- 264 pages

- English

- ePUB (mobile friendly)

- Available on iOS & Android

eBook - ePub

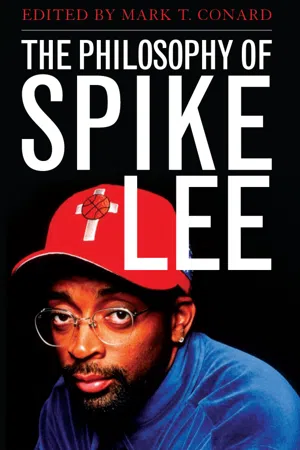

The Philosophy of Spike Lee

Frequently asked questions

Yes, you can cancel anytime from the Subscription tab in your account settings on the Perlego website. Your subscription will stay active until the end of your current billing period. Learn how to cancel your subscription.

No, books cannot be downloaded as external files, such as PDFs, for use outside of Perlego. However, you can download books within the Perlego app for offline reading on mobile or tablet. Learn more here.

Perlego offers two plans: Essential and Complete

- Essential is ideal for learners and professionals who enjoy exploring a wide range of subjects. Access the Essential Library with 800,000+ trusted titles and best-sellers across business, personal growth, and the humanities. Includes unlimited reading time and Standard Read Aloud voice.

- Complete: Perfect for advanced learners and researchers needing full, unrestricted access. Unlock 1.4M+ books across hundreds of subjects, including academic and specialized titles. The Complete Plan also includes advanced features like Premium Read Aloud and Research Assistant.

We are an online textbook subscription service, where you can get access to an entire online library for less than the price of a single book per month. With over 1 million books across 1000+ topics, we’ve got you covered! Learn more here.

Look out for the read-aloud symbol on your next book to see if you can listen to it. The read-aloud tool reads text aloud for you, highlighting the text as it is being read. You can pause it, speed it up and slow it down. Learn more here.

Yes! You can use the Perlego app on both iOS or Android devices to read anytime, anywhere — even offline. Perfect for commutes or when you’re on the go.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Please note we cannot support devices running on iOS 13 and Android 7 or earlier. Learn more about using the app.

Yes, you can access The Philosophy of Spike Lee by Mark T. Conard in PDF and/or ePUB format, as well as other popular books in Media & Performing Arts & Film & Video. We have over one million books available in our catalogue for you to explore.

Information

Part II

Race, Sexuality, and Community

(Still) Fighting the Power

Public Space and the Unspeakable Privacy of the Other in Do the Right Thing

Near the end of Spike Lee’s Do the Right Thing (1989), the two Italian American brothers Pino (John Tuturro) and Vito (Richard Edson) are arguing in the back room of their father’s pizzeria, where they work. Pino, the sullen, overtly racist older brother, is manhandling Vito, trying to impress on him the danger of getting too close to their multicultural—primarily African American—customers and, in particular, their delivery boy Mookie (Spike Lee). For Pino, the struggle is about maintaining a discrete and essential identity; earlier in the film he cautions his brother, “Remember who you are.” What he means is both “Italian American” and “American” as white—a whiteness that is set in essential opposition to blackness and is possible only through the constitution of blackness as something fundamentally Other. As the brothers wrestle, the overhead light swings above them in a disorienting blur of cartoonishly orange light and shadow; the handheld camera jostles and edges around them, ratcheting up the tension. Vito finally finds a purchase on his brother and insists, “You don’t know. You think you know, but you don’t know.” What does Vito mean by this?

Before suggesting an answer, I would like to reflect on the fact that even twenty years after its release, Do the Right Thing continues to spark discussion and controversy. Although Lee’s body of work is at times problematic, in particular with regard to its pervasive heteronormativity and its often troubling representation of women,1 Do the Right Thing remains a film to be reckoned with. The film continues to engender acute discomfort among audiences (especially, but not exclusively, white audiences), raising a number of questions about why its confrontation of what Lee calls the single most pressing problem in America—race and racism—is so threatening to generally held assumptions about race in America.2

The film, set on the hottest day of the summer in a multicultural neighborhood in Brooklyn, created a stir with its uncompromising portrayal of racial inequities. The heat aggravates the already brewing conflicts among the central characters: Sal (Danny Aiello), the Italian American pizzeria owner; his sons Pino and Vito; his slacker, deadbeat-dad delivery boy Mookie; the implacable Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), whose blaring boom box precedes him everywhere; and Buggin’ Out (Giancarlo Esposito), a wannabe militant who decides to boycott Sal’s for excluding African American celebrities from his all–Italian American “Wall of Fame.” These conflicts—some petty and others more serious—escalate over the course of the day into a bitter confrontation between Sal and Radio Raheem, resulting in a riot, the murder of Radio Raheem at the hands of the police, and the destruction of Sal’s Famous Pizzeria.

Vito’s contention about the status of his brother’s knowledge raises the question of claiming knowledge as the basis for dealing with others. Do the Right Thing mines this question and its consequences for how race-based injustices are framed and represented in American culture. In investigating how the film addresses race as an epistemological problem—that is, as a problem rooted in knowledge (or a lack of knowledge)—I begin with a brief synopsis of philosophical skepticism and suggest what is at stake in framing our relation to others as an epistemological question. In doing so, I use Ludwig Wittgenstein’s private language argument and J. L. Austin’s theory of speech acts to show that the film participates in a sustained engagement with the skeptical challenge and makes a crucial intervention in the discussion of race within the context of the kinds of knowledge claims we make, or say we cannot make, about others. Finally, I make a case that the cinematic grammar of the film directs us to reject the framing of racism as an epistemological problem at all, and I suggest what the film is ultimately asking of us.

The Skeptical Challenge to Our Knowledge Claims

Before returning to the fighting brothers in the back room of Sal’s pizzeria, I’d like to take another leap backward in time, to the moment in 1641 when René Descartes decided that he could never be in a position to know anything outside of his own thoughts, effectively condemning us to an ineluctable state of doubt regarding the thoughts or feelings of others.3 This means that our relation to others—for epistemologists, anyway—has been conscripted as an epistemological problem, that is, as a problem of knowledge, rather than as an ontological problem, or a problem of the nature of existence of the world or of others. The skeptical position with regard to what is called the “problem of other minds”—the problem of whether we can, with any degree of certainty, know (or be known to) another—is that since the Other cannot be known with certainty (because there is always the chance of being deceived or wrong about what we think we know), we cannot claim to know anything at all about others. Because I cannot verify that your cry of pain, for example, is genuine and not a pretense, I cannot be said to know that you are in pain. Descartes argued that knowledge has to begin with the mind, with what is private and interior to each person; that the barrier between ourselves and others is unnavigable; and that inference and observation cannot logically be trusted. Clearly, this is an unsatisfactory way of existing, and much of philosophy since Descartes has attempted to find empirical or commonsense data—enough evidence to say, “I do know”—to domesticate the skeptical threat.4 This is likewise unsatisfactory, akin to using calculus to solve a crossword puzzle; it’s an attempt to counter deduction with induction.5 The problem with empirical or inferential data is that they are always subject to doubt; since we could be dreaming, hallucinating, or otherwise deceived, argues the skeptic, we cannot accept this kind of evidence either. In fact, the skeptic requires a standard of evidence that is simply impossible to satisfy.6

What precisely is so troubling about casting our relation to others as an epistemological problem—a problem of a certain kind of “privacy” of the Other (to, or from, me) that is logically unassailable yet might be accessible if we could amass a sufficient body of evidence? The answer, perhaps, is that doing so means, in the first instance, that we are given philosophical grounds to deny the humanity of the Other and, in the second instance, that we can simply ignore the logical force of skepticism, pretending it is not a genuine threat at all or in some cases arguing for a transcendent force such as the existence of God to reassure us (which is Descartes’ end-run strategy). Rejecting both approaches, ordinary language philosophers Wittgenstein, Austin, and Stanley Cavell have taken up the skeptical challenge by examining the ways we use language in our everyday lives.7 It turns out that our “ordinary” (as opposed to philosophical) language includes a large number of statements that are not empirically true or false but instead are descriptive of our experience and so are subject to neither empirical verification nor logical analysis; they are not, in other words, dependent on truth conditions (knowable as either true or false) to be meaningful. These uses of language, or what Wittgenstein calls our “forms of life,”8 are part of what grounds our human community.

Nonetheless, for these philosophers, the threat of skepticism is real; it is urgent; to ignore it is to cut ourselves off from a community of Others as drastically as the skeptic fears we are already inevitably cut off. The skeptic is not so much the enemy as the messenger we would like to blame. The question of how to effectively respond to the message—the claim that we simply cannot know to any degree of certainty anything outside of our own inner states, emotions, or sensations—is inextricable from the question of how we are to engage with the Other at all in the face of the skeptical challenge. For the ordinary language philosopher, this engagement is freighted with an obligation to achieve an ethical intersubjectivity that is not contingent on knowledge claims at all.

Racism as Ignorance

What Do the Right Thing so strikingly illustrates, and situates as tragic, is the epistemological drama of what it would mean to say that we can or cannot know the (in this case racial) Other, and what is at stake in evicting that Other from the possibility of community as a consequence of our knowledge claims. To return to our two Italian American brothers, locked in a wrestler’s hold: what Vito thinks he means in saying “You don’t know” is that his friend Mookie is not really Other, or not so Other; he has gotten to know Mookie, and Mookie is all right (just as Mookie, earlier in the film, defends Vito from his black militant–wannabe friend Buggin’ Out by saying, “Vito’s alright. Vito’s down.”). This is the model of race relations that dominates our cultural myths about what racism is and how it can be overcome: without reference to the origins of racist assumptions, they are generally posited as being located in ignorance. Racism, in other words, is largely conceived as a class of epistemic failure; that is, it is a failure to know. We could say that racism is treated as a special class of the “problem of other minds.”9

In the United States, the African American has been broadly constituted as an immitigable and unknowable Other in relation to the white Self, which is constituted as central and universal.10 The mirror image of this claim, presented as its antidote, is that with the production of sufficient knowledge, racism (i.e., ignorance) could be overturned. Vito’s assertion that Pino doesn’t know (because he hasn’t gotten to know Mookie the way Vito has) moves toward precisely the model of epistemic failure or success that the film dramatizes with regard to race.

The model of racism and its overturning endorsed by Vito has tremendous narrative power: it is clear; it is dramatic; it involves precisely the kind of transformative experience that, in classical theater, allows for audience catharsis; but above all, it is simple. What this model likewise supports is the overwhelmingly reinforced notion that racism can be defined, understood, and confronted solely on the level of personal bigotry. That is, such a model conveniently ignores the larger spectacle of a society grounded in white privilege and whose cultural, economic, social, and political institutions invisibly perpetuate “whiteness” as a normative state.11 Furthermore, this model supports the equally popular notion of personal (rather than institutional) responsibility for success, and the corollary notion that the United States functions as a meritocracy, a system in which anyone who works hard enough (as Sal, who built his pizzeria with his “own two hands,” does) will succeed according to their worth.

Do the Right Thing, however, demonstrates that claims to knowing the Other are insufficient to overcome racism precisely because racism is still built into our social, political, and economic institutions such as education, banking, housing, and even family systems—institutions that allow Sal, for example, “the time and strength—that Mookie has not—to forge ties of warmth and integrity with his sons. [Sal] has had the economic fortune—that Da Mayor [Ossie Davis] has not—to be able to be in the position to hand Da Mayor the broom to sweep his sidewalks with discretion and dignity, and to buy photos he does not want from the neighborhood crazy.”12 Sal recognizes neither his own privilege nor his customers’ lack of it; he simply sees himself as a nurturer of the children who, he says proudly, “grew up on my pizza.” Sal’s framing of himself as the father figure of the neighborhood kids does not stop him from picking up a baseball bat—not because he has been physically threatened but because Buggin’ Out questions his sovereign right to exclude photographs of African Americans from the pizzeria’s “Wall of Fame.” Sal’s disproportionate and violent reaction to this insubordination signals his unquestioning investment in his own (institutionally sanctioned) authority.

I suspect that part of the media’s negative—even hostile—reception of Do the Right Thing can be traced to its refusal to participate in the Hollywood version of the overcoming of differences through personal knowledge of a specific representative of the Other who “proves” that he or she is both knowable and, typically, committed to values consistent with white, middle-class notions of virtue. This suggests that white audiences, at least, are more comfortable with this epistemological model because it does not challenge them to address racism at a societal level but only at the level of the individual, who can always be recuperated through sufficient knowledge.13 The burden of proof, either way, appears to be on the African American. Do the Right Thing was attacked by many critics in ways that suggest that Lee’s film used complex strategies to unpack race problems from a perspective that made audiences and reviewers deeply uncomfortable.

Wittgenstein’s Private Language Argument

Before turning to what the film itself does on a cinematic and narrative level to elicit this level of discomfort, I first want to sketch what is at stake in linking the idea of racism to epistemological claims regarding the knowledge of other minds. One way Wittgenstein has dramatized the skeptical challenge is through the private language argument.14 Wittgenstein asks us to imagine a language that is intelligible to only one person, a language that no one else can know or learn and that refers only to things the single user of that language can know. He describes the language like this: “The individual words of this language are to refer to what can only be known to the...

Table of contents

- Cover

- Half title

- Title

- Copyright

- Contents

- Preface

- I. Justice, Value, and the Nature of Evil

- II. Race, Sexuality, and Community

- III. Time, the Subject, and Transcendence

- List of Contributors

- Index