![]()

1 POTATO MOTHER

Omphalos

‘Those times when we grew gold, pure gold ...1

All 4,500 named varieties of potatoes trace their ancestry to the Americas. Wild potatoes grow along the American cordillera, the mountains that run from the Andes to Alaska. People living on its slopes have been eating potatoes for time out of mind. Stone tools and preserved potato peels show that wild potatoes were being prepared for food in southern Utah and southcentral Chile nearly thirteen thousand years ago; similar evidence dates their domestication from at least 7,800 BCE on the northern coast of Peru.2 They formed an important part of the diet of many of the cultures inhabiting the nine thousand kilometres between Utah and Chile. Together with foods such as quinoa and maize, they provided a robust, starchy backbone to cuisines also enriched with chile peppers, beans and other vegetables. Each variety can be propagated from a ‘mother potato’. She sounds like an ancient deity but in botany the term refers to the mundane tuber or seed potato that provides the genetic material from which additional plants are cultivated.

One difficulty with potatoes is that they are difficult to store. Anyone who has ever lost track of a bag of potatoes knows this. They have an unfortunate tendency to send forth a tangle of roots, and, worse, rot into a foul-smelling puddle. Andean peoples solved this problem by freeze-drying. Exposing potatoes to the intense cold of the high mountains transforms them into little fists of stone, immune to decay. The technique also neutralizes the poisonous glycoalkaloids present in some of the bitter varieties, allowing these to be eaten safely. If the potato-rocks are trampled underfoot like petrified grapes, it is possible to reduce them to a dry powder that lasts for years. This dried substance, chuño, captivated Spaniards when they first encountered it in the sixteenth century, and they invariably described in some detail how it is made. Europeans were however slow in adopting it themselves; it was left to industrial manufacturers in the twentieth century to bring us Smash and other commercially produced instant mashed potatoes.

Because potatoes were an essential part of the daily diet in the Andean world, their cultivation was a matter of importance. Various rituals helped ensure an abundant harvest. One account from sixteenth-century Peru describes the festivities that marked the inauguration of the planting season in the mountain village of Lampa. Local dignitaries seated themselves on carpets to watch the proceedings. A procession of richly attired attendants accompanied the seed potatoes, which were carried by six men making music on drums. Events culminated with the sacrifice of a particularly beautiful llama, whose blood was immediately sprinkled on the potatoes. Comparable practices (not necessarily involving llama blood) persist to the present day. Spanish priests objected strongly to these ceremonies but were often powerless to prevent them.3

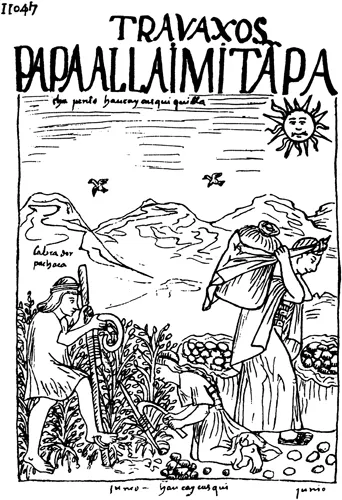

The Andean writer Felipe de Guaman Poma de Ayala described the agricultural potato cycle in an extraordinary manuscript that he composed in the early seventeenth century, after the arrival of Europeans. The son of indigenous nobility, Guaman Poma was born shortly after the Spanish conquest of his homeland. Late in his life he was moved to recount the history that he had to some extent witnessed first-hand. Guaman Poma’s New Chronicle, as he titled the thousand-page text, offered a universal history of the world, from Adam and Eve, through the Inca monarchs, to the dismal period of Spanish rule, whose multiple evils Guaman Poma documented in detail.4 It also described the ritual calendars of both Christian and Incaic religions, and the agricultural tasks carried out each month. The chronicle is illustrated lavishly with Guaman Poma’s idiosyncratic and immensely appealing line drawings. Several show the labour required to cultivate the essential potato. Digging sticks in hand, a man and woman weed the field in the picture for June, while a second woman ports a heavy sack away for storage. Other drawings depict men and women at work sowing seed potatoes and tending the abundant plants.

FIGURE 3 Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, June: Time of Digging up the Potatoes, ‘El primer nueva corónica y buen gobierno’, 1615–16. Potatoes were an essential foodstuff for Andean people. This seventeenth-century drawing by the self-taught Felipe Guaman Poma shows a potato harvest. By using digging sticks rather than ploughs farmers were able to cultivate very steep slopes, thereby making efficient use of the mountainous terrain. After the harvest some potatoes would have been freeze-dried so that they could be stored for a long time. GKS 2232 quarto, Det Kongelige Bibliotek, Copenhagen.

Unlike maize, which held a high status within the Inca state, potatoes were considered a lowly food, necessary but banal. Even in the potato’s omphalos they were viewed with some disdain. Along the Andes, maize was used to brew the all-important chicha or aqha, the corn beer that accompanied virtually every important political encounter. Potatoes played no comparable role in high diplomacy; for Andeans as for us, they were ordinary things. Guamon Poma contrasted the robust stature of maize eaters with puffy, effete villagers forced to subsist on dried chuño.

For these reasons, potatoes did not enjoy the intense state ritual lavished on the maize crop. The Inca himself participated every year in a symbolic maize-planting ceremony, to the accompaniment of music and song. Similar state-level festivities marked the maize harvest, and the intervening period was overseen by a team of priests who fasted throughout the planting season and kept track of the crop’s progress. In the sacred fields around the Inca capital, Cuzco, small gold replica cornstalks were interspersed among the growing maize, to ‘encourage’ it.5 No such imperial oversight was bestowed on potatoes. Cultivated a village level, they were traded and consumed within more local orbits, their growth fostered by smaller rituals such as the one that took place centuries ago in Lampa, where the sprinkling of llama blood on seed potatoes distressed the Catholic cleric.

All potatoes nonetheless benefitted from the attention of the Potato Mother, Axomama, daughter of the earth goddess Pachamama, and sister to Saramama, the Maize Mother. As these names suggest, Andean potato language and cosmology are rich in f eminine reproductive power. Plant breeders, perhaps unwittingly, replicate this vocabulary when they speak of the mother tubers from which all potato plants derive. Watching over the potato fields in the Andes – which scientists suggestively call the tuber’s ‘cradle area’ – Axomama cares for her tuberous offspring. Together with her sisters and their all-powerful mother, Axomama controls the earth’s fertility, overseeing the growth of potatoes and other things necessary for sustenance. Household shrines to Pachamama and her fertile daughters balanced state-level neglect of potatoes. The veneration of this feminine dynasty long pre-dated the official rituals of the Inca empire, and persists to the present.

For Andean farmers, human history and human bodies were entangled with these plants and the broader universe. Beautiful or unusual potatoes were themselves miniature Potato Mothers, and all encapsulated the generative powers of the female body. ‘Corn and clay, potatoes and gold were linked together as emblems of female powers of creation’, writes the historian Irene Silverblatt.6 Just as Abosch’s Potato 345 is at once a solid, earthly potato, an organic, living planet, and perhaps a human body, so a Potato Mother is the fecund mother plant used to breed up new generations of potatoes, and an ancient being in command of the earth’s powerful generative strength. Today Andean potato farmers coddle the skittish, feminine soil, hoping she’ll feel sweet enough to favour them with a good harvest. In the happier days before colonialism, they recall, ‘we grew gold, pure gold’: potatoes as golden nuggets, living stones.7

The Moche, who lived along the northern coast of Peru in the first millennium CE, formed beautiful ceramic containers in the shape of potatoes. Moche potters often created realistic replicas of ordinary foodstuffs such as potatoes, or squash or maize. At the same time as they represented the elements of the mundane kitchen world these clay recreations alluded to the overarching spiritual universe that made all existence possible. In the vessel shown in Figure 4, the four potatoes point to the four corners of the universe.8

FIGURE 4 Moche Stirrup Vessel, 100–800 CE. The Moche inhabited the northern coast of what is now Peru. They left behind many beautiful ceramic vessels, some depicting people, plants and animals, often with striking realism. The skilled ceramicist who shaped this container arrayed the four potatoes so that they point to the four cardinal directions of the universe. The pot is at once a realistic portrayal of an important Andean food, and an acknowledgement that agriculture, nourishment and life itself unfold within a larger cosmology. Museo Larco, Lima, Peru.

Alongside such lovely earthenware vegetables Moche potters crafted disturbing vessels that meld human faces disfigured by cuts and slashes, missing lips and noses, with the form of a potato. A strange, bulbous figure looks back at us from the pot in Figure 5, its body formed from lumpy tubers. Three eyes stare out from its belly. Lacking lips, it can only grimace with its unnaturally wide mouth.

Redcliffe Salaman, the author of a monumental history of the potato first published in 1949, developed the theory that these pots depict the unfortunate victims of Andean harvest rituals. Some people, he surmised, were selected to represent the potato harvest. The more ‘eyes’ a potato develops, the more shoots it sends out, which means it will produce more prolifically. Perhaps, in order to ensure a bountiful crop, these symbolic potato-people had additional eyes incised into their own bodies, or their lips excised to widen their mouths into another huge eye. Living Mr Potato Heads, their faces became potatoes – people and potatoes superimposed to reveal their unexpected commonalities. Anthropologists have questioned this interpretation, but that’s what I think of when viewing these strange pots. They remind us that the story connecting humans to potatoes is a tale of violence as well as sustenance.

FIGURE 5 Moche Vessel of a Potato with Anthropomorphized Head, 6–600 CE. Three bulbous tubers make up the body of an unhappy-looking creature with too many eyes and no proper mouth. What sort of being is this? The historian Redcliffe Salaman surmised that such vessels represent the people sacrificed to ensure a good potato harvest. Perhaps, he speculated, these victims had extra ‘eyes’ etched into their living faces, to encourage the seed potatoes to send forth many shoots. By excising their lips their mouths could be widened artificially into another sprouting eye, converting their bodies into symbolic potatoes. Ethnologisches Museum–Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, Stiftung Preußischer Kulturbesitz, and Claudia Obrocki (photographer).

The great hunger

‘And where potato diggers are you still smell the running sore.’9

In Ireland the connections between potatoes, people, sustenance and suffering run deep. The Great Famine of 1845 to 1848, which resulted in the death or emigration of a fifth of the population, marked Irish history. Potatoes arrived in Ireland in the sixteenth century, probably from Spain, and over the next centuries came to play an ever more important role in the diet of the Irish poor. The potato’s superlative power to convert earth and light into calories made it possible for entire families to live on the minute patches of land onto which the rural Irish were squeezed as commercial wheat, dairy and meat production expanded after the English colonized Ireland in the sixteenth century. By the 1840s some forty per cent of the population subsisted almost entirely on potatoes, or potatoes with a bit of buttermilk if they possessed enough land to pasture a milch cow. Poor men in rural Ireland ate between three and five kilos of potatoes a day and little else.10 The varieties grown were as limited as this diet. While a single valley in the ...