eBook - ePub

Realizing the Potential of Public–Private Partnerships to Advance Asia's Infrastructure Development

- 358 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Realizing the Potential of Public–Private Partnerships to Advance Asia's Infrastructure Development

About this book

This publication highlights how public–private partnerships (PPPs) can be effective to meet Asia's growing infrastructure needs. It shows how governments and their development partners can use PPPs to promote more inclusive and sustainable growth. The study finds that successful PPP projects are predicated on well-designed contracts, a stable economy, good governance and sound regulations, and a high level of institutional capacity to handle PPPs. It is the result of a collaboration between the Asian Development Bank, the Korea Development Institute, and other experts that supported the theme chapter "Sustaining Development through Public–Private Partnership" of the Asian Development Outlook 2017 Update.

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

At the moment all of our mobile-responsive ePub books are available to download via the app. Most of our PDFs are also available to download and we're working on making the final remaining ones downloadable now. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access Realizing the Potential of Public–Private Partnerships to Advance Asia's Infrastructure Development by Akash Deep, Jungwook Kim, Minsoo Lee in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Business & Government & Business. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

CHAPTER 1

Overview

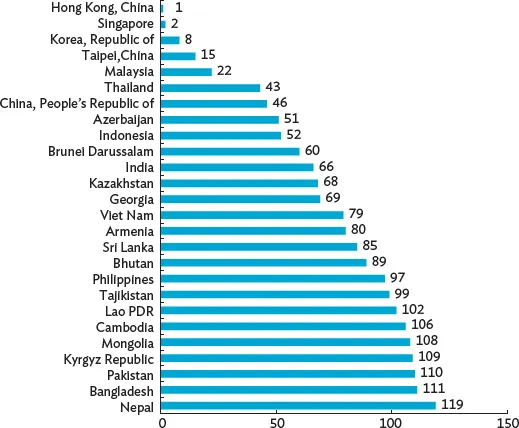

Developing Asia’s remarkable economic performance since the 1980s comes in no small measure from its great strides in building infrastructure. Even so, the region still faces significant difficulties in delivering infrastructure services caused by the huge gap in infrastructure investment that translates into many unmet needs. Access to physical infrastructure and associated services remains inadequate, particularly in poorer areas. Over 400 million Asians live without electricity, 300 million without safe drinking water, and 1.5 billion without basic sanitation. And even those using these services often find the quality is inferior in both rural and urban areas. Notable problems are intermittent electricity, congested roads and ports, substandard water supply and sewerage, and poor-quality school and health facilities. The World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 shows that many economies in developing Asia are in the bottom half of the ranking on infrastructure (WEF 2017) (Figure 1.1).

Figure 1.1: Infrastructure Ranking of Developing Asian Economies, 2017–2018

Lao PDR = Lao People’s Democratic Republic.

Source: World Economic Forum. 2017. Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018. Geneva.

The infrastructure gap is the result of both a lack of financial resources and innovative and efficient channels to mobilize resources for desired development outcomes. While the need to build up infrastructure is widely recognized in the region, tight fiscal conditions and limited public sector capacity prevent most countries in developing Asia from making significant headway in narrowing their infrastructure gaps. A long sought-after solution has been to get the private sector to help fill the infrastructure gap. The private sector clearly has a lot to offer in many areas of infrastructure delivery, including improving operational efficiency, granting incentivized finance, promoting project innovation, and technical and managerial skills. An effective way for the private sector to maximize its comparative advantages is to redraw its relationship with the public sector to share roles and responsibilities in providing public goods and services more efficiently. To this end, the Public–Private Partnership (PPP) approach could transform how both sectors collaborate to deliver infrastructure services. The World Bank defines PPPs as “a long-term contract between a private party and a government entity, for providing a public asset or service, in which the private party bears significant risk and management responsibility, and remuneration is linked to performance” (World Bank 2017a). The Asian Development Bank (ADB) and the Inter-American Development Bank define PPPs similarly.

This book evaluates the major challenges that Asia must overcome to get more PPPs off the ground and to use these partnerships far more effectively than is currently the case. It examines optimal ways of sharing risk in these partnerships, proposes financial instruments that can promote private financing for PPPs, and suggests roles that multilateral development banks (MDBs) can play in mobilizing finance for PPPs. All these measures are powerful catalysts for bridging the risk gap that is holding back Asia’s infrastructure development. The book presents country evidence and experiences from across the region to draw lessons and suggest ways for PPPs to unlock their potential for helping secure sustainable development. The Republic of Korea’s considerable experience in implementing these partnerships holds many useful lessons—successes and shortcomings alike—for countries in developing Asia trying to increase private participation in infrastructure.

Using PPPs for Building Infrastructure

The fundamental idea behind a PPP is not new. Private firms have been involved in delivering public services for decades in a variety of configurations. Since the 1980s, however, different PPP modalities have acquired distinct characteristics as experience has been gained in delivering a broader range of public goods and services, and partnering across multiple project stages, such as building, financing, and operation and maintenance. PPPs are being increasingly used in Asia, but the level is still quite low compared with developed countries. While the risk-sharing characteristic of PPPs makes this modality more attractive than traditional procurement, the complexity of PPPs is an obstacle to these partnerships.

The Impetus for Participating in a PPP

Building and upgrading infrastructure is widely acknowledged to bolster and sustain economic activity. Infrastructure helps emerging economies avoid unnecessary bottlenecks. And economies at all levels of development need infrastructure to improve connectivity, and to be able to advance agendas for economic development. The increased use of PPPs as a procurement method by countries and across sectors is being driven by expectations that these partnerships will deliver better-quality and more affordable infrastructure services.

PPPs can be particularly effective in reducing poverty by using them to develop social infrastructure that provides welfare services, such as basic health care, clean water, primary and secondary education, and housing. But, so far, this has not been done on a large scale in Asia. Data from IJGlobal show that, from 2000 to 2016, Asia accounted for only 5% of all PPP projects in education, health care, housing, and other social sectors, compared with 90% in Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries.

The benefits of infrastructure PPPs are the functional features of these partnerships; that is, a life-cycle perspective on the provision and pricing of infrastructure, a focus on service delivery, and sharing risks between the public and private sectors. Well-structured PPPs manage risks by allocating them across both sectors in a way that optimizes their cost and aligns incentives for performance. In PPPs, design, construction, and operational risks are typically passed on to the private partner. The private partner calibrates the design of, say, a road or new airport that responds to life-cycle costs and to meet performance obligations set out in the contract. Private partners innovate when risk-sharing provides incentives to avoid failure, and deliver timely and cost-effective physical infrastructure and infrastructure services.

Successfully carrying out PPP projects requires good governance and, if needs be, governments redesigning their regulatory and policy institutions. The institutional improvements required to implement PPP projects can also help establish a more robust investment environment for other private sector activities.

Asia’s Changing PPP Landscape

PPPs in developing Asia have evolved considerably in recent years. Governments are no longer the sole provider of essential public assets and services. And, although investments in infrastructure are still dominated by the public sector, the private sector is playing a larger and increasingly important role in developing, building, and improving public goods and services.

The World Bank’s Private Participation in Infrastructure Database—a widely used resource in this book—has logged over 6,400 infrastructure PPP projects that have at least 20% private ownership and reached financial closure in 139 low- and middle-income countries. The database is a valuable resource for gauging PPP trends, particularly in energy, telecommunication, transport, and water and sewerage. The database shows that the number of PPP projects that reached financial closure in developing Asia between 1991 and 2015 rose by a compounded annual growth rate of 11% (ADB 2017a).1 In aggregate, the number of PPPs in developing Asia account for half of all PPPs in developing countries. But the distribution of PPPs is uneven across countries and sectors. More than 70% are in East Asia and South Asia, and 90% of that share is in India and the People’s Republic of China. Even so, PPPs are gaining ground in Southeast Asia, particularly in the larger economies of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam. Central Asia and the Pacific together account for only 2% of the region’s PPPs.

The Economist Intelligence Unit’s 2014 Infrascope analyzed the readiness of countries in Asia and the Pacific to deliver sustainable PPPs (EIU 2015). It reported significant improvements in developing Asia in how governments handle PPP projects, based on its evaluation of regulatory and institutional frameworks, the investment climate, and the availability of finance. Of the 19 countries surveyed, India, Japan, the Philippines, and the Republic of Korea were considered to have “developed” PPP markets: 10 countries were classified as having “emerging” PPP markets in terms of their capacity to select, design, deliver, manage, and finance domestically PPP projects. The PPP market in the People’s Republic of China was the most mature of the economies in the emerging group. Infrascope classified three countries—Georgia, the Kyrgyz Republic, and Tajikistan—as having “nascent” PPP markets, where the institutional and technical capacity required to deliver complex PPP projects was not in place.

Obstacles to Attracting Private Investments in Infrastructure

PPP investment in five major Southeast Asia economies—Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Thailand, and Viet Nam—has been less than 1% of their annual gross domestic product (GDP) since the first decade of the 2000s. Project cancellations remain a big disincentive, not least because of high sunk costs. From 1991 to 2015, PPP projects with $41.6 billion in initial committed investment were canceled, affecting 6.3% of all committed PPP investment in developing Asia.

The World Bank (2017b) assessed the performance of 82 economies in four thematic areas of PPP processes: preparation, procurement, contract management, and unsolicited proposals. Although the World Bank found that Asia and the Pacific was close to the global average score in its rankings for these areas, its report showed that only 13% of countries in the region have detailed procedures to ensure the alignment of PPPs with public investment priorities.

Weak governance in many developing Asian countries can make PPPs less attractive, and may discourage private sector investment in infrastructure PPPs. Countries in developing Asia get low rankings in the World Economic Forum’s Global Competitiveness Report 2017–2018 on the quality of their legal and institutional environment. Hindering the whole PPP process are legal gaps that affect these partnerships, PPP policies lacking cohesion, redundant contract processes, and laws and regulations that change unpredictably. According to businesses in the region, the most pressing problems affecting investor confidence are lapses in law and order, government inefficiency, corruption, and political instability. Many governments do not have the institutions and capacity to handle PPP projects, and only half of developing Asian countries have dedicated PPP units. These have numerous and varied roles, including coordination, quality control, and accountability to procurement processes, and they provide transparency in PPP negotiations.

The political vulnerability of PPP projects in the region is also a longstanding concern for infrastructure investors, with these projects less likely to be implemented in countries where sovereign risks are high. In developing Asia, 59% of countries are unrated and, therefore, considered risky by international lenders. Twenty-six percent are rated below investment grade, and only 15% lie at or above investment grade.

Mobilizing More Financing for Infrastructure

For developing Asia to maintain its growth momentum and eradicate poverty, the region needs to spend an estimated $22.6 trillion—$1.5 trillion annually (in 2015 prices) from 2016 to 2030—in transport, power, telecommunication, and urban water and sanitation. Factoring in climate mitigation and adaptation costs raises the investment requirement to $26.2 trillion—$1.7 trillion annually—or 5.9% of developing Asia’s projected GDP in 2030 (ADB 2017b). The region invested $881 billion in infrastructure in 2015 (for 25 ADB developing member countries with sufficient data, comprising 96% of the region’s population). This is well below the estimated $1.2 trillion (baseline) or $1.3 trillion (climate adjusted) annual investment needed during 2016–2020 for these countries to maintain their growth momentum and eradicate poverty.

Just over 90% of funding for infrastructure development in the region comes from public spending. ADB estimates that raising more public funds through improving tax administration or reorienting other budget expenditures could raise additional resources for infrastructure equivalent to 2% of GDP for 24 of its 25 developing member countries (that is, excluding the People’s Republic of China). This would bridge 40% of the estimated investment gap during 2016–2020. For the private sector to fill the remaining 60%, it would have to increase investments to $250 billion a year over this period from an estimated $63 billion in 2015. Attracting investments at this level will require highly bankable projects that are perceived to present low or moderate risk to investors.

Indeed, mitigating the sizable risks associated with infrastructure investments in the region could go a long way toward attracting private capital to help fill the infrastructure gap. A PPP project allocates risks to the partners that can best manage them, thereby enabling the public sector partner to mobilize financing from private sources for public infrastructure. Mobilizing these financial resources, however, will require a coordinated effort by governments and private investors, which is the main challenge that policymakers face in attracting private capital to long-term infrastructure projects.

Project Finance and Optimal Risk-Sharing

The rise of project finance for long-term infrastructure PPP projects proves that financing structures are important to project success. Project finance involves creating a distinct legal and economic entity to act as the counterparty to various contracts involved in a PPP and to get the financial resources required to develop and manage a project. Setting up a special purpose vehicle is the necessary first step for the private sector to deliver infrastructure through a PPP.

Project finance is vital for improving investment management and governance, but it needs to be structured in a way that allocates risk to the parties that are best able to manage them. A solid corporate governance structure for project finance can improve the management of risk in infrastructure projects. Because of the many risks present in large PPP transactions, project finance is structured to match risks and their corresponding returns to the parties best able to manage them. Facilitating the equitable and rational distribution of risk creates an environment in which investors can work together easily. Project finance also allows the leveraging of long-term debt, which is necessary to finance high-capital expenses. The use of project finance as a financing tool may also help mitigate information asymmetry problems that are typically present in large infrastructure PPP projects.

Sources of Project Finance

In all financing structures, equity financiers own the asset, exercise control over decisions on the asset, and receive any profits that it generates. The proportion of debt to equity is ultimately determined by a project’s contractual and capital structures, and how various risks are mitigated.

Debt finance constitutes the largest component of financing for PPP projects. Among debt providers, commercial banks are the largest source of debt finance for infrastructure projects, both in Asia and globally, because of several clear advantages that they have. Banks play an important monitoring role in lending, and bank lending has the flexibility to meet the particular need of infrastructure projects for funds to be gradually disbursed over the long term. Banks can provide debt restructuring when needed, and do so earlier and with greater pricing certainty through the structured tender process of a well-designed PPP. But their ability to provide debt financing for developing Asia’s infrastructure needs is limited, partly because bank capital requirements under Basel III have tightened requirements for project finance lending by banks. The underdeveloped capital markets of Asia’s emerging economies are also making it harder for PPP projects to tap debt finance (BIS 2016).

Project bonds are another source of debt financing for PPP projects. Bond financing is normally more attractive than bank financing because bond investors can lend at fixed rates and for longer maturities. Bond financing can also be drawn from investors with natural long-term liabilities, compared with the relatively short-term funding sources of banks. Clearly, bonds have several advantages over bank lending for providing the sort of financing that is well suited to long-term PPP contracts, but they are not widely used in developing Asia. The rarity of project bonds reflects an aversion in corporate bond markets to diversity in credit quality, and, as earlier noted, the credit ratings of developing countries in Asia are at the lower end of investment grade or below. Credit enhancement therefore has a vital role to play if project bond financing is to become more widely used in...

Table of contents

- Front Cover

- Title Page

- Copyight Page

- Contents

- Tables, Figures, and Boxes

- Foreword

- Acknowledgments

- Abbreviations

- 1 Overview

- Part I The Benefits and Risks of Public–Private Partnerships

- Part II Mobilizing Finance for Public–Private Partnerships

- Part III Lessons from the Experience of Using Public–Private Partnerships in Developing Asia

- Contributors

- Index

- Back Cover