- 128 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Jethro Tull's Aqualung

About this book

Formed in 1968, Jethro Tull are one of rock's most enduring bands. Their 1971 album Aqualung, with its provocative lyrical content and continuous music shifts, is Tull's most successful and most misunderstood record. Here, music professor and fan Allan Moore tackles the album on a track-by-track basis, looking at Ian Anderson's lyrics and studying the complex structures and arrangements of these classic songs.

Tools to learn more effectively

Saving Books

Keyword Search

Annotating Text

Listen to it instead

Information

1.

Aqualung. It was buying your first great-coat that did it. It simply wasn’t possible to find something near to that tatty, chequered monstrosity from which a flute, of all things, issued so precariously, but a great-coat from the local army surplus was close enough, particularly if you were somewhere out in the provinces. That image of this crazy, probably dangerous individual with unkempt hair, strangely wandering eyes, and an inability to keep both feet on the floor at the same time that we saw on Top of the Pops as Jethro Tull and his anonymous backing musicians performed ‘Witch’s promise’ in the winter of 1970, remains to this day one of the most striking I can recall.10 And, when the great-coat appeared in all its glory clothing Jethro’s alter ego on the cover of Aqualung, it was clear to us that we were insiders, that we lived in exactly the same crazy world, that we ‘knew what it was all about’, even if we didn’t know what it was all about.

With the benefit of thirty years of listening, maybe it was principally about distaste, about the after-effects of the souring of the countercultural dream. But it was also about the control one exerts over one’s own destiny, or the lack of it. And it was therefore about the acknowledgment that changing society wasn’t quite as easy as the hippies had pretended. That difficulty, a posing of some of the necessary questions, was very much what Aqualung was all about, even if it didn’t provide any real answers. (And, if it had, what use would it have been? Who ever managed to bring about anything worthwhile by adopting someone else’s manifesto?)

Aqualung appeared in the early part of 1971. As Ian Anderson himself would put it later, ‘[a] comfortable and convenient step or two behind the cutting edge of “progressive rock” ‘.11 This sharp end was represented by In the Court of the Crimson King, its gothic splendour and message of doom so heavy that it seemed to belong more to an underworld than to the grey skies of the England into which Aqualung wandered. And Aqualung belonged in 1971, too. Society was not at ease with itself. A first spate of plane hijackings had sent waves of fear through affluent Western society; Jimi Hendrix and Janis Joplin had both stupidly died within the past six months; the first British troops in Ulster were killed as their role became politically highly sensitive; UK unemployment was skyrocketing; Enoch Powell was stoking the fires of racism in speaking out against immigration; Cuba was threatening to erupt again as a battleground between the USA and the USSR; and ‘Women’s libbers’ marched on London. And, as if that wasn’t enough, pop music was busy galloping off down the course on which it had been set in 1966 by John Lennon’s ‘Tomorrow Never Knows’, certainly the boldest attempt within this most ephemeral of activities to make music for the sake of doing so, leaving to others any concern with whether such efforts would come to seem meaningful. And meaningful they did prove to be, in their foundation of a psychedelic otherness that became common mining ground over the next few years. Aqualung, though, in the light of Ian Anderson’s anachronistic inveighing against the taking of mind-altering substances,12 suggested that ‘otherness’, being different, beyond society’s co-option, was part and parcel of everyday existence, an otherness that was not the pretty thing of the hippies, but was weird, unkempt, and strange.

Aqualung arrived at the right time, then. By 1971, rock was established as a genre to be reckoned with. Post-war hardship was well and truly past, the hysterical brightness and hedonism of Swinging London consigned there also. Rock13 was enthroned as the medium of rebellion, the embodiment of the newly-coined ‘generation gap’14—it was a music that our parents couldn’t understand. Although this intentional generational separation through music can be found in the teddy boys’ use of rock’n’roll in the late 1950s, and in the mods & rockers battles on the seafronts of the 1960s, these were mere skirmishes. From the late 1950s onwards, the roots of the music of rebellion were being laid far more surreptitiously, in the blues clubs run by Cyril Davies and Alexis Korner, and that finally blossomed in the work of John Mayall, Graham Bond, Davy Graham, Peter Green, Eric Clapton, and others in the mid 1960s. It was the British blues boom, and the appropriation of the music of an underclass that established rock as more-than-ephemeral rebellion, and enthroned the electric guitar as the axe with which to cut down the dead music of the past. And, in Aqualung, Cross-Eyed Mary, and the rest of their cast, Jethro Tull set up precursors to the grotesque and marginalized who would become the staple of metal and punk, and so remain to this day. However, these misfits are in part presented to us with what borders on compassion, another legacy of the counterculture: a dominant image here is that of Shirley MacLaine, sad character that she is, at the end of Sweet Charity, presented with a flower to mark the resurrection of hope—it is not too difficult to imagine Mary in that role. And so Aqualung sits at the crossroads between these two positions—it represents a society rebelling against … whatever there is to rebel against, and yet not with the unfocused mindlessness of youth, but with the compassion that potentially recognises each of us in those who do not have the wherewithal to rebel.

It would be tempting to suggest that these two sides were simply and unambiguously presented on the album. After all, in its original vinyl guise, it was clearly presented as two distinct sides—not only was it physically necessary to turn the thing over half way through (this was not one of those albums where side two was often unheard, at least due to the cunning placing of ‘Locomotive Breath’ towards the end), but each side appeared to be given its own title, that of the cut that began them, namely ‘Aqualung’ and ‘My God’. Some listeners have even constructed narratives in order to make sense of each of these sides. And it is true, side two does focus on Ian Anderson’s troubled relationship with established religion, while side one can be seen as consisting of songs observing various aspects of urban experience, but this is to create a division between two clear identities that is not necessarily there. In Anderson’s own view:’… it was merely that there were some common threads running through some of the songs … [t]here are certainly songs that have absolutely nothing to do with any other songs’ (not a view I entirely agree with, as will become clear) ‘… the songs were structured into those two sides after it was all done’.15 Even at the time, he was insistent that there was no ‘concept’ involved, no narrative thread: ‘[I]t doesn’t tell a story, doesn’t have any profound link between tracks’.16 Indeed, it was only journalists’ propensity to finding such links that determined Anderson to give them what they were asking for: Thick as a Brick.17 That listeners do create that identity, do take it as a concept album, irrespective of the original intentions, is important, as we have noted (their freedom to do so also has Anderson’s imprimatur, of course, and so Anderson perhaps needs to take full blame for the decision). More important here, though, is the presentation. There is a difference between the original vinyl and the subsequent CD packaging. On the CD initially released in 1983, the painting of Aqualung in Steptoe rig (seemingly hiding something under his coat) is backed with the track listing, while the more compassionate painting of Aqualung sitting in the gutter appears on the inside—originally, these two paintings appeared on front and back of the gatefold sleeve, with the track listing on the inside, together with the painting of the band rehearsing in an abandoned church (which was missing entirely from the 1983 CD, but is restored on the 1998 release). The compassionate pose has been down-graded, then, for contemporary audiences, while the gothic lettering that would subsequently play such a part in early ‘death metal’ (and hence be associated with dangerous grotes-queries and occult fantasies) is highlighted. (In 1987, Tull would unbelievably win the heavy metal Grammy for Crest of a Knave, while 1982’s Broadsword and the Beast was read on the Continent, at least, as tapping into the gothic end of metal.) Even in the spring of 1971 this sleeve appeared portentous, perhaps suggesting that the wake-up call the album issued had deeper targets. And it was easy to confuse this mythical creature, Aqualung, with the one (Ian Anderson) we saw. So much of Jethro Tull’s career has been an exercise in identity construction, as stylistically they swerve from early blues, R&B, and hard rock straight through progressive rock (Passion Play), folk rock (Songs from the Wood), and new wave/synthesizer rock (A), on to so-called heavy metal (Crest of a Knave), back to quasi-blues (Catfish Rising) and on to world music (Roots to Branches). Ian Anderson, who was already becoming ‘Jethro Tull’, himself became Aqualung—the straggly hair and coat that identify Aqualung are each well in evidence clothing Anderson on the sleeves of both the earlier albums This Was and Benefit.

2.

Extricating a new album from its sleeve, taking care not to put your sweaty mitts on the vinyl itself, was always something of a ritual—the anticipation to savour it, but the fear of dropping the stupid thing (I never did get to hear Roxy’s Stranded at the time, for precisely that reason). With the best albums, those first few seconds after the needle had touched down launched you somewhere new, and ‘Aqualung’ was no exception. That opening guitar riff, that short little phrase (for that is all a riff is) was fierce. It just hit you deep in the stomach. A simple little thing, dropping suddenly in pitch and then gradually climbing back up to its first note, but not quite getting there (and dwelling on that failure). And the tone, that fizzy guitar sound of Martin Barre’s—full of enormous sonic potential, but keeping it reined in just for the moment, and only for the moment, as later songs show.

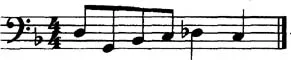

I’ve done the unforgivable—I’ve jotted down that opening riff (see fig. 1), fixing it, draining it of its power so that it can be calmly pondered on the page. Have you ever contemplated the wonder of the butterfly? Before movie photography, butterflies were studied by killing them and pegging them out. In a sense, that’s what I’ve done with this riff—laying it flat on the page so that its details (such as they are) can be studied ‘out of time’. It’s not quite as devastating as killing a poor Emperor, of course, since the music can always be set to go again. Indeed, I would argue that paying very close attention to any of this music is only ever worthwhile if the music is ‘put back together’ again afterwards. However, on with the demonstration.

Even in jotting down that riff, you can see the alteration I have had to make to that first note (the ‘D’) as it returns (as it becomes a ‘D flat’, a flattened version of the original note). It becomes a foreign note, a transgression, a note that does not belong. More than that, it becomes the note on which the music alights as the whole band enters after Anderson’s initial phrase. No gentle entry this, the dangerous alteration is present right at the outset. Why dangerous? The opening riff is in G minor—the switch 11” in (‘eyeing little girls’)18 is to D flat major—further away, in musical terms, you cannot get. Imagine for a moment that the history of painting consists of canvases that gradually shade from one colour into the next—purples shade into blues into turquoises on one, oranges into reds into pinks on another, but the colours are kept well marshalled. Then a painting bursts open in which blues sit next to oranges, greens next to reds. That is the force of the opening to ‘Aqualung’. (The analogy is inexact, of course, for green and red sit well next to each other for physiological reasons—the same is not the case in music—in music, opposites repel.) So, right at the outset, irreconcilable opposites are presented within the very notes of the melody. As I have suggested, these opposites are fundamental to the song, to the album, and to the Jethro Tull worldview.

‘Aqualung’ plays against the expectations of rock right from the outset. The riff is set apart from the song, through being separated in time. We hear it—we catch our breath—we hear it again—we wait in anticipation as Clive Bunker’s drums thunder out a triplet rhythm that has connoted menace ever since it started being used to signal the approach of the Apaches in run-of-the-mill Westerns.19 We hear it a third time, finally knit into the song under Ian Anderson’s opening line. Each of these—the riff, the silence—lasts the same length of time, four beats, i.e. one bar. So far, then, we’ve had five bars. Then that switch to the new key and the slightly more comforting strummed guitar (but with a menacing, smashed crash cymbal on the off-beat) sitting behind the riff as we hear the rest of the stanza. Note how the tom-toms appear at either extreme of the stereo space (audible from as early as 11” in), making clear right from the outset how ‘extensive’ that space is, how much ‘room’ the band actually has within which to manoeuvre (purely coincidentally, the album was recorded in what had been a church, rather than the small cosy studio commonly used at the time). I shall insist on reading this metaphorically, as representing the intellectual space the album will attempt to cover (and I hope by the end this will not sound so precious as it does at the moment). How long do we get as a result of this switch, before things come to rest? Six bars, actually (but of entirely different music). Now we are beginning to be on familiar ground, because one further hearing of the riff (at 23”) is followed again by the six-bar passage. And that same again, and again, now with a richer riff, slightly less bare, doubled in thirds (again, this creates a sense of ‘size’, because there is only one guitar player, but two guitars being played: over-dubbing is, by 1971, becoming a common device for ‘magnifying’ the size, and hence potency, of the music, with the inevitable risk of bombast that makes possible). We are a minute into the song, and its course seems pretty clear. Here is this thoroughly disreputable being, described objectively (‘spitting out pieces of his broken luck’—for years I heard it as ‘lung’, which just made it even more disgusting), with distaste (just listen to the way the word ‘nose’ is squeezed out from the side of Anderson’s mouth—almost enacting the dripping of Aqualung’s snot). He’s even addressed at one point, as if in derision—‘hey, Aqualung!’ but with no response forthcoming, of course.

Then, at 1’04”, the whole scene changes. Well, that in itself is not unusual—songs often divide up into verses and choruses, after all, and they almost invariably did so in the 1960s. But is that—verse and chorus—what we have here? If so, which is which? Verses tend to push the narrative of a song forward while a chorus, in its repetitiveness, provides space to reflect. And, at first, it seems that this is what’s happening here in a strange sort of fashion (except that choruses are also often associated with snappy hooks and that certainly isn’t the case here). We get a complete change of texture—no riff, acoustic guitar gently strummed in the foreground, and the voice sounding as if at some distance. And, after the irregularity of the opening, the regular four-beat groove that takes over here sounds almost nostalgic, almost wistful. (In pop music, everything tends to proceed in fours—four beats to the bar, four bars to the phrase—well, more correctly, the ‘hypermetrical ...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Introduction

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

- Copyright

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn how to download books offline

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 990+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn about our mission

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more about Read Aloud

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS and Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app

Yes, you can access Jethro Tull's Aqualung by Allan Moore in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Social Sciences & Popular Culture. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.