eBook - ePub

Conversations with Allende

Socialism in Chile

- 190 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

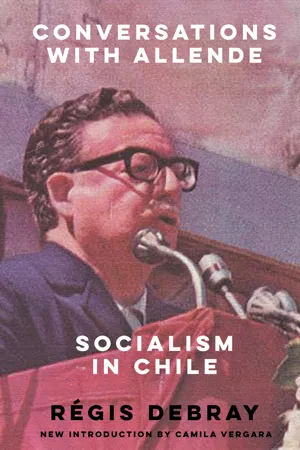

Conversations with Allende

Socialism in Chile

About this book

The election in Chile of the Marxist leader of the Socialist Party, Salvador Allende, to the presidency in October 1970 inaugurated a political situation unique in Latin America and of world-wide significance. Allende's Popular Unity coalition embraced Socialists and Communists and campaigned on an election programme of unprecedented radicalism - nothing less than the abolition of monopoly capitalism and imperialism in Chile. In this book, R?gis Debray, recently released from his Bolivian gaol, questioned President Allende about his strategy for socialism. These discussions ranged widely over the history of the workers' movement in Chile, the strength of imperialism in Latin America, the experience of the first months of the Allende government, the role of the Chilean armed forces, Allende's personal background and friendship with Che Guevara, the seizure of land by peasants since the Popular Unity victory, and the international outlook of the new Chile.

In an introductory essay, Debray furnished an analysis of Chilean history and politics which situated Allende in the past and present of the country and explored the dynamics of the class struggle now unfolding there. For this new anniversary edition, leading Chilean leftist scholar Camila Vergara has written a new introduction which appraises the book in the light of recent political developments in Chile.

In an introductory essay, Debray furnished an analysis of Chilean history and politics which situated Allende in the past and present of the country and explored the dynamics of the class struggle now unfolding there. For this new anniversary edition, leading Chilean leftist scholar Camila Vergara has written a new introduction which appraises the book in the light of recent political developments in Chile.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Conversations with Allende by Régis Debray, Ben Brewster, Peter Beglan, Ben Brewster,Peter Beglan in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & Political Biographies. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Conversations with Allende

This interview took place in two parts, the first in Santiago and the second in Valparaiso, the seat of government in summer, the Popular Government having transferred to this town on 6 January, on which day President Allende held a mass meeting in front of the Valparaiso Administrative Building.

I

Debray: Comrade President, does a man change when he is in power?

Allende: Well, Regis, people always used to call me ‘comrade Allende’ and now they say ‘comrade President’. Obviously, I’m aware of the responsibility that this implies.

Debray: Does a socialist militant change when he becomes Head of State?

Allende: No. I believe that the Head of State who is a socialist remains a socialist, but his actions must be consonant with reality.

Debray: It really is something new to find a socialist in power who still feels and acts as a socialist! There aren’t all that many examples of this, comrade.

Allende: I know, unfortunately this is true. Nor are there many socialist parties which are Marxist in the true meaning of the term.

Debray: And if we could go back a little in time; you were one of the founders of the Socialist Party?

Allende: Yes, I was.

Debray: That was about ’32…

Allende: 1933, to be exact.

Debray: What was the basis of your personal, political education? How did you come to join the Socialist Party?

Allende: I didn’t join the Socialist Party, Regis – I am a founder, one of the founders of the Socialist Party.

Debray: My question would be: ‘Why socialist rather than communist?’1*

Allende: Well now, when we founded the Socialist Party, the Communist Party already existed, but we analysed the situation in Chile, and we believed that there was a place for a Party which, while holding similar views in terms of philosophy and doctrine – a Marxist approach to the interpretation of history – would be a Party free of ties of an international nature. However, this did not mean that we would disavow proletarian internationalism.

Debray: I understand that there was a certain amount of sectarianism at the time …

Allende: You know quite well there was. The Communist Party was characteristically a closed, inward-looking party, and we believed that what was required was a party based, I repeat, on the same ideas, but which would have a much broader outlook, would be completely independent, and would adopt other tactics geared specifically to deal with the problems of Chile according to standards which are not dominated by international criteria.

Debray: I understand that the first socialist republic in Latin America lasted twelve days.

Allende: That’s all…

Debray: and this was in Chile …

Allende: Yes, in ’32.

Debray: Were you involved in it, or did the coup by Marmaduke Grove2 have an influence on the founding of the Party?

Allende: Influence? It had a tremendous influence.

Debray: Did you have problems afterwards?

Allende: During that period before 1932, I was sent down from the University. It was during the time known as the Ibañez dictatorship,3 which was certainly not typical of dictatorships in Latin American countries – in fact, one could say that it was a benign dictatorship, the outcome of a chaotic government and a chaotic economic situation, and, as generally happens, the student organizations had to stand up to the dictatorship. I took part in this, and for this reason I was sent down from the University and arrested.

Debray: Did they institute proceedings against you?

Allende: Yes. I was involved in five cases; I was tried by court-martial. When Marmaduke Grove’s Socialist Republic fell, I was a houseman in a hospital in Valparaiso, and made a speech as a student leader in the Faculty of Law, and as a result, was arrested. Other members of my family were also put in prison, including my brother-in-law, Marmaduke Grove’s brother, and one of my brothers who had virtually nothing at all to do with politics. As you can see, we had close family ties with Grove. On that occasion, we were tried by a court-martial which set us free. We were arrested again and put through another court-martial; then came the stage of the real trial. My father was unwell; he’d had a leg amputated and he had symptoms of gangrene in the other. In fact, he was dying, and my brother and I were allowed out of prison to go to see him. As a doctor, I realized just how serious his condition was. I was able to talk with him for a few minutes, and he managed to tell us that all he had to leave us was a clean, honest upbringing – he had no material wealth. He died the next day, and at his funeral I made the promise that I would dedicate my life to the social struggle, and I believe that I have fulfilled that promise.

Debray: There is something else I’m interested to know. I know that you are not a theoretician, but what one might call a firm conceptual foundation is apparent in your actions and speeches. So I wonder how you came to become a Marxist Leninist?

Allende: Well, the fact is that during my student days, I’m talking about ’26 and ’27 when I had just started reading medicine, we medical students were the most advanced.

Debray: Rather than the philosophers or ‘humanists’ in the Faculty of Letters?

Allende: Yes. The medical students were traditionally the most advanced. At that time, we lived in a very humble district, we practically lived with the people, most of us were from the provinces and those of us living in the same hostel used to meet at night for readings of Das Kapital, and Lenin, and also Trotsky.

Debray: It is said that this is where you differed from the Communist party comrades, in that they didn’t read Trotsky, I suppose.

Allende: Well, I believe that there are those who will tell you that the Communist Party would not read him, but there were no such barriers for us. I am well aware that there is no revolutionary action without revolutionary theory, but I am essentially a man of action. Since my student days I have always been in the front line of the struggle, and this has taught me a lot.

Debray: Yes, the University of Life, as they say; but books are another vital source of learning. A concrete question: Have you read Lenin’s State and Revolution?

Allende: Yes, of course.

Debray: Good, because we’ll probably discuss it a little later on.

Allende: In many of my speeches in Parliament, I have quoted passages from this work and earned criticism from the spokesmen of the reactionary press as a result. One such newspaper, El Mercurio, reproduced paragraphs from one of my speeches and from Lenin’s book as an illustration of my intention, naturally, to ‘suppress the bourgeois State’. I think that basic works like State and Revolution contain key ideas, but they can’t be used as a Catechism.

Debray: I’ve always heard that you’ve had connections with freemasonry and yet you are a Marxist; you know at one time there was a serious dispute within the international workers’ movement. For example, in France in the twenties, the freemasons were expelled from the Communist Party, which was then in its infancy. Do you see a contradiction between your supposed connections with freemasonry and your Marxist position, your class position?

Allende: First, Regis, let me remind you that the first Secretary General of the French Communist Party was a freemason.

Debray: Yes, yes …

Allende: And that it was only by the time of the Third International that incompatibility between the two movements was established.

Debray: Yes.

Allende: Now, from a personal point of view, I have a masonic background. My grandfather, Dr Allende Padín was a Most Serene Grand Master of the Masonic Order in the nineteenth century, when being a freemason meant being involved in a struggle. The Masonic Lodges and the Lautaro Lodges4 were the corner stone of independence and the struggle against Spain.

Debray: Bolivar and Sucre were freemasons.

Allende: Exactly. So you can understand perfectly well that, with this kind of family tradition, and again, since the masonic movement fought for fundamental principles like Liberty, Equality and Fraternity, one can viably have such connections. Now I have maintained within the masonic movement that there cannot be equality in the capitalist regime, not even equality of opportunity, of course; that there cannot be fraternity while there is class exploitation, and that true liberty is a concrete and not an abstract notion. So you see I interpret the principles of freemasonry according to their true content. Now, I know perfectly well that there are countries where freemasonry could not be considered consistent with these principles.

Debray: Comrade President, you come from a fairly well-off family, one might say a bourgeois family …

Allende: In orthodox terms, yes, my origins are bourgeois, but I would add that my family was not associated with the economically powerful sector of the bourgeoisie, since my parents were members of what are known as the liberal professions, as were my mother’s family.

Debray: And where did they stand politically?

Allende: In Chile the struggle against conservatism was very violent during the last century, and it was fought out on a religious front. The conservatives opposed all progressive moves, such as the establishment of lay education. All my uncles and my father were Radical Party5 militants at a time when being a radical meant that one held advanced views. My grandfather founded the first lay school in Chile and his political views earned him the nickname of ‘Red Allende’.

Debray: And since then …

Allende: Since then the family has maintained the tradition.

Debray: So family tradition could have influenced your upbringing. Do you remember any other kinds of influence?

Allende: When I was a boy of about fourteen or fifteen, I used to hang around the shop of a shoemaker, an anarchist called Juan Demarchi, to hear him talk and exchange views with him. That was in Valparaiso at the time when I was at grammar school. After the school day, I used to go and converse with this anarchist, who was a great influence on my life as a boy. He was sixty or perhaps sixty-three and he was quite happy to talk with me. He taught me how to play chess, he spoke to me of the things of life, and he lent me books…

Debray: Which books?

Allende: All the essentially theoretical works, so to speak, like Bakunin, for example, but the most important thing was Demarchi’s commentaries because I didn’t have the temperament for reading in depth; he explained things to me with the simplicity and clarity that one finds in self-taught workers.

Debray: I see. And afterwards, you embarked on your political career. You were a Member of the Chamber of Deputies?

Allende: Yes, but first I began medical studies. I was a student leader and afterwards, in order to be able to work in the hospitals in Valparaiso, I had to take four examinations and although I was the only candidate, I was rejected because of what I had been as a student. I started to work as a pathology assistant, and that means that my first job was very hard and very dull. I had to carry out autopsies. Still in Valparaiso, in spite of my work, I engaged in militant activities and I was practically the founder of the Party in Valparaiso. I went into the hills and the suburbs, and out into the country …

Debray: So that when you return to Valparaiso, you feel at home there.

Allende: Look, I’ve always said this, my political career began in Valparaiso, I’m a native of this town, and I’m the first President from Valparaiso.

Debray: I understand that after being elected Deputy for Valparaiso, you became a Minister in the Popular Front6 at a very early age.

Allende: Indeed. At thirty, I was a Minister under Pedro Aguirre Cerda. Look, that’s Don Pedro in this photo; he was a man of great human qualities, a very kind man and interestingly enough, his contact with the people had the effect of bringing him round to an increasingly radical position. To begin with, he was the bourgeois-radical politician ‘par excellence’ and, in response to the loyalty and affection of the people, he was gradually transformed into a man of deeper conviction, much closer to the aspirations of the people, but he never ceased to be a Radical and never wished to be anything other than a Radical. That was at the time of the Popular Front; at that time, then, although it is true that there were the same Parties as today, the Radical Party, the party of the bourgeoisie, was the dominant party, and this is what makes the difference between the Popular Unity today and the Popular Front: in the Popular Unity, no party enjoys a position of supremacy, but there is a supreme class, the working class, and there is a Marxist Socialist President.

Debray: Afterwards, you continued in Congress and rose to become President of the Senate in the last years. How is it that a man from the petty bourgeoisie – with all those parliamentary, masonic, ideological and social ties – can carry out a consistently revolutionary line of action? Having been associated with many bourgeois institutions, the most representative of the regime into the bargain, how have you managed to become a leader of the masses, the prime mover of a process aimed at revolution.

Allende: I have often thought about this question. First, there is an intellectual commitment in youth, and later there is the real commitment with the people. I am a Party man and I have always worked with the masses. I am aware of being a grass roots Chilean politician and very close to the people. Remember, Regis, a great majority of revolutionary leaders have been drawn from the ranks of the middle and lower middle classes. Some, although they hadn’t suffered the effects of exploitation personally, understood and felt what it was, they realized its implications and came down on the side of the exploited against the exploiters. I have always brought my political standpoint to bear on those institutions you have enumerated, and this standpoint has always been representative of the people’s desires for social justice, and this is precisely what I’m doing now.

Debray: Good, let’s move on to something else. Comrade President, you are now 62.

Allende: Yes, 62 well-filled years.

Debray: You belong to a generation, shall we say the generation of Betancourt, Haya de la Torre, Arevalo and their peers.7 This generation is politically dead today. They are now a part of Latin American pre-history, and yet you are a central figure in its contemporary history, and will influence its future. Why were they left by the wayside, whereas you have continued to make progress?

Allende: Look, what you say is rather hard, but true enough. The truth is as follows: when it had been in existence for two or three years, the Socialist Party called a Conference of the popular parties of Latin America here in Chile. On that occasion, there were representatives of APRA7 and other populist movements, but there was already a noticeable difference, because the Socialist Party was a Marxist party, and we were categorically anti-imperialist; at the time, APRA also claimed to be an anti-imperialist party. The truth is sad. What happened? When the popular parties, for instance ‘Democratic Action’,7 came to power in Venezuela, they lacked the positive approach required to make the necessary changes, there was no struggle to change the regime, the system – on the contrary they threw in their lot with imperialism. APRA, for example, has not come to power, but in its attempt to do so, it has modified, mitigated and changed its attitude to imperialism. As a result, these parties have been overtaken by history and do not represent or interpret the aspirations of the Latin-American peoples.

Debray: You knew many of these leaders personally.

Allende: Yes, all of them. Betancourt, for example, lived in Chile; I was Minister of Public Health under...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction

- Conversations with Allende

- Notes

- Appendix