- 208 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

From Marxism to Post-Marxism?

About this book

A comprehensive history of the development of Marxist theory and the parameters of 21st-century politics

In this pithy and panoramic work - both stimulating for the specialist and the accessible to the general reader - one of the world's leading social theorists, G?ran Therborn, traces the trajectory of Marxism in the twentieth century and anticipates its legacy for radical thought in the twenty-first.

In this pithy and panoramic work - both stimulating for the specialist and the accessible to the general reader - one of the world's leading social theorists, G?ran Therborn, traces the trajectory of Marxism in the twentieth century and anticipates its legacy for radical thought in the twenty-first.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access From Marxism to Post-Marxism? by Göran Therborn in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Política y relaciones internacionales & Filosofía política. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Into the Twenty-first Century:

The New Parameters

of Global Politics

Politics is thought and fought out, policies are forged and implemented, political ideas wax and wane – all within a global space. The space itself decides nothing: only actors and their actions can do that. But it is this dimension – long global, in many respects, but now far denser in its worldwide connectivity – that endows these actors with their strengths and weaknesses, constraints and opportunities. Space provides the coordinates of their political moves. Skill and responsibility in the art of politics, luck and genius – and their opposites – remain constant, but it is the space that largely allocates the political actors their cards.

This global space comprises three major planes. One is socio-economic, laying out the preconditions for the social and economic orientation of politics – in other words, for Left and Right. Another is cultural, with its prevailing patterns of beliefs and identities and the principal means of communication. The third is geopolitical, providing the power parameters for confrontations between and against states. This chapter aims to map the social space of Left–Right politics, from the 1960s to the first decade of the twenty-first century. It is neither a political history nor a strategic programme, although it bears some relevance to both. It is an attempt to assess the strengths and weaknesses of the forces of Left and Right, in a broad, non-partisan sense – both during the recent past, which still bears forcefully on the present, and within emerging currents.

The overall geopolitical space will be invoked only where it most directly affects Left–Right politics. As regards the underlying conceptions, however, a few points of clarification may be needed. The analytical distinction between the two elements does not, of course, imply that they are literally distinct. In the concrete world, social and geopolitical spaces are conjoined. Nevertheless, it is important not to confound the two. The Cold War, for example, had an important Left–Right dimension – that of competing socialist and capitalist modernities. But it also had a specifically geopolitical dynamic, which pitted the two global superpowers against each other and entrained, on each side, allies, clients and friends. Which of these two dimensions was the more important remains a controversial question.

The resources, opportunities and options of interterritorial actors within the geopolitical plane are generated by a variety of factors – military might, demographic weight, economic power and geographical location, among others. For the understanding of Left–Right politics that concerns us here, two further aspects are particularly significant: the distribution of geopolitical power in the world, and the social character of interterritorial, or transterritorial, actors.

On the first, we should note that the distribution of power has changed dramatically during the last forty years, and not just in one direction. The period began with the build-up to the United States’ first military defeat in its history, in Vietnam, and with the ascendancy of the USSR to approximate military parity. Then came the collapse of the Soviet Union, and the US claim to a final victory in the Cold War. Although in 1956, the fiasco of the French–British-Israeli invasion of Suez signalled the end of European military might on a world scale, Europe has – as the EU – returned as both an economic great power and a continental laboratory for complex, interstate relations. At the beginning of the period, Japan was the world’s rising economic star; currently it is fading economically and rapidly ageing socially. By contrast, China’s still unbroken decades of spectacular growth have given economic muscle to its massive demographic weight.

The social character of interterritorial actors can be read not only from the colour of state regimes but also from the orientation and weight of non-state forces. Two new kinds of international actors – of divergent social significance – have become increasingly important during this period.1 The first consists of transnational interstate organizations such as the World Bank, the IMF and the WTO, which have jointly served as a major neoliberal spearhead for the Right (although the World Bank has had some dissenting voices). The second is a looser set of transnational networks, movements and lobbies for global concerns that have emerged as fairly significant, progressive actors within the world arena – initially through their links with such UN mechanisms as the human rights conventions and major international conferences on women and on population, and, more recently, through their international mobilizations against trade liberalization.

In brief, even though the US has become the only superpower, the geopolitical space has not simply become unipolar; instead, it has begun to assume new forms of complexity.

STATES, MARKETS, AND SOCIAL PATTERNINGS

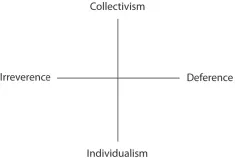

The social space of modern politics has at least three crucial parameters: states, markets and ‘social patternings’.2 The first two are well-known and highly visible institutional complexes. The third may require some explanation. It refers to the shaping of social actors – a process influenced, of course, by states and markets, but with additional force of its own, derived from forms of livelihood and residence, religions and family institutions. It involves not only a class structure but, more fundamentally, a rendering of variable ‘classness’. It may be useful here to invoke a more abstract, analytical differentiation of social patterning than the conventional ones of class size or strength, or of categorical identities such as class, gender and ethnicity. The patternings I want to highlight are sociocultural ones, with an emphasis on broad, socially determined cultural orientations rather than just structural categories. Here I suggest irreverence–deference and collectivism–individualism as key dimensions (sketched in Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Crucial dimensions of the social patterning of actors

Irreverence and deference here refer to orientations towards existing inequalities of power, wealth and status; collectivism and individualism to propensities – high or low – towards collective identification and organization. The classical Left was driven by the ‘irreverent collectivism’ of the socialist working-class and anti-imperialist movements, while other contemporary radical currents – for women’s rights or human rights, for instance – have a more individualist character. The traditional Right was institutionally, or clientistically, collectivist; liberalism, both old and new, tends rather towards ‘deferential individualism’ – deferring to those of supposedly superior status, entrepreneurial bosses, the rich, managers, experts (in particular, liberal economists) – and, at least until recently, male chefs de famille, imperial rulers and representatives of Herrenvolk empires.

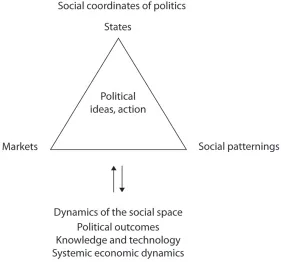

It is within this triangle of states, markets and social patternings that political ideas gain their ascendancy, and political action occurs. The dynamics of this space derive, firstly, from the outcomes of previous political contests; secondly, from the input of new knowledge and technology; and thirdly, from the processes of the economic system – capitalism and, formerly, actually existing socialism. A schematization of the full model is given in Figure 1.2.

Figure 1.2: Social space of politics and its dynamics

State Forms, Corporations, Markets

Most contemporary discussions of the state, whether from Left or Right, focus on the question of ‘the nation-state’ as it confronts globalization, or on privatization as a challenge to its institutions. These approaches tend to ignore both the reality of contemporary state policy-making and, even more importantly, the varying structural forms of state development. On the first point, the key question is: has the state’s capacity to pursue policy targets actually diminished over the past four decades? The clear answer for developed democracies is that, generally speaking, it has not. On the contrary, one could say that recent years have seen some stunning successes for state policies: the worldwide reduction – indeed, the virtual abolition – of inflation is one major example; the development of strong regional interstate organizations – the EU, ASEAN, Mercosur and NAFTA – is another. True, the persistence of mass unemployment in the EU is a clear policy failure, but the European unemployed have, on the whole, not been pushed into American-style poverty, which must count as at least a modest success.

Policy orientations and priorities have changed; new skills and greater flexibility may be required; as always, a considerable number of policies fail to reach their goals. But this is nothing new. Nation-states, regions and cities will differ, as always, in their effectiveness, but I see no trend towards a generally diminished policy-making capacity. That certain left-wing policies have become more difficult to implement is probably true, but that derives not so much from state-level failures as from the right-wing tilt of the political coordinates.

Successful State Forms

The most serious flaw of conventional globalization discourse, however, is its blindness to the development of strongly differentiated state forms over the past forty years. Two models arose in the sixties: the welfare state, based on generous, publicly financed social entitlements, and the East Asian ‘outward development’ model. Both have been successfully deployed and consolidated ever since. The core region of welfare statism has been Western Europe, where it has had an impact on all the original OECD countries. Although its European roots go back a long way, it was in the years after 1960 that welfare statism began to soar – in about a decade, the expenditure and revenue of the state suddenly expanded, more than during its entire previous history. Unnoticed by conventional globalization theory, the last four decades of the twentieth century saw the developed states grow at a far greater rate than international trade. For the old OECD as a whole, public expenditure as a proportion of GDP increased by 13 percentage points between 1960 and 1999, while exports grew 11 per cent.3 For the fifteen members of the European Union, the corresponding figures were 18–19 percentage points and 14 per cent.4

Despite the many claims to the contrary – echoed on both Left and Right – the welfare state still stands tall wherever it was constructed. Whether measured by public expenditure or by revenue, the public sector in the richest countries of the world stands at, or has plateaued at, peak historical levels. For the OECD countries of Western Europe, North America, Japan and Oceania, the national average of total government outlays (unweighted by population, but exclusive of Iceland and Luxembourg) in 1960 was 24.7 per cent of GDP. By 2005 it stood at 44 per cent. For the G7, public outlays increased from 28 per cent of their total combined GDP in 1960 to 44 per cent in 2005. True, the expenditure share in both cases was a couple of percentage points higher during the recession years of the early nineties than at the booming end of the decade, but that should be interpreted as a largely conjunctural oscillation. In terms of taxes, in 2006 the OECD beat its own historical record of tax revenue, from 2000, and registered its highest revenue ever, about 37 per cent of GDP flowing into public coffers. This is not to argue that there is not a growing need and demand for education, health and social services, and retirement income, which will require the further growth of the welfare state, a growth currently stultified by right-wing forces.

The second new state form – its breakthrough again coming in the sixties (following a pre-war take-off in Japan) – has been that of the East Asian outward-development model: oriented towards exports to the world market, biased towards heavy manufacturing, characterized by state planning and control of banks and credit, and indeed, sometimes, as in Korea, by full state ownership. Pioneered by Japan, the development state soon became – with varying combinations of state intervention and capitalist enterprise – a regional model, with South Korea (perhaps now the archetype), Taiwan, Singapore and Hong Kong blazing the trail for Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia and, less successfully, the Philippines (the latter, culturally and socially, is something of a Latin America in Southeast Asia, with its powerful landowning oligarchy still in place, for instance). These were the examples that China would draw upon from the late seventies onward; as, a decade later, would Vietnam. There is considerable variation between these states and their differing forms of capitalism but all arose within a common regional context – a Cold War frontier receiving a great deal of US economic (and military) assistance. All shared several features: Japan as the regional development model, a broken, or absent, landed oligarchy; a high rate of literacy; a strong entrepreneurial stratum, usually diaspora Chinese. For the most part, they have also had similar political regimes: authoritarian yet strongly committed to national economic development through international competitiveness, with the will to implement decisive state initiatives.

This sixties legacy remains a major feature of the world today. China, the largest country on the planet, has become history’s most successful development state, with a twenty-year growth rate per capita of almost 10 per cent per year. The crisis of 1997–98 hit Korea and Southeast Asia pretty hard but, with the possible exception of strife-torn Indonesia, it did not result in a lost decade. On the contrary, most countries – Korea above all – have already vigorously bounced back.

The Western European welfarist and East Asian development states were rooted in very differently patterned societies, and their political priorities have been quite distinct. But qua states, and economies, they have had two important features in common. Firstly, they are both outward looking, dependent on exports to the world market. Contrary to conventional opinion, there has been a significant, and consistent, positive correlation between world-market dependence and social-rights munificence among the rich OECD countries: the more dependent a country is on exports, the greater its social generosity.5 Secondly, for all their competitive edge and receptivity to the new, neither the welfarist nor the development states are wide open to the winds of the world market. Both models have established, and continue to maintain, systems of domestic protection. Among the welfare states, this takes the form of social security and income redistribution. When Finland, for instance, was hit by recession in the early nineties, with a 10 per cent decline of GDP and unemployment climbing to nearly 20 per cent, the state stepped in to prevent any increase in poverty, thereby maintaining one of the most egalitarian income distributions in the world. While I am writing this, the Finnish economy is riding high again, and Finnish Nokia currently reigns as the world leader in mobile phones. By European standards, the Canadian welfare state is not particularly developed; nevertheless, despite Canada’s close ties with its massive neighbour – reinforced through NAFTA – it has been able to maintain its more egalitarian income distribution over the past twenty years, whereas US inequality has risen sharply.

The Asian development states have been more concerned with political and cultural protection against unwanted foreign influences, often adopting an authoritarian nationalist stance. Japan and South Korea have waged low-key but tenacious and effective battles against incoming foreign investment. The IMF and, behind it, the US attempt to use the East Asian crisis of 1997–98 to force open the region’s economies has met with only modest success; Malaysia even managed to get away with imposing a set of controls on transborder capital flows.

State Failures

On the other hand, there has been a lethal crisis among economically inward-looking, low-trade states. The shielded Communist models have imploded, with the exception of North Korea, which barely remains afloat. China, Vietnam, Cambodia and Laos have all staked out a new course: China now has a proportionately larger block of foreign investment than Latin America. Cuba has managed to survive despite the US blockade – even after the disappearance of the Soviet Union – largely through mutating into a tourist destination, with the help of capital from Italy, Canada and Spain (although that capital is currently being overtaken by Venezuelan money in return for Cuban educational and medical aid). In Africa, the postcolonial states with national ‘socialist’ ambitions have failed miserably, through a lack of both administrative and economic competence and a suitable national political culture. South Asia had better initial conditions, with a qualified administrative elite, a significant domestic bourgeoisie and a democratic culture. But the outcome has been disappointing, with an exclusionary education system and low economic growth leading to an increase in the numbers of people living in poverty. Even after India’s recent moves onto a path of economic growth, it remains the largest poorhouse on earth. About 40 per cent of the world’s poor (living on less than $2 a day) are in South Asia, 75–80 per cent of the regional population. The turn towards import-substituting industrialization in Latin America in the fifties was not without success, especially in Brazil. But it was clear by the seventies and eighties that the model had reached a dead end. By then, the entire region had run into a deep crisis, economic as well as political. Traditionalist, inward-oriented states such as Franco’s Spain were also forced to change: beginning in about 1960, Spain took a new tack, concentrating on mass tourism and attracting foreign investment.

The widespread crises faced by this type of inward-looking state, in all its many incarnations – in sharp contrast to the successes of the different versions of the two outward-looking state forms – must have some general explanation. It should probably be sought along the following lines. The period after the Second World War saw a new upturn in international trade – although by the early seventies, it had only reached the same proportion of world trade as that of 1913. More important than its scale, however, was its changing character. As became clear by the end of the twentieth century, international trade has been decreasingly an exchange of raw materials against industrial commodities – predominant in the Latin American age of export orientation – and increasingly a competition among industrial enterprises. One effect of this growth of intra-industrial trade has been a great boost to technology; thus, countries standing aside from the world market have tended to miss out on this wave of development. By the early eighties, when the USSR finally managed to surpass the US in steel production, steel...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Introduction: Our Time and the Age of Marx

- 1. Into the Twenty-first Century: The New Parameters of Global Politics

- 2. Twentieth-Century Marxism and the Dialectics of Modernity

- 3. After Dialectics: Radical Social Theory in the North at the Dawn of the Twenty-first Century

- Notes

- Index