- 464 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

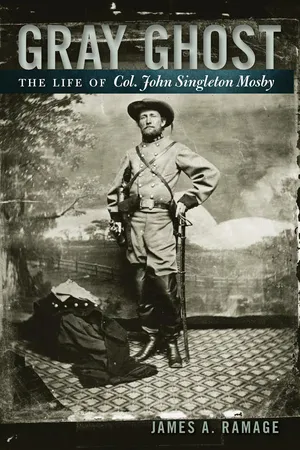

Yes, you can access Gray Ghost by James A. Ramage in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in History & American Civil War History. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Publisher

The University Press of KentuckyYear

2010Print ISBN

9780813192536, 9780813121352eBook ISBN

97808131384971

Mosby's Weapon

of Fear

Union cavalry charging with whirling sabers against Mosby's men suddenly realized that nothing in their drills or training had prepared them for this, for Mosby threw away the rules and never fought fairly. Here was no gentlemanly thrust and parry, but revolver bullets, noise, and smoke; men falling to the ground wounded and dead; and riderless horses jumping around out of control. The Union commander was usually one of the first down, and in shock and confusion his men had the urge to drop their reins and allow their horses to behave naturally and run away. “We considered that to meet Mosby and his men at close range meant certain death,” and “often wondered what kind of a man he was that he could give us such warm receptions,” recalled an 8th Illinois Cavalry veteran.1

John Singleton Mosby had no military schooling but was a lawyer and student of history and literature, quoting lines from the poetry of his favorite author, Lord Byron. He was a small, thin man—5 feet, 8 inches tall and 128 pounds—and an outstanding horseman who could handle a horse as smoothly as a steeplechase champion. Mounted on a magnificent gray horse, one of the fastest in the column, he led the assault, bridle reins in one hand, Colt revolver in the other. His eyes flashed, and he yelled in a high-pitched, powerful voice. In the heat of battle a transformation came over his face: deep and powerful emotions welled up, and his thin lips opened on his perfect white teeth as a satirical smile illuminated his countenance. He was no hedonist—his only luxury was freshly ground coffee—but these Civil War melees were the highest pleasure in his life.

The mounted charges and countercharges of Mosby's 43rd Battalion Virginia Partisan Rangers seemed spontaneous and unorganized, but every detail of his warfare and tactics was the result of extremely careful planning and execution by one of the most brilliant minds in the history of guerrilla war. Mosby was one of the most self-disciplined, focused, and indefatigable individuals who ever lived, and his goal was to win the crowning laurel of guerrilla war by penetrating the minds of the enemy and using fear as a psychological force multiplier. He created the illusion of ubiquity, the fear that he might appear anywhere at any time, and used this edge to operate for more than two years and three months behind enemy lines within a day's ride of Washington and still had the tactical initiative when the war ended.

Mosby specialized in overnight raids with men and horses rested and well nourished from a few days of freedom between operations. For him a perfect mission included entering the target area undetected, rapidly executing the mission, and withdrawing quickly, with no alarms raised and no fighting. He accomplished all of these goals in his most famous raid. Guided by a Union cavalry deserter, he infiltrated Union lines in Fairfax County with twenty-nine men on the night of March 8, 1863, captured Union general Edwin H. Stoughton and thirty-two men, and withdrew undetected with no shots fired. Confederate cavalry commander Gen. James Ewell Brown “Jeb” Stuart declared the operation a “brilliant exploit” and issued a special order proclaiming: “The feat, unparalleled in the war, was performed, in the midst of the enemy's troops at Fairfax Court-House, without loss or injury.”2

Practicing the goal of never fighting fairly, Mosby ambushed the 6th Michigan Cavalry twice on the same overnight raid, and their commander, Col. George Gray, said: “Mosby did not fight fairly. He surprised me, and the night before had bushwhacked some of my men.” Mosby understood that success depended on accurate reconnaissance and therefore had some of the best scouts in the Confederacy, local men familiar with every road and by-path and acquainted with the people living in the target area. He often scouted himself as well, both a few days before a raid and again immediately before deciding whether or not to attack. Only he knew his plans; he told no one, and the men had no idea whatsoever where they were going until they arrived. Once the march was underway he would tell the guide, and him alone.3

Adopting the fastest transportation available, Mosby's men had the best Thoroughbreds the Yankees could provide. Each Ranger had several and rotated them to have a fresh mount for each raid. Most were jumpers, accustomed to leaping high fences and dashing across fields for rapidly getting away. Union troops who watched them scatter into the woods said their horses jumped like deer, and Gen. Wesley Merritt reported: “The guerrillas, being few in numbers, mounted on fleet horses and thoroughly conversant with the country, had every advantage of my men.”4

Normally, cavalry on the march sent up a humming sound that could be heard for hundreds of yards at night. Sabers and scabbards clanked, canteens jingled, and hooves clattered. Mosby, carefully practicing stealth, forbade sabers, canteens, and clanking equipment; his column moved so quietly that civilians lying in their beds in houses next to the road recognized when Mosby's men were passing in the night—the only sound was the pounding of hoofbeats. Near the target he would veer off into soft fields or woods, and it was so quiet that the men could hear whippoorwills calling in the distance. “Silence! Pass it back,” he ordered, and from that point he directed only with hand signals. If attacking dismounted he would have the men remove their spurs and leave them with the horses and horse-holders. He walked in soft snow or used the sound of the rain and wind to cover footsteps, and once timed his final pounce with the sound of coughing by a Union horse. “We made no noise,” he wrote, and one of his men recalled, “Our men were in among the prostrate forms of the Yankees before they were fairly awake, and they assisted some of them to unwind from their blankets.”5

Modern military studies of sleep deprivation indicate that cognitive skills deteriorate after one night without sleep; after two or three nights, performance is considerably impaired. Confederate general John Hunt Morgan's men were falling asleep in the road on his Indiana-Ohio Raid, and his exhausted scouts failed him at Buffington Island by reporting that the ford was guarded by regular forces when they were only a few frightened home guards. Abel D. Streight became groggy from exhaustion and sleep deprivation on a raid in Alabama in the spring of 1863, and Nathan Bedford Forrest deceived him into surrendering to a force less than half his size. H. Judson Kilpatrick became worn down and lost his nerve in his raid on Richmond, Virginia, with Ulric Dahlgren early in 1864 and was driven away by defenders that he outnumbered six to one. But Mosby carefully saved the energy of his men and horses, moving slowly into a raid for maximum performance in the fight and hasty withdrawal. He preferred to strike at about 4:00 A.M. when guards were least alert and reserves most sound asleep. He said that it was easy to surround sleeping men and that it took five minutes for a man to awaken and fully react out of a deep sleep.6

Mosby and his men wore Confederate uniforms on missions so that they could claim their rights as prisoners of war if captured. But using disguise and perfidy was just as illegal as being out of uniform—under international law the penalty was to be shot or hanged. Ignoring this provision, Mosby and his men frequently masqueraded as the enemy. During cold weather they wore Union overcoats, and when they had Union prisoners they would place them in front to create the appearance of Union cavalry. They usually marched in leisurely go-as-you-wish style like friends out for a ride, but for disguise they would form in column of fours and appear to be well-drilled blueclads. When it rained they wore rubber ponchos convenient for approaching the enemy with revolvers drawn, concealed under the rain garments.

Mosby achieved the objective of using fear as a force multiplier, diverting several times his own number from the Union army and creating disruptions and false alarms. “A most exaggerated estimate of the number of my force was made,” he wrote. He seemed to possess a sixth sense, enabling him to sense enemy weaknesses. Like an entrepreneur forecasting the business cycle, he had a tremendous instinct to select targets at the opportune time and place for maximum impact. Part of it was vigilance and alert scouting, but Mosby's record of locating and attacking weaknesses in enemy defenses was almost uncanny. A Union cavalry officer in the Army of the Potomac recognized it when he wrote: “Even now, from the tops of the neighboring mountains, his hungry followers are looking down upon our weak points.”7

Time and again Mosby danced on the nerves of opponents where they were most vulnerable. Philip Sheridan had great personal pride in his ability as a supply officer, and one of the last things he wanted was to have some of his wagons captured by guerrillas. Henry W. Halleck feared that Mosby would make headlines on his watch defending Washington and stain his reputation. Elizabeth Custer worried that Mosby might capture her beloved new husband, George. Mosby's psychological war even went to the extent of sending a lock of his hair to Abraham Lincoln; even though it was only a joke, it reminded Lincoln that outside the Washington defense perimeter Mosby reigned.

Mosby realized that making his name feared would give his warfare greater emotional impact. He insisted that his men make it clear when they attacked that they were “Mosby's men.” Rangers learned that the word “Mosby” was so powerful that it was useful in subduing a guard and preventing him from yelling or shooting. “I am Mosby,” a Ranger would whisper, and sometimes the captive would go into a daze, bowing his head and trembling in fear. When ordered to walk, one prisoner staggered as if drunk, another became nauseated and vomited, and another fell on his knees and raised his hands, pleading for life. When a Union soldier disappeared, his friends would say, “Mosby has gobbled him up,” or “He has gone to Andersonville.”8

Union opponents said Mosby's men seemed to be “almost intangible” demons and devils, and myth claimed that when they scattered into the mountains the tracks of their horses suddenly disappeared. “Nobody ever saw one;” a Union officer wrote, “they leave no tracks, and they come down upon you when you least expect them.” Northern journalists characterized them as “rebel devils,” horse thieves, “skulking guerillas,” “these nuisances that go on legs,” gang of murderers and highway robbers, accursed poltroons, cutthroats, “picket shooting assassins and marauding highwaymen,” “worse than assassins,” and “lawless banditti.” Union horsemen named their area “a nest of guerrillas,” “Devil's Corner,” “The Trap,” and “Mosby's Confederacy.”9

By the close of the war he had made himself the single-most-hated Confederate in the North. Northern newspapers designated him “the devil,” Robin Hood, horse thief, bushwhacker, marauding highwayman, murderer, rebel assassin, notorious land pirate, and guerrilla chief. Jack Mosby, the Guerrilla, a dime novel published with a yellow paper cover in 1867, described him as a tall and powerful desperado with a black beard, a cruel, remorseless man who enjoyed cutting men apart with his tremendous saber and riddling them with bullets from a varied assortment of pistols on his belt. In the book, he had his sweetheart make love to Union officers to lure them into his hands and delighted in hanging them by their arms and kindling a fire under their feet to force them to talk. In the cheap woodcut on the cover he appeared in a room in the Astor House in New York City, pouring Greek fire on his bed. Mosby was so well hated that into the next generation Northern mothers quieted their children with, “Hush, child, Mosby will get you!”10

On the other side, Southerners admired Mosby as a great hero. His portrait appeared in the book The War and Its Heroes, published in Richmond in 1864. Southern journalists considered him a “daring and distinguished guerilla chief” who made the country seem literally alive with guerrillas. Southern people named babies for him and told the tale that one day in the Shenandoah Valley a Union officer knocked on the door of a plantation house. A woman slave answered the door, and he asked if anybody was home. “Nobody but Mosby,” she answered. “Is Mosby here?” he inquired excitedly. “Yes,” she answered, and he jumped on his horse and rode away. Shortly, he returned, surrounding the house with a company of cavalry. He came to the door and asked if Mosby was still there. “Yes,” the woman said, inviting him in. “Where is he?” he demanded, and she pointed to her infant son in a cradle and proudly announced: “There he is. I call him ‘Mosby,’ Sir, ‘Colonel Mosby,’ that's his name.”11

On slow news days during the weeks of lull between battles, newspaper editors satisfied the hunger for war news with blockade-runner and guerrilla stories. Minor dispatches on Mosby were clipped and reprinted, making national news on both sides. Many days the same newspaper had several different accounts of his exploits, and the New York Herald probably set the record on October 15, 1864, with nine Mosby articles, most reporting his Greenback Raid on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad the previous day. He encouraged publicity, attempting to counter the myth that his men were criminals. When he captured Northern war correspondents he provided them fine food and cigars and turned on his charm, giving them some of their most colorful copy.12

John Hunt Morgan became a romantic hero of the Southern people, the symbol of guerrilla war and primary model for the Confederate Partisan Ranger Act. Mosby was the most successful partisan commissioned under the law. Morgan was killed September 4, 1864, and three days later the Richmond Examiner proclaimed Mosby “our prince of guerillas.” Southern news reports on Morgan were heroic in tone; Mosby articles were businesslike and factual like market reports. Under the banner “Mosby at Work,” statistics ticked off how many wagons he had burned and how many Yankees he had killed, wounded, or captured. Recounting the story of his capture of an infantry company guarding Duffield's Depot on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad without firing a shot, the Richmond Dispatch related that, when the besieged Federals inquired what terms of surrender he offered, Mosby said: “Unconditionally, and that very quickly.”13

Morgan and Stuart won the hearts of young women and Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson the adoration of grandmothers; Mosby had female admirers, but they made him feel uncomfortable. When the Confederate capital extended Mosby a hero's welcome in late January 1865 and the Virginia legislature and Confederate House of Representatives honored him, young women from the gallery rushed to obtain his autograph, and he wrote his wife Pauline that it was more frightening than being in battle. “If there had been any decent way of doing so I wd. have backed clean out,” he declared. Many young men daydreamed of fighting by his side, and Southern civilians identified with his attitude of defiance and irrepressible perseverance. “The whole Yankee army harks to Jack Mosby,” wrote Confederate Bureau of War clerk Robert G.H. Kean in his diary.14

Probably the highest praise that Mosby received in the war appeared in the Richmond Whig on October 18, 1864. He had been in Richmond recently, convalescing from a wound, and a few days later had returned to duty and raided Salem, temporarily halting Union construction on the Manassas Gap Railroad, and he had struck the B&O Railroad with the Greenback Raid.

The indomitable and irrepressible Mosby is again in the saddle carrying destruction and consternation in his path. One day in Richmond wounded and eliciting the sympathy of every one capable of appreciating the daring deeds of the boldest and most successful partisan leader the war has produced—three days afterwards surprising and scattering a Yankee force at Salem as if they were frightened sheep fleeing before a hungry wolf—and then before the great mass of the people are made aware of the particulars of this dashing achievement, he has swooped around and cut the Baltimore and Ohio road—the...

Table of contents

- Cover Page

- Title Page

- Copyright Page

- Dedication Page

- Contents

- 1 - Mosby's Weapon of Fear

- 2 - The Weakling and the Bullies

- 3 - “Virginia is my mother.”

- 4 - Scouting behind Enemy Lines

- 5 - Capturing a Yankee General in Bed

- 6 - Miskel's Farm

- 7 - Featherbed Guerrillas

- 8 - Unguarded Sutler Wagons

- 9 - Masquerading as the Enemy

- 10 - Seddon's Partisans

- 11 - Mosby's Clones in the Valley

- 12 - The Night Belonged to Mosby

- 13 - Blue Hen's Chickens and Custer's Wolverines

- 14 - The Lottery

- 15 - Sheridan's Mosby Hunt

- 16 - Sheridan's Burning Raid

- 17 - Apache Ambuscades, Stockades, and Prisons

- 18 - “All that the proud can feel of pain”

- 19 - Grant's Partisan in Virginia

- 20 - Hayes's Reformer in Hong Kong

- 21 - Stuart and Gettysburg

- 22 - Roosevelt's Land Agent in the Sand Hills

- 23 - The Gray Ghost of Television and Film

- Conclusion

- Notes

- Bibliographic Essay

- Acknowledgments

- Index