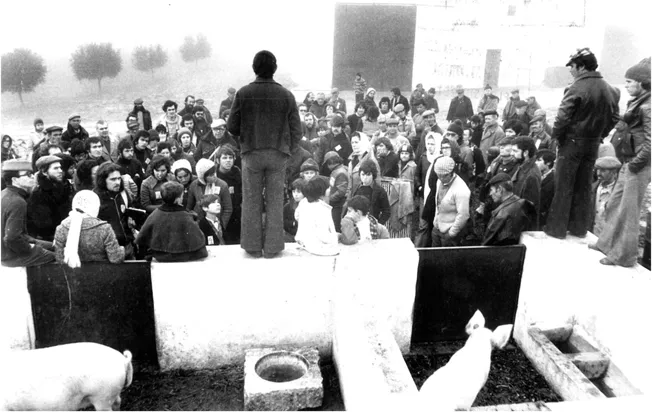

Photo 1 The community of an occupied farm holds a meeting to decide how the work of picking the olives should be shared out. (Socialist Worker)

Most of the accounts that appeared at the time – and since – have been top-down, often written by ‘personalities’ focusing perhaps on themselves, or upon the army and senior military personnel and bourgeois machinations and almost never on the povo, that is, the people. Where the working class is referred to, for example, ‘the threat of labour unrest’, it is as seen from the outside as a problem rather than the solution.

The rewrites have marginalised the working class, and I mean this in the broadest sense. The leaders of the Portuguese Revolution were those who lived from their work, their children and families: intellectual and manual workers, men and women, skilled and unskilled.2 This included ordinary soldiers, who came from the ranks of the working class, and who were immensely politicised by the struggles of their brothers and sisters.

The revolution has been marginalised in many other ways; but actually, Portugal had been marginalised before the revolution, as being a backward fascist corner, not as an outpost of capital. I prefer not to use the word fascism to describe the autocratic dictatorship but I respect the rights and sense of those who suffered under the dictatorship to call it fascist. The fact is that Portuguese capitalism was locked into international capitalism. The Portuguese empire became one of the pillars of the free world, a founder member of NATO (1949), and recipient of modern arms and expert advice on techniques of repression. Capital was investing in the shipyards and large modern factories in the industrial belt of Lisbon. The African wars could not have continued for very long without NATO weaponry and equipment. International capital was benefitting from the supply of raw materials for Angola and the sourcing of cheap labour for South Africa.

Hence, Portugal cannot be isolated from the international financial crisis – one symptom being the 1973 oil crisis and the collapse of the Gold Standard.3 Portugal was also an echo of political turbulence. One might recall May 1968 France with student riots and a nationwide general strike and the Italian ‘hot autumn’ of 1969, strike waves in Germany and Britain in the early 1970s, and the struggle against military rule in Greece in 1973–1974.

In charting the chronology of the revolution, the focus is first and foremost on strikes, demonstrations and occupations of factories, businesses and homes. This is distinct from the existing historical literature which emphasises the dates of the coups and changes of provisional governments and the role of the armed forces. My angle shifts from that of institutions to the social field. The coups of 28 September 1974 and 11 March 1975 came about because of the struggles in workplaces and communities, and the coups were defeated because of these very forces. I advance the hypothesis that 11 March 1975 was the result of the extension – detailed throughout this book – of workers’ control. The fall of the Fifth Provisional Government at the end of August 1975 was not the end of the revolution, but merely the maturing of the revolutionary crisis, that is, the moment when the political parties, namely, the Popular Democratic Party (PPD),4 the Socialist Party (PS)5 and the Portuguese Communist Party (PCP)6 at the top of society and the Armed Forces Movement (MFA), allied together or not were no longer ‘able to govern’ and those from below were ‘no longer willing to be governed’.

Despite the pretensions of the Socialist and Communist Parties, state and revolution drifted apart in 1974–1975. Indeed, the revolution was constructed against the State.

So this is a people’s history. In the last decade, people’s histories have widely surfaced as a genre after the unexpected success of Howard Zinn’s A People’s History of the United States.7 They are different from conventional historical accounts, representing more closely ‘History from Below’ to use Hobsbawm’s phrase. Howard Zinn said that histories of the people are the voice of those who had no voice. Chris Harman, author of A People’s History of the World,8 called them the ‘scaffolding of society’.

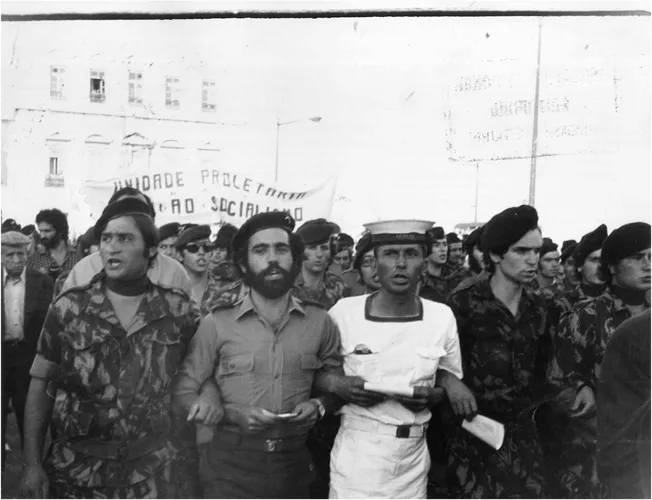

Photo 2 Workers and Soldiers Demonstration, 16 July 1975. Armed soldiers (and tanks) support a demonstration in Lisbon called by Inter-Commissions (federation of shanty town neighbourhood committees). (Socialist Worker)

In A People’s History of the Portuguese Revolution, readers will find a history of resistance, of the ‘voiceless’, those who have been habitually absent in history books, buried by decrees, diplomatic statements, back-room deals and conventional political struggles. You will not find here a history of colonial war, but the history of resistance to forced labour in the colonies or a history of anti-war resistance. You will not discover the history of the fall of the provisional governments, but the history of workers’ control which led to the fall of various coalitions that tried to rule the strange ungovernable people of Iberia – people who learned for the first time how to govern themselves. You will not read here the indispensable history of political parties, but that of the working class in its widest sense. Nor will the reader find a history of the intense diplomatic relations of the period, yet there will be references to solidarity movements between countries by those from ‘below’.

The authors who have dedicated their research to people’s histories have clearly distinguished themselves from those who see the people as a spontaneous and disorganised crowd. This book is inspired by a broad concept of the working class; it highlights the history of grass-roots workers’ organisations that were often closely linked to political leaders and parties from the far-left. While not exhaustively studied in this book, the political groups are fundamental in explaining the dynamics of the revolutionary process. But I would like to suggest that many activities were spontaneous – well not quite spontaneous.

A total history, desired by all, is not only the history of resistance. But it cannot be accomplished without the history of resistance: those who did not accept orders without first contesting, discussing and voting on them.

Raquel Varela,

November 2018

![]()

2

The Seeds of Change

People make their own histories, but not in circumstances of their own choosing.

Karl Marx: ‘The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Bonaparte’1

Whose Power?

While there were many momentous moments, probably the moment in which the Portuguese Revolution came closest to insurrection, that is, the moment in a revolution where the conquest of the State under the leadership of workers takes place,2 was to be found at São Bento on 13 November 1975. São Bento, in Lisbon, was the seat of the Portuguese parliament. It was here that the Constituent Assembly and the Government were being held hostage, surrounded by a mass of almost 100,000 people, the majority of whom were construction workers. The scenario was almost unreal: it was Europe, in sunny Lisbon, the disproportionately large capital of Portugal, and the capital of the last colonial empire in history. If it were not for the helicopters, the hostages in the São Bento Palace, including the prime minister, would not even have received food or blankets. Outside there was a gigantic demonstration of workers who elbowed each other and literally stood on top of each other on the palace steps with red flags and banners, yelling slogans.

Suddenly, a cement truck entered the square and crossed the mass of demonstrators who surrounded the Assembly and, with smiles and raised fists, they moved aside to let it pass. On top, there were two men. One of them wore jeans and an o...