eBook - ePub

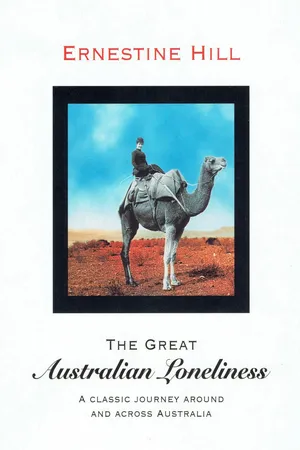

The Great Australian Loneliness

A Classic Journey Around and Across Australia

- 330 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

'This is the story of a journalist's journey round and across Australia... It was in July 1930 that I first set out, a wandering "copy-boy" with swag and typewriter, to find what lay beyond the railway lines...' Ernestine Hill's classic account of travelling in the Australian outback, in a pilgrimage of many years and 100,000 miles. "The most picturesque account of our outback that has yet been written... a vivid and arresting page of Australian history." - Adelaide Advertiser "With zest, humour and a warm sympathy, Hill brings life to a frontier..." - New York Herald Tribune "A travel book that is a pleasure to recommend." - The Irish Times

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Great Australian Loneliness by Ernestine Hill in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Australian & Oceanian History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Book II

ROYAL MANTLE OF THE TROPICS

CHAPTER XIV

THE APEX OF AUSTRALIA

IT is not until you cross the Territory borders that ‘the royal mantle of the tropics’ falls upon the West Coast. The far north of Australia comes as a splendid surprise. There are no infinities of crocodile mud-flats and deserts of desolation that wring the heart, such as one would believe from the vagueness of the map, but a country of wonderful permanent rivers, some of them 250 miles long, rising ninety feet each year in flood, breath-taking in their beauty—Nature run riot in fertility to a dense tangle of jungle extending 200 miles south from the sea. Rankly tropical, the very far north is a stranger to the rest of Australia. Had the coastline extended for another hundred miles, we would have had the jaguar and the monkey.

Blessed with prolific tropical soils and sub-soils, with a mineral belt of potential wealth that extends for 10,000 square miles, and the most extensive cattle-breeding country of the Continent, to-day all unexploited, the Territory is that saddest of all prospects, a country without a future. The great need is population. Census returns disclose that there are 3306 Europeans in 553,000 square miles, and 744 full-blooded non-Europeans, and 800 half-castes, and, roughly estimated, 25,000 blacks. So that the black outnumbers the white at nearly ten to one. When it is remembered that at least 10 per cent, of this European population consists of Government servants in residence for three years, that the half-caste population has doubled itself within the past decade, and that the increase in the white is about seventy persons per annum, the future of White Australia in the north looks very black indeed.

Wandering there, I stumbled upon all the traces of a century of failure. I heard everywhere the stories of white men taking on a job too big for them. Too many of the deaths are grim, untimely tragedies, of thirst, and fever, and suicide. The only country of its latitudes where a determined and sustained endeavour has been made to colonise exclusively with the labour of the white man, as yet, because there are so few of him, the jungle wins.

Outside Darwin, that ‘gateway to the East’ that never opened, and the tiny settlements of a railway that straggles away into the bush, are but a scattering of cattle stations, 50, 100 and 200 miles apart. Each a million acres of empty bush, they nearly all belong to the great English firm of Vesteys, with a manager and a few blacks on each to hold the country, and a white woman in residence here and there. Wives are not encouraged in the wilderness. The reason given to me was that the men hang round the homestead too much when there is a woman to keep it comfortable, instead of getting out with the cattle. The results of this virtual martyrdom of segregation are often obvious and regrettable. For the rest, a handful of buffalo-hunters and prospectors for gold, and old pioneers, ‘just sitting down,’ as they told me, by a billabong, hoping for the best, and letting the dreamy tropic days go by. They have done their bit, but the youngsters will not follow.

Mines of gold and tin and lead and silver and wolfram, that yielded hundreds of thousands of pounds’ worth in the ’eighties and ’nineties, are deserted. Cotton of a hundred plantations is now practically indigenous. Coco-nuts and bananas and blue maize and millet and rice and vanilla and indigo are threaded through the native bush, and the bush-men are lighting their pipes with what once won prizes as the finest cigar leaf, plucked wild at a gilgai. The buffaloes, Brahma cattle and sturdy little Timor ponies that the early settlers brought to the yoke of colonisation are galloping mad along the flats of the Mary and Alligator rivers, and at Port Essington, the shy little English deer, never molested by the black tribes, still peer between the leaves of the pandanus. For the Territory is too generous. Everything flourishes far too well, making it difficult for a few white men to cope with. Superstitious old hands, reviewing its history for seventy years, told me that the country was cursed, but it is cursed only with the mistakes of misunderstanding and the hoodoo of its loneliness.

The dominant need is for the great national stimulus of home life, a blessing it has never known. In a word, its crying necessity is more white women, who will share the lives of their own white men so patiently plodding on through the years, and rear children who understand and love the country for its own sake. Statistics show that there are less than 1500 white women in the Territory, one to every 360 square miles!—and most of those in Darwin. Wherever there is a white woman on a station—and sadly few there are—that station is a pleasant and prosperous one, and her influence is deep and illimitable. The blacks are clean, the homestead is clean and pretty, the stockmen are cheery—they have a home to come to, someone to listen to their troubles, and see that they change their shirts, and write to their mothers, and jest with them, and keep them human. In a climate that is perfect for most of the year, and, at its worst, little more trying than the summer heat of Sydney and Melbourne, these women, making home for their children in the health and freedom of the bush, are holding the North for us, which without them must slip back, ever and again, to a haunted, homeless loneliness. Far greater than the need of £15,000,000 railways and naval bases and garrisons and aerial expeditions and the discovery of gold is the Territory’s dire need of the white woman.

After a pretty hard day, the Surveyor-General and I pulled in to Katherine township at nightfall, to be met by a hearty Irishman surveying the world in company with a lean and lanky pet brolga from the front verandah of the pub.

‘Where’s your otto-mattick?’ he demanded of me. ‘Ivery sthranger that comes to the Katherhyne has a camera in wan hand and an otto-mattick in the other, kapin’ th’ wild men covered while they take our photygraphs.’ But the wild men were anything but hostile, the boisterous cool shower a joy, and the great glass jugs of goats’ milk on the dinner-tables a good refresher.

Katherine township is a few angles of tin roofs among the trees on the banks of the beautiful Katherine River, winding a hundred miles down through the jungle to join the Daly. The blacks are numerous and picturesque all along that river-bank, bodies of wonderful symmetry, skins of silky texture and black as boot polish. All they wear is a scarlet naga and a few bamboo armlets, except when they come in to the town to do odd jobs.

There were a few railway cottages, a one-roomed school with three white pupils and eleven Chinese, and a good few camps of old white wanderers ‘retired,’ spending their pensions on flour and tobacco, each with a nigger as gentleman’s man to catch him kangaroo and barramundi. One of them, Raparee Johnson, was living in an ingenious adobe home he had made of ant-bed reinforced with bottle-tops.

Tim O’Shea’s pub was the centre of attraction, with a festoon of home-made electrics picking it out from the Chinese shacks at night. It was said that Tim had taken £90,000 in the railway extension days of 1926, when thousands of men of all nations were camped in gangs on the line.

Some epic cheques dissolve, like Cleopatra’s pearl, in the beer glasses of these outback pubs. The men of the bush watch them fade away without a twinge of regret. Katherine boasted the record, £700 in a scrap of paper that one Len Adams, once passed over the bar. He was a young English teamster from the railhead out to Wave Hill, 800 miles there and back. Finishing up five exemplary years, he sold the horse-team, drew his cheques, and set out for the lights of London. At Katherine he stopped for a whisky, and forgot where he was going.

The cheque and the celebrations lasted six months, and then Len Adams went out to Victoria River to find a job. He rode in to the station on a January day, and walked over to the well for a drink of water. The pannikin fell from his hand—and Len Adams was a bar-room yarn.

A tragic country, with the need of women to care for its men. Of all those commemorated in that graveyard in the grasses, very few had ‘died in their beds.’ It isn’t done.

A day later, I left for Darwin on the Sentinel.

‘First Ladies.’ A bunch of lubra faces framed in the carriage window, all with a tooth or two knocked out, and all laughing, passengers on the Birdum-Darwin express, that stops every time a bushman leaning against a swag gives her a hail.

There is a train a week in the Territory, and it runs practically the whole gamut of Territory history and scenery, one of the world’s best for interest and diversion, though it carries more swags than suit-cases. All the blacks of the countryside put on their dungarees and Mother Hubbards, and straggle down to the sidings to watch it go through, and old settlers, camped on the creeks, rectify their calendars by its whistle. They call it Leaping Lena. One terminus is Birdum, three shacks in the bush, and the other the first breaker of the Indian Ocean. The northern section of the trans-continental railway begun in the ’eighties and never finished, it has taken the little 3 ft. 6 in. gauge fifty years to struggle down 300 miles, and there are still 700 miles of wilderness to cross before it links up with the southern section at Alice Springs. But there are greyheaded optimists who believe that one of these years they will see it completed, to bring population and prosperity to the North.

In the pungent wet season it was here that I began to smell the Territory, Chinese scents of lancewood and steaming lagoons and jungle grasses, blacks and pandanus, and later the reek of the mangrove creeks and the crocodile rivers. The Sentinel—Leaping Lena’s official name—is a string of scarcely glorified cattle trucks that never fails to provide a good jest at the expense of overland travellers. So uncomfortable are its narrow wooden seats that those who know them always prefer to sit on the floor. But there is a humour and a hearty democracy about it that no other train in Australia can boast. The guard has been known to bring round ‘beer for all aboard’ on the Sentinel.

Passengers are as varied a collection of human oddities as the world can offer—buffalo-hunters and anthropologists, mining agents and half-castes, A.I.M. sisters on errands of mercy bent, white men seeking medical attention for spear-wounds, native murderers, globe-trotters and stockmen, Russian peanut-farmers and Chinese women in their national dress, with frequently a tribe making down to Darwin for ‘bigfella corroboree’ in the compound there. A number of native prisoners from the Centre were aboard, to be tried on a charge of murder. Passing a good patch of melons, the Sentinel slowed up, and the natives were freed to go and collect them. Well under way, they struck a better patch of riper melons, threw the first lot overboard, and let the natives off the chain again.

Past the few Chinese shacks of Mataranka, and Marran-boy, nothing but a sign-post leading to abandoned tin diggings twelve miles away, we left the Katherine for lunch at the inn, kept by Mr. Tim O’Shea and his seven pretty daughters, a galaxy of Irish beauties unique in the Territory, and pulled in for the night at Pine Creek, where the grasshoppers are as big as birds and the frogs have voices like goats. Howley and Union Reefs and Zapopan, Rum Jungle and Grove Hill and Brock’s Creek are tiny settlements with two or three whites and half-castes and blacks, ghosts of the once-great gold mines. At Stapleton I met the Sargents, a Canadian family, who demonstrate just what the right type of settler can accomplish in this country. Mother and father and a large family of mostly girls came to Stapleton twelve years ago, and they now grow and manufacture everything for their own sustenance—cassava and rice-flour for their bread and buns, an excellent garden of vegetables, of tropic fruits, millet for their brooms, horsehair for home-made halters and upholstery, raw-hide for their bed-mattresses, strung across saplings. The only commodity they find it necessary to buy is tea. These girls ride round the cattle, erect their own fences—thirty miles and more of wire hand-twisted round bush-posts—and descend fifty feet in the earth to dig for lead. A remarkable little group, content in their isolation, they are all well educated by correspondence, and not one of them has ever been as far from home as Darwin.

On went the little train, almost in the towering grasses and swamps of the wet season, past the Adelaide and the Darwin rivers, and then twenty miles through a thick jungle of eucalyptus and milk-wood and fan-palm and sago-palm and screw-palm, to pull in beside a pearling-camp on the Indian Ocean, and wake Darwin from siesta with its shrill little whistle, in time for afternoon tea.

To come into Darwin in the wet season is to tiptoe across the bounds of possibility into an opium dream. The personality town of Australia, vivid, illogical, fascinating, the population, of about 2000, numbers some 43 races, each one distinct and sometimes all blended up in one, with complexions that range from gun-metal to old ivory. Government officials, immaculate in white; Larrakeahs and Wargaits, their skins gleaming like glossy black taffetas, riding bicycles about under the banyan trees; Chinese ladies with pantaloons and blue umbrellas; swarthy Filipinos, Fijians fuzzy-wigged, and grave Doric beauties, their fair hair parted above ‘the brow that launched a thousand ships’—these are some of the characters in Darwin’s musical comedy. All through the winter months, when the tourists come by on the Singapore ships and the overland chars-a-bancs, to find a little huddle of latticed houses in bareness by the sea, Darwin is demure and not nearly so intriguing. You must catch it in the gipsy moments of monsoon, when the electric storms sweep over and the tropic trees are in blossom, a background of barbaric glory for its thousand coloured faces.

Built out on the extremity of a small forked peninsula, north, south, east and west, dense jungle headlands drop a sheer eighty feet to the corroboree-figured rocks of the sea, a tangle of chartreuse sunlights making a harlequinade in green. Lining finger-nail curves of beach, tall coco-nuts toss back the sunlight like a juggler’s knives. Against bamboo lattices, yellowed with sun and rain, are painted the poincianas.

'Wickedly red and malignantly green,

Like the beads of a young Senegambian queen.’

Like the beads of a young Senegambian queen.’

the dragon limbs of frangipani, crowned with creamy perfumed flowers, lanterns of the cassia, leopard crotans and trailing purple bougainvillea, the soundless golden bells of alamander, tasselled hibiscus, and deep crimson cluster of quis qualis, the Japanese jasmine, that changes colour at dusk.

From beneath the deeper shadow of tamarind and banyan, those lattices shine mysteriously in the evenings, suggesting romantic intrigue, but really merely bridge; and along the jungle-tracks, lost in grasses frailly coloured as a lunar rainbow and fourteen feet in height, there comes the acrid, heavy-sweet scent of—might it be opium, or just the dusk-scent of the flowering henna?

In the harbour, beneath the splendour of high-piled cumulus, the tide of the tropics is hurrying in and out like a live thing. Whole beaches move before the eyes, with flocks of indeterminate grey sand-pipers and the crawling of a million million hermit-crabs. From every lily-pool rises a vibrant symphony of frogs, and in the bush foliage, alight with the flight of butterflies, finches and parakeets of brilliant plumage forever writhe and flutter, restless and watchful as the bright-eyed mottled lizards.

Such is the fantastic setting for the drama of Darwin, solitary jewel of a black man’s country, an alien in Australia. What can be its future? Already it needs an ethnologist-biologist to sort it all out, a Darwin himself, intent on the origin of human species, for its genealogical trees are grotesquely twisted and intertwined, even as the creepers of its jungles, or as the writhing mangrove roots of its foetid salt creeks.

To overlook the vestibule of its one picture show on Saturday night is to gaze upon a kaleidoscope of humans that surely no other town of its size in the world can boast. Eagerly taking their turns at the ticket-windows, and the barrow where a Chinese cook sells hot potato chips and sate on sticks, you will see stockmen in sombreros, men of the donkey teams and the pearling-luggers, Chinese women in embossed silks, Melville Islanders who have paddled sixty miles across turbulent crocodile seas in a ten-feet bark canoe to see Greta Garbo look pensive in a divorce drama they cannot possibly understand—‘Plenty shootem, no more kissem’ is their idea of a good programme—while waiting on the corner for a Don Jose from the unemployed camp strolls Carmen herself, with graceful swinging hips and flashing eyes. Romances of that silver sheet, open to the skies, are pale to the romance behind all those dark eyes watching.

But that is only one act. Out in the native compound, on a curve of beach a mile away, a hundred tribes are gathered in their season, foot-pilgrims of 2000 square miles of territory, never speaking nor mingling with each other in the tin lean-to and paperbark huts of the camp. All the week, in frocks and trousers, they perform the menial tasks of the latticed houses, but the walkabout of week-end finds them ‘noble and nude and antique,’ queer, savage figures painted with the vivid ochre stones of the seashore, hooshing in corroboree.

There is the football match of Saturday afternoon, with barrackers in twenty-five recognised languages and the ‘yacka-hoi’ of the tribes in all the unrecognised languages from Cocos Island to Thursday Island, with swarthy half-castes in bright blazers, the majority of the teams, leaping ten feet into the air to catch the shining, rain-wet ball, and running with the swift grace of a deer-hound. In the town of Upside Down, they play cricket in winter and football in summer, for one reason because it is cooler! From December to March the monsoon blows cold. A downpour of three inches in one shower is powerless to hold up the game, for what are rain-squalls to those who truly love the bounding ball? The game from a distance may appear more like water-polo, but to that motley crowd of 1000, only outwardly limp, it is good stuff.

All Darwin loves the football. It is the great democracy of Saturday afternoon. By diagonal tracks from Chinatown, motor-roads, bicycle trails, and blackfellow pads through the bush they come, wearing everything from red handkerchiefs only to the regalia of the Greek priesthood. The blacks occupy, by right of concession, the whole northern side of tie oval, where the lubras are pulling at their cutty pipes, the piccaninnies straddle-legged in the trees, and the wild myalls, after one glimpse, ready to hand over all the rain-stones and hair-belts in camp for somebody’s old cast-off blazer. A foul or a rough-house is greeted with hoots and shrill hooshings guaranteed to freeze the debil-debil off the face of creation, and when the bell rings ...

Table of contents

- FOREWORD

- BOOK I

- Book II

- Book III

- GLOSSARY

- INDEX