- 320 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

About this book

"They demolish our houses while we build theirs." This is how a Palestinian stonemason, in line at a checkpoint outside a Jerusalem suburb, described his life to Andrew Ross. Palestinian "stone men", utilizing some of the best quality dolomitic limestone deposits in the world and drawing on generations of artisanal knowledge, have built almost every state in the Middle East except their own. Today the business of quarrying, cutting, fabrication, and dressing is Palestine's largest employer and generator of revenue, supplying the construction industry in Israel, along with other Middle East countries and even more overseas.

Drawing on hundreds of interviews in Palestine and Israel, Ross's engrossing, surprising, and gracefully written story of this fascinating, ancient trade shows how the stones of Palestine, and Palestinian labor, have been used to build out the state of Israel-in the process, constructing "facts on the ground"--even while the industry is central to Palestinians' own efforts to erect bulwarks against the Occupation. For decades, the hands that built Israel's houses, schools, offices, bridges, and even its separation barriers have been Palestinian. Looking at the Palestine-Israel conflict in a new light, this book asks how this record of achievement and labor can be recognized.

Drawing on hundreds of interviews in Palestine and Israel, Ross's engrossing, surprising, and gracefully written story of this fascinating, ancient trade shows how the stones of Palestine, and Palestinian labor, have been used to build out the state of Israel-in the process, constructing "facts on the ground"--even while the industry is central to Palestinians' own efforts to erect bulwarks against the Occupation. For decades, the hands that built Israel's houses, schools, offices, bridges, and even its separation barriers have been Palestinian. Looking at the Palestine-Israel conflict in a new light, this book asks how this record of achievement and labor can be recognized.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Stone Men by Andrew Ross in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Archaeology. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

1

Conquest and Manpower

In Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants of the country … The Four Great Powers are committed to Zionism. And Zionism, be it right or wrong, good or bad, is rooted in age-long traditions, in present needs, in future hopes, of far profounder import than the desires and prejudices of the 700,000 Arabs who now inhabit that ancient land.

—Lord Arthur Balfour, Memorandum to Lord Curzon, August 11, 1919

Mapai [the Israeli Labor Party] holds the orthodox Socialist view concerning “imperialism,” which it regards as something inherently evil. It might therefore have been expected to be an ally of the Arab workers in their struggle against British “imperialism.” This is however not so, because its Zionism, on all occasions, takes precedence over its socialism.

—George Mansour, “The Arab Worker under the Palestine Mandate,” 1937

In many parts of the world, the grisly upshot of settler colonialism was the (near) eradication of indigenous populations.1 Zionist settlement of Palestinian lands might have been little different had it not proceeded at a time when the great empires of the modern era were winding down and cracking apart. The Israeli land grabs of 1948 and 1967 ran directly against the headwinds of decolonization elsewhere in the region and the world. Subsequent Israeli treatment of Palestinian refugees and occupied peoples fell afoul of canons of international law that had pivoted away from supporting the European doctrines of conquest. For those and other reasons, Zionist colonists were unable to forcibly transfer all of the inhabitants of Palestine in line with what Zionist founder Theodor Herzl described as the need “to spirit the penniless population across the border … whilst denying it any employment in our own country.”2 In 1937, David Ben-Gurion wrote that “I support compulsory transfer. I don’t see anything immoral in it,”3 and Joseph Weitz, the director of the Jewish Agency’s Land Department, spelled it out:

The only way is to transfer the Arabs from here to neighboring countries, all of them except perhaps Bethlehem, Nazareth and Old Jerusalem. Not a single village or a single tribe must be left.4

After 1948, when they attained an unassailable demographic advantage (Ben-Gurion aimed for an 80 percent Jewish majority), Israeli leaders opted for hardship policies often referred to as “soft transfer” or “silent expulsions” (in which Palestinians would self-deport) or more varied forms of ethnic cleansing such as settlement expansion on confiscated land. At the same time as the settlers took over lands, they commandeered the labor of indigenous Arabs to build the settler state. These two developments were not unconnected. Turning rural male Palestinians into wage workers—as kibbutz field hands, tilers and plasterers on Israeli construction sites, or all-purpose laborers on West Bank settlements—meant that their hold on the land was weakened, making it easier to seize.5 But long before settlers gained the upper hand as employers and occupiers, they had to compete for, and win, a decisive share of the labor market—a story that began in scrappy fashion in Ottoman Palestine, generated no end of friction during the British Mandate, and reached its bloody climax in 1948.

Those early labor market conflicts cast the die that would shape the future career of apartheid-style segregation in Israel/Palestine.6 They also determined how control of the Palestinian workforce, after 1948 and 1967 and to this day, became the key to the building out of the Israeli state and its expansion into the West Bank. That is why, in planning how to write this book, I realized I would need to review the history of employment in early twentieth century Palestine and to do so through the lens of the construction jobs that are my primary interest in these pages. In the first three formative decades of the century, the often bitter contention over jobs and livelihoods fueled the steady growth of both Zionist and Palestinian nationalism. The outcome was violent and unequal; after the Nakba, it bred a cruel dominion, and later an occupation, that continues to violate international norms and laws. But the version of that history which I will present in this chapter shows that in spite of the early settler resolve to “purify” workplaces as exclusively Jewish, or the later government efforts to replace Palestinians with migrant workers, the physical unfolding of Zionism on the land has always been a project that both relied on Arab workers and was indebted to them in ways that have yet to be fully reckoned with.

A European Wage in the Middle East

Because of my own point of entry sketched earlier (see the Preface), I chose to begin with the founding of Kibbutz Ginosar itself, as a tactical Zionist outpost, in the heat of the anti-colonial Arab Revolt (1936–39). In common with other rudimentary settlements established in the Eastern Galilee during this period, the founders of Ginosar intended to secure a Jewish presence on militarily strategic portions of Arab territory. But the other goal behind their formation was to carve out a sustainable Jewish niche in the labor market, where previous efforts at agricultural settlement had failed.

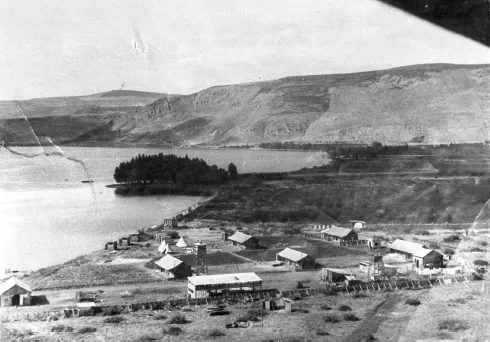

In 1934, Ginosar’s young founders struck camp in the Jewish settlement at Migdal (just outside the village of Majdal, allegedly the birthplace of Mary Magdalene), on a ridge overlooking the western shore of the Sea of Galilee. There they awaited allocation from the Jewish Agency, the leading Zionist organization, which had teamed up with the Jewish National Fund (JNF) to buy Arab land from absentee landlords. In March 1937, when the paramilitary Haganah command encouraged them to secure the strategic road between Tiberias and Rosh Pina, the group moved down on to the traditional lands of Ghuwayr Abu Shusha (the Arabic name for Ginosar’s location) to occupy a portion of the 5,000 dunums (a dunum is a quarter acre) that had been purchased by JNF rival, Baron Edmond de Rothschild’s Palestine Jewish Colonization Association.7 Once in place, they hastily erected a “tower and stockade” (homa umigdal). Thrown up overnight to outfox the British authorities, this kind of fortification—a watchtower and four shacks, surrounded by a gravel-filled wall and a barbed-wire perimeter fence—was utilized by dozens of start-up kibbutzim during this period.8 Under Ottoman law (adopted by the British), an illegal building could not be demolished once a roof was added; hence the hurried nocturnal effort to raise up a structure, no matter how rickety.9

Courtesy of Kibbutz Ginosar

Ginosar pioneers in settler guard uniforms, with watchtower, 1937.

Once the stockade was in place, and after the Arab Revolt was brutally suppressed by the British (with Zionist paramilitary assistance), the Ginosar group dug in and expanded its holdings, though only after a violent conflict over water rights with the neighboring Ghuwayr Abu Shusha villagers (which resulted in two Arab fatalities and the subsequent imprisonment of ten kibbutz members).10

Many of these founder members, who included Yigal Allon, freshly graduated from Kadoorie Agricultural High School, were ardent disciples of A. D. Gordon, a prominent advocate of the Labor Zionist doctrine that would become a dominant strain among other Yishuv leaders like Ben-Gurion, Yosef Brenner, Golda Meir, and Berl Katznelson. In accord with Gordon’s teachings, these pioneers believed that true possession of land was something that had to be earned, not through forcible acquisition, but through their labor with the soil. For this kind of Zionist, manual work was hallowed as an act of individual redemption, and this labor was an anvil on which to forge the self-reliant mentality of Jewish nationalism. Yet Ginosar, like other kibbutzim, would get an economic boost from the annexation of stolen land. During the Nakba, the kibbutzniks took over neighboring Arab lands in Ghuwayr Abu Shusha, whose residents were expelled as part of Yigal Allon’s Operation Broom.11

Courtesy of Kibbutz Ginosar

Aerial view of Ginosar stockade, 1937.

A charismatic zealot, Gordon had settled in Degania (the first kvutza, a kibbutz prototype), ten miles to the south of Ginosar, in 1919, and his influence grew considerably through the Gordonia and Hapoel Hatzair (Young Worker) movements in the decade following his death three years later. His teachings were a cocktail of Tolstoyan communalism, Jewish mysticism, and neo-Marxist productivism, but his assertions about Zionism were often disarmingly candid:

we come to our Homeland in order to be planted in our natural soil from which we have been uprooted, to strike our roots deep into its life-giving substances, and to stretch out our branches in the sustaining and creating air and sunlight of the Homeland.12

Gordon’s views were aligned with formative Labor Zionists like Ber Borochov (buried in the Kinneret cemetery, also just to the south of Ginosar), who argued that, historically, Jews had seldom been allowed to occupy productive positions in society, either as artisans or farmers, but had been relegated to middlemen occupations in trade, finance, and services. Settlement in Palestine held out the promise of a Jewish peasant-proletarian nation, with agrarian roots, and a producer base in control of its economic and spiritual destiny. To fulfil this aspiration, Gordon and other Labor Zionists tried (with only partial success) to steer their acolytes away from the kind of urban proletarian identity advocated by other European socialists and onto the redeeming land itself.

Gordon allegedly coined the slogan of “Conquest of Labor” to evoke the personal struggle of Zionist settlers, through manual toil on the land, to bring forth the muscular personality of the New Jew.13 In practice, the term became inseparable from the concept of “Hebrew Labor,” which he and others took up as the rallying cry for barring Arabs from employment in Jewish enterprises. Nor can the darker meaning of Gordon’s “conquest” be ignored when put in the context of colonial settlement. Who was being conquered? Gordon’s deferential “inner Jew,” deprived, by generations of Gentiles, of the right to serve as the natural backbone of the economy? Or the Arab fellahin peasantry, many of them already struggling as indebted tenant-farmers, who would be chased off these lands and their own ancestral small holdings in the years to come? Gordon’s “religion of labor” was a powerful motivator for the partisan mentality of kibbutzniks who imagined they were building an agrarian socialist paradise. But it was also a convenient, and increasingly unsubtle, fig leaf for the land colonization project of Zionism.

In some respects, Gordon’s creed had a clear affinity with Locke’s labor theory of property, and, although they acquired their early colonies through market land purchases, Zionist settlers increasingly promoted their cause through the widely circulated mythology about the “barren wasteland” of Ottoman Palestine and the settlers’ vaunted success in “making the desert bloom.” Just as in North America, the settlers often intruded on precapitalist systems of land commons. In Palestine, these were either miri, or state-owned, land where grazing and growing rights were granted by usufruct to peasants, or the more egalitarian musha (accounting for 50 percent of land ownership in Palestine), a communal form of production that evenly shared out the fertile and poor lands through periodic redivision among village clans.14

Socialist settlers with modest, assimilationist goals might have adapted to, and flourished within, these systems, but Jewish agricultural settlement was increasingly driven along a narrower, nationalist track and would be steered ultimately toward maximal control of territory, interpreted as a claim of ancient right on the Land of Israel (Eretz Israel). Initially, however, the collective enterprise of the kibbutz presented a technical solution to the economic challenge faced by Jewish settlers in Palestine since the 1880s—how to generate a “European standard of living” from a Middle Eastern agricultural livelihood.

In the late nineteenth century, early Jewish colonists (the “Lovers of Zion” from Eastern Europe) tried, and failed, to subsist on lands near the coast and in Eastern Galilee that had been purchased from absentee owners residing in Damascus, Aleppo, and Beirut. Baron Edmond de Rothschild converted these colonies into cash-cropping plantations, drawing on the colonial Algerian model and aimed at the international export market. This was a labor-intensive system, and Rothschild found the cost of employing Jewish settlers with little agrarian experience to be prohibitive, given the abundant availability of Arabs with unmatchable skills in regional agriculture and with low-cost household economies of their own.

After Rothschild turned over the titles of these colonies to the Palestine Jewish Colonization Association in 1898, a new wave of planters were allowed to establish privately owned moshava farms, but they too favored the cheaper and more capable Arab hands. Jewish workers appealed to these new owners to employ them on the basis of shared ethnicity and at higher pay, arguing that it was unjust to reduce Jews to Arab standards of living, but the planters would not do so unless they worked for an “Arab wage,” to be topped up from international Zionist funds. None of these agricultural efforts to employ the Jewish settlers succeeded in providing year-round livelihoods, and so large numbers of them left the region.15

Another doomed effort to create a sustainable Jewish workforce involved the importation of Yemenite Jews from 1909 to 1914 to take the low-skill agricultural jobs, again at “Arab pay.” Affronted by being physically segregated and consigned, like a lower caste, to the more routine tasks, the Yemenites resisted and ended up competing for the better, higher paid jobs that were reserved for Ashkenazis.16 In some respects, the unequal economic status of Israel’s Mizrahi Jews (Arabic-speaking and from Arab cultural backgrounds) originated in this early conflict and has endured to the present in the form of a gap in income and status between Mizrahi and Ashkenazi populations. The long-standing social and cultural denigration of these “Oriental Jews” in Israeli society can also be traced to the racist assumptions of early Zionist settlers that Yemenite Jews and their Sephardic brethren were only fit to be “hewers of wood and drawers of water.”17 To this day, the lower economic and social standing of the Mizrahi is bolstered by the Israeli equivalent of what W. E. B. Du Bois called a “psychological wage” offered to impoverished European Americans on account of their whiteness: you may be poor, but at least you are not Palestinians.

Ultimately, it was the solution of producer collectives, operating on the principles of self-labor and mutual aid, that proved to be the only sustainable economic arrangements for exclusively Jewish agricultural employment. These took a variety of forms: the moshav ovdim, or small-holders cooperative; the fully collectivized settlements of the kibbutzim; and the “middle-class” moshavim, which did not prohibit the hiring of Arab day labor. Pooled resources, group purchasing and contracting, and communal cooking and living proved to be more cost-efficient than a household system based on individual wages. The savings were supposed to cover the additional expense of “culture,” considered indispensable for the literate Ashkenazi but no...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Halftitle Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Contents

- Acknowledgments

- Author’s Note

- Preface: Point of Entry

- Introduction

- 1. Conquest and Manpower

- 2. From Kurkar to Concrete and Back

- 3. Old and New Facts

- 4. Extract, Export, and Extort

- 5. Human Gold

- Notes

- Index